What's the first thing that comes to mind when you think of a CEO of a Fortune 500 company? How about when you think of a Poet Laureate? Chances are, based on past experience, you hold contrasting views of the two. It’s these types of preconceptions a new course helped dispel.

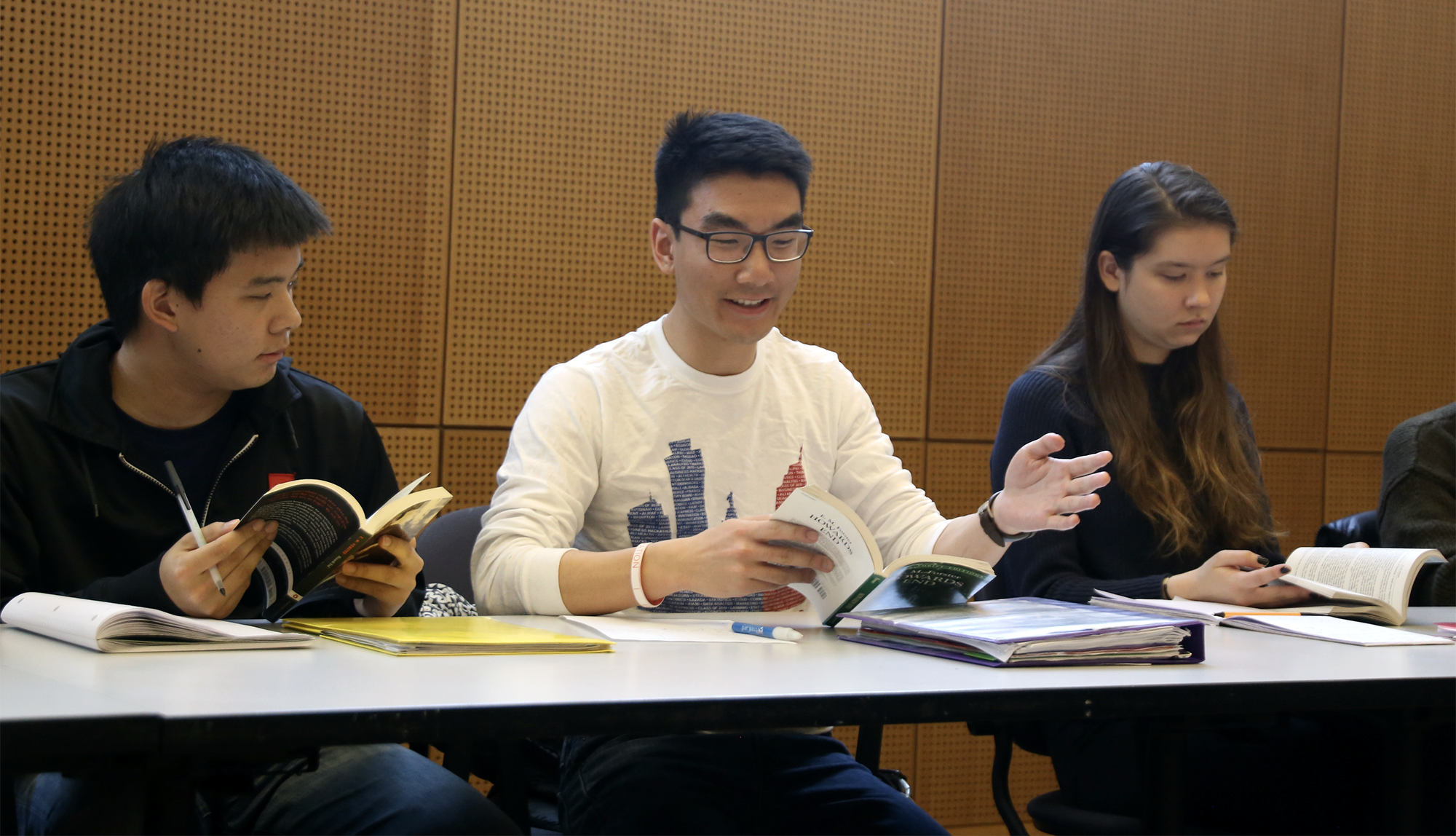

Literature and Business, taught by Vartan Gregorian Professor of English and Department Chair Jed Esty, brought together students from the College of Arts and Sciences and the Wharton School. The course was designed to examine the ways in which the humanities and business intersect in our world today. Through a careful examination of literature that explores representations of corporate and entrepreneurial life from the early-mid-1800s to the present, as well as thoughtful discussions on the emotional, moral, and social life of women and men working in business, students were given the opportunity to expand their definitions of the two divergent academic worlds and career paths.

“I taught some specialized seminars—one called Victorian Action Heroes and another called Literature and Dictatorship—and they were starting to draw in students from pre-med, Wharton, engineering, and nursing,” says Esty, whose department has also introduced courses in Literature and Law and Literature and Medicine. “Students were enthusiastic about our developing more courses in English organized around other professions.”

Esty—whose brother, a finance professor, has long been a source for kitchen table discussion about the different worlds of the humanities and business education—says the dynamic extends to the social interactions of students on campus. “There's a friendly rivalry that exists between Wharton and the College—they mix socially, but there’s a persistent feeling that they're driving towards different goals,” he says. “The cartoon versions of what it means to be an English major or a finance student are exacerbated sometimes by the business versus liberal arts tension at Penn.”

English major Mariah Macias, C’17, says it surprised her just how many Wharton students signed up for the class. “We were responsible for reading the first 150 pages of a Dickens novel prior to the first class—which would, in normal circumstances, dissuade non-English majors from continuing with the course,” she says. “But the Wharton students contributed just as much, and with as much insight, as senior English majors.”

Esty worked to expose preconceptions early on. “We had a very funny conversation at the outset listing stereotypes about businessmen,” he says. “The very first thing someone brought up was this American Psycho movie version of the businessman, which suggests that there's something depraved happening on Wall Street. In reality, I find that Wharton students often have a very strong sense of social mission, not just associated with their volunteer life, but associated with the idea that being businesspeople is a way of producing social value.”

The literary curriculum for the course followed a narrative journey through the stages in the life of the corporation—from family business to Fortune 500 company—and investigated what it means to be either a part of them, or affected by them. Students started with Dickens’ Dombey and Son, from the mid-19th century, which examines the risks of eroding trust in family business. The class also read Howards End, which represents an early history of the competitive relationship between the professional and managerial classes.

When the reading arrived at representations of the mid-20th century business person, things got more complicated, Esty says. “Arthur Miller's protagonist in Death of a Salesman—the figure of an aged and frustrated nylon merchant—has evolved in the age of Google, where you have creative young people riding slides down into their pods and lounges. The clichéd, pinstriped American corporate man stereotype is increasingly a part of history.”

Isaac Nilsson, W’18, says that hearing the English majors’ in-depth analysis of the writings proved valuable. “The Wharton students contributed with a more hands-on perspective,” he says. “Professor Esty is really good at finding a balance between abstract and focused discussions.”

The literature and class discussions often led to poignant philosophical debates. “We explored the notion of professional virtue and what it means to be inauthentic in the workplace in order to get what you want,” says Esty. “The Dickensian story of Scrooge, for instance, highlights a prototypical myth of the businessman, which is that money eats away at your soul and that love of money displaces love of humanity.”

Macias says that she and her classmates were aware of each other’s biases and acknowledge that they all approached discussions and materials based on their own experiences and external influences. “My favorite moments in this class were when the majority agreed on one point or belief about the text, and then someone else contradicted them entirely,” she says.

Sarah Samuels, C’17, says the dynamic created a unique camaraderie. “By the second week, one of my classmates had even created a class Facebook page,” she says, “where people posted supportive messages, funny memes, or articles related to our reading.”

Esty says in the future that he’d like to find new ways to explore the intersection of academic tracks. “We’re now thinking of trying yet another new class, Literature and Code, which might bring computer science and engineering students to our curriculum and into the mix with our majors and other liberal arts types.”