The Many Sources of the Nile

In a recent artistic collaboration, Alexis Rider, GR’22, unsettles long-standing narratives about the Nile River and its exploration.

Stretching over 6,600 kilometers, or 4,100 miles, the Nile is the longest river in the world. It flows from the rivers around Lake Victoria, near Uganda, northward into the Mediterranean Sea. For thousands of years, beginning with records from ancient Egypt, the Nile’s history has been intertwined with human history. Many of these accounts marvel at its mysteries, explains Alexis Rider, who completed her Ph.D. in the history and sociology of science this past May. Others, like those of British explorer Sir Richard Burton, reveal frustration with the river’s unknowability. In the 19th century, Burton and his contemporaries became obsessed with finding the source of the Nile, with settling the question—and the river—once and for all.

In the fall of 2021, Rider and Himali Singh Soin, an artist and poet, began putting together an interactive installation of images and texts that would unsettle this colonial history. The exhibition, Brow of a God/Jaw of a Devil: Unsettling the Source of the Nile, disentangles the Nile from human explorations of it by foregrounding the river and its landscape. The exhibition opened at the Orleans House Gallery in London on November 16, 2021, welcoming nearly 150 guests with a special performance by noted British violinist Blaize Henry.

Rider and Singh Soin conceived their exhibition in response to the Orleans House’s call for artistic investigations of its collection of Burton’s personal effects. The gallery, which is located on the edge of the Thames River, near Burton’s burial site, hosts an archive of Burton’s paintings, photographs, and books. With their shared interests in the non-human elements of environmental science and history, Rider explains, she and Singh Soin decided to interrogate Burton’s search for the Nile’s source.

“We were specifically drawn to the idea of thinking with the river and thinking about the river,” says Rider. “It seemed like a really interesting way to challenge and bring to the fore ideas of both archives and natural spaces—the ways that rivers, and the Nile in particular, obfuscates and keeps some of the information and its own material history quite well hidden.”

For Rider and Singh Soin, the archive reflects the river in its fluidity and unknowability. “Everything that you find in an archive, you are reinterpreting or trying to fill in spaces and emptiness,” Rider says, explaining that they wanted the exhibition to emphasize the unsettled nature of both the Nile and archival sources.

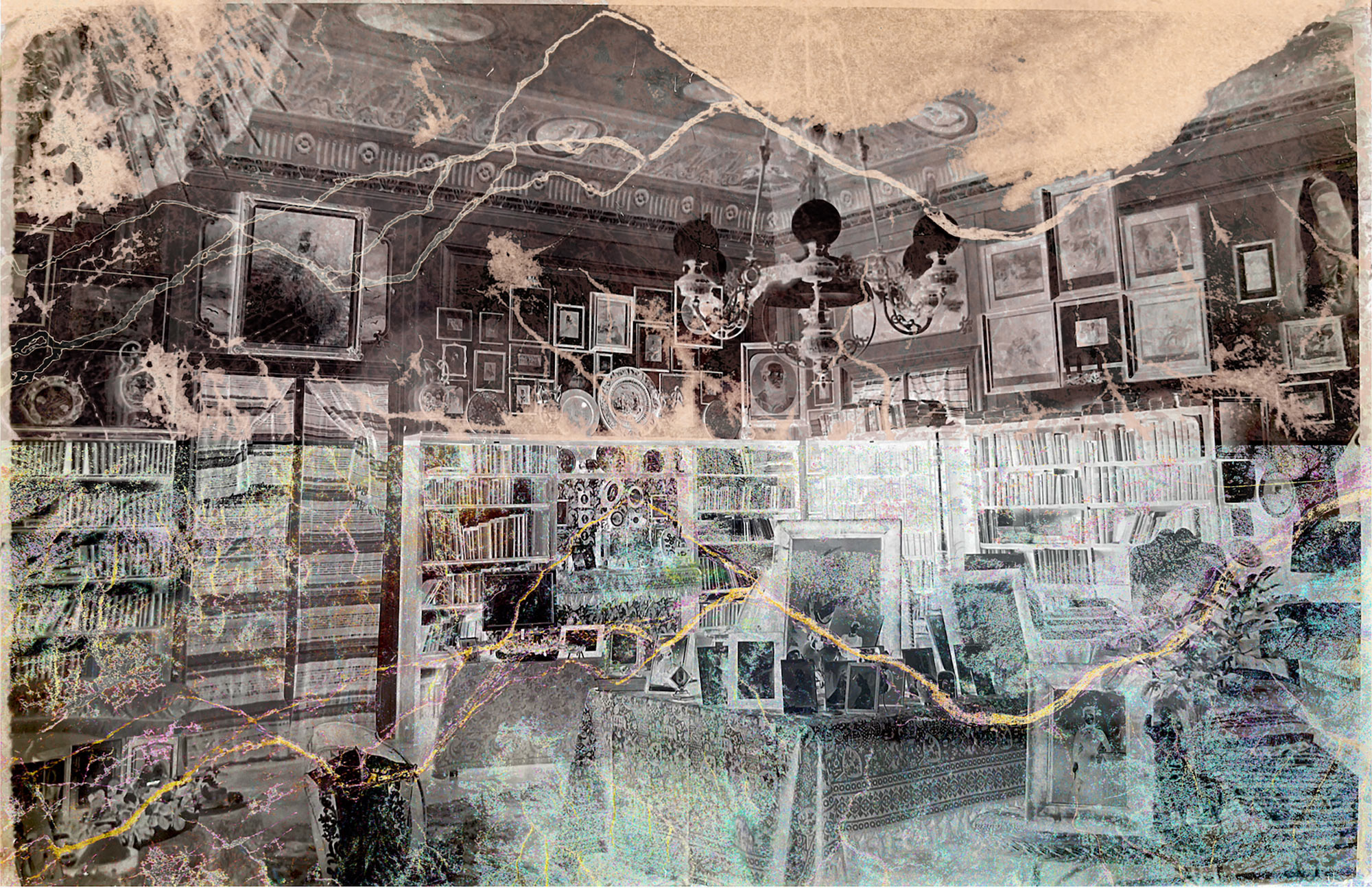

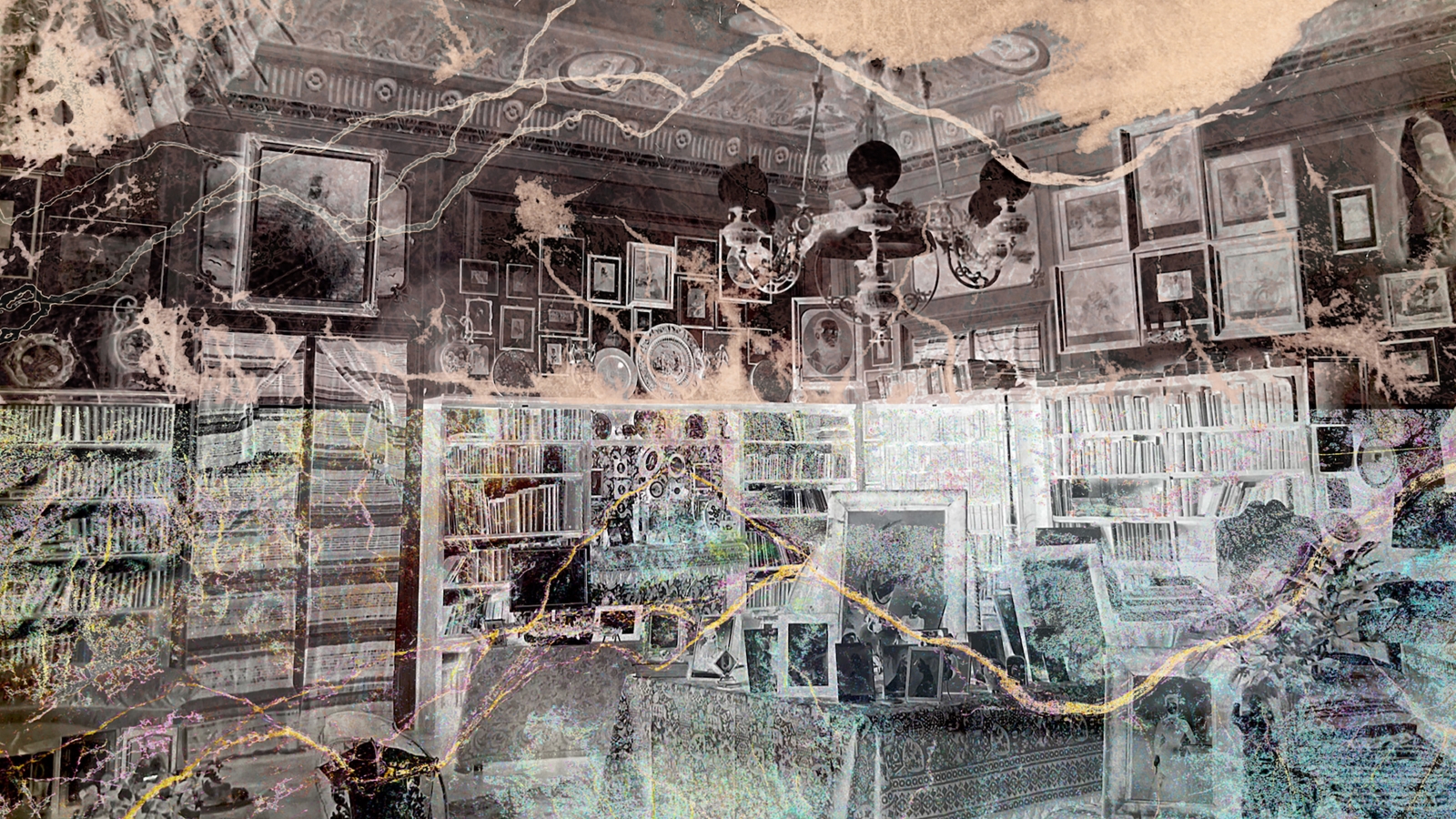

The images Singh Soin gathered for the exhibit include negatives of photographs from the gallery’s Burton Collection presented on backlit glass plates. Some are overlaid onto images from other sources, including ancient Egyptian maps of the Nile, 18th- and 19th-century sketches of the Lunae Montes, a mythical mountain range once imagined to be the source of the Nile, and NASA images of the Sudd region in Sudan, which obstructed efforts to find the river’s source. These ghostly inversions allowed Singh Soin and Rider to work with Burton’s archival materials, while also minimizing his presence, Rider explains.

“We wanted it to all feel kind of haunted and like you could spend a lot of time looking at the images to try and pull out what each layer was,” says Rider. The images are hung on wires alongside 16 vignettes, inspired by different accounts of the Nile, that Rider wrote. Visitors to the exhibition could move the images and texts around, reordering them to create new narratives and perspectives on the Nile. “There was no rigidity to either the ways that the images and the writing interacted or the way the viewer interacted with the space, so it was playing with this idea of how pasts are kind of constructed and understood and remembered—and how the viewer has an important role in this process,” Rider says.

Rider’s research for the exhibition took her in several directions, from contemporary scientific studies that locate the Nile’s source in the earth’s mantle to ancient Egyptian flood records. The subject of the exhibition departs from Rider’s doctoral research, which examines what ice can reveal about the deep past and the future of the planet. But the goal of centering an environmental phenomenon felt familiar, she says, “because we were trying to take a non-human actor and really elevate that and think about it as kind of a historical figure.”

While Brow of a God/Jaw of a Devil concluded on March 13, 2022, Rider says she and Singh Soin designed the exhibit to exist beyond the space of the Orleans House. As more than a history lesson, she explains, it serves as an example of engaging the public in environmental humanities. “It’s trying to give people a way of responding to and thinking about their place within the environmental crisis and the changing environment that we exist in today,” Rider says. Stateside, the exhibit can be viewed this summer as part of Fluid Matters, Grounded Bodies: Decolonizing Ecological Encounters, a feminist, queer, and trans ecocriticisms exhibition at New York University’s Gallatin Galleries.