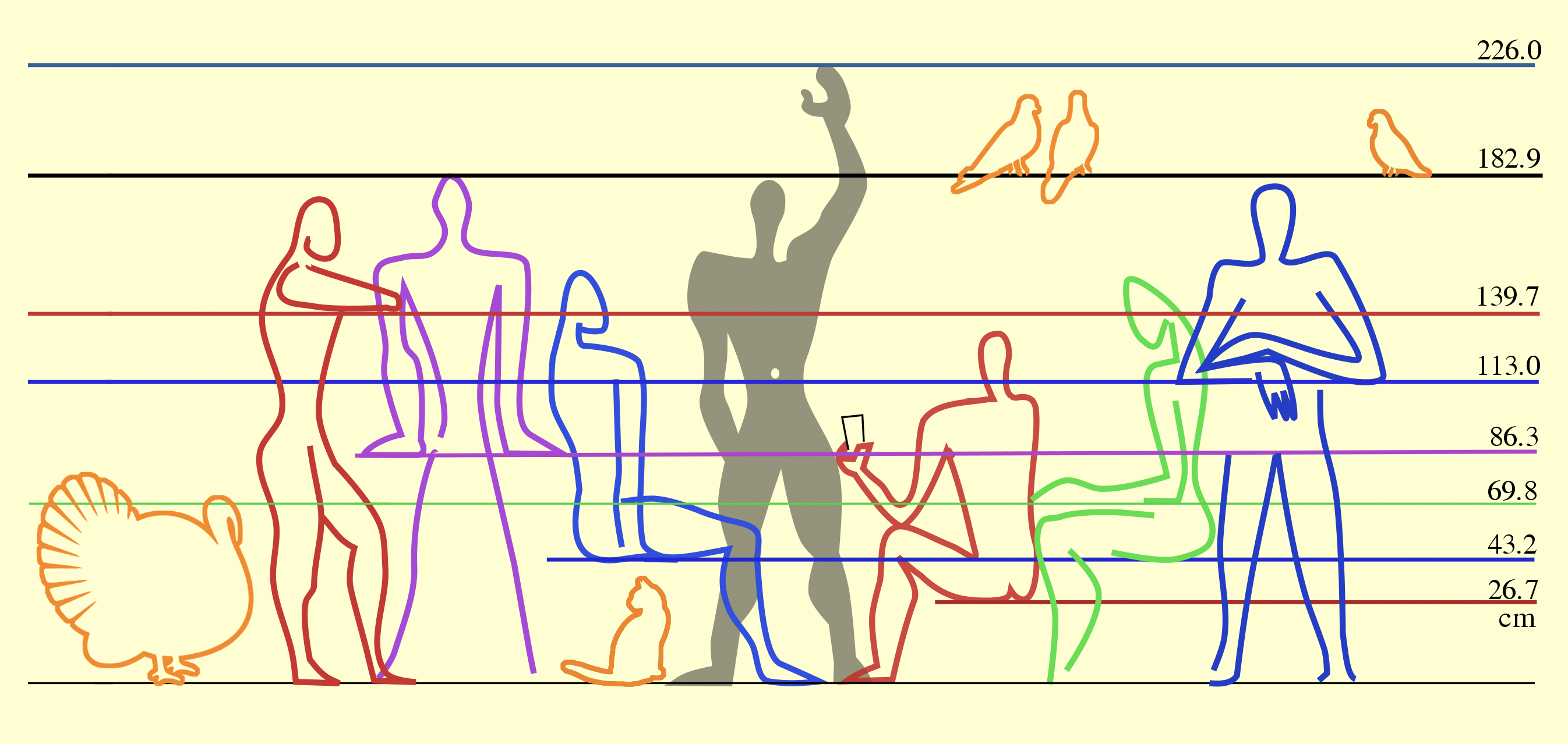

“Wildlife habitat” may not be the first descriptor many would use for Philadelphia, but in fact the city is filled with fauna. Besides the ubiquitous squirrels and pigeons, it’s home to other birds, cats, rabbits, hedgehogs, possums, turtles, rats, mice, and insects. Add to that a few urban farms, residents’ pets, and, recently, more unusual critters, like foxes and coyotes. Is it possible to better cohabit with these non-human residents of the city?

Undergraduate and graduate students in the course Space/Power/Species have dived into the history, philosophy, and social science of human-animal relationships, using what they’ve learned to design projects that create space for animals in a people-centered city. Their work will be on display in the pop-up exhibition, The Multispecies Metropolis, Thursday, May 4, from 4-7 p.m. in the Dean’s Alley of Meyerson Hall.

“Animals are such an important part of human cultural life,” says Richard Fadok, a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wolf Humanities Center, who teaches the course. “They figure in our stories and our speech. We use so many animalistic metaphors. We also rely on animals for food, clothing, medicine, and other products, not to mention labor, knowledge, entertainment, and companionship.”

At the same time, says Fadok, our relationship to animals is changing, and we can read that change in the way we design cities. “Our cityscape looks very different from 150 years ago. We used to see more animals within urban areas, both wildlife and domesticated animals. Dogs roamed the streets. Our vehicles were horse-driven. Cows grazed in common areas. Farms with pigs were interdigitated with homes.”

Changes in economy, technology, and urbanization pushed many of these animals out of the city, but now some wildlife are making a bit of a comeback, Fadok says. “We’ve actually seen total transformations in urban ecologies over the last three decades.” That’s partially due to development that has reached into animal habitats and to climate change, but Fadok says that changes in urban form, like the greening of cities and different regulatory policies, have also made metropolitan life more appealing for certain species.

Humans and Other Animals

Fadok is an anthropologist of design. He wrote his doctoral thesis on human-animal relations in biomimicry, in which designers, engineers, and others look to the biological world for inspiration. An article about the work of Joyce Hwang, who creates habitations for urban wildlife like bats and bees, flipped that idea for him. “Designers like Hwang study animals not just to appropriate design for human use, but to reciprocate.” he says. “They study the design principles of how a bird builds its nest in order to create new types of nests that would welcome birds into the built environment.” Fadok’s research on design for animals asks how architects’ understandings of space change as they treat animals as users of the built environment.

The Space/Power/Species class grew out of that new interest. The course is multidisciplinary in both format and makeup. It’s cross-listed with design, anthropology, and science, technology, and society. Half the students are College undergraduates from a variety of disciplines and half are master’s students in the Stuart Weitzman School of Design. To get students with such diverse experience on the same page, Fadok wrote guides on how to read academic literature, write scholarly essays, practice design and curation, conduct field work, and critique each other’s work.

The class itself is a mix of seminar-style reading and discussion and a studio component that joins ethnographic fieldwork of a local architectural site with speculative design exercises that prompted the students to re-imagine the site to be more animal-inclusive. “We did a lot of reading and a lot of learning about theory, about different ways of approaching animals, and then the human relationship in the urban space and beyond,” says Maggie Song, C’25, from Baltimore. “That primed us for the second half, which was finding a site and an animal, observing them over time, and then trying to apply the knowledge and our thoughts that stemmed from all the theories we’ve learned into creating a solution.”

The class also took field trips to the Slought Foundation, the Penn Museum, and the Spruce Hill Bird Sanctuary. An architectural historian, a landscape architect, an architect, and an anthropologist visited to offer critiques of the students’ projects. The students have also benefitted from their own mix of experience, what Fadok describes as a “cross-fertilization” between backgrounds.

“The master’s students shared their skills, like doing models and schematics,” says Song. “And intellectually, we’re able to have very good conversations.”.

Space for the Non-Human

Song is double-majoring in design and science, technology, and society. She was drawn to the class by its topic and by Fadok’s interdisciplinary approach, “which provided theory and practical elements, and then also an opportunity for a creative exploration about how to solve these problems in our own way.”

Ashley Ray, C’24, a biological anthropology major from Philadelphia, took the course to fulfil a requirement and because of an archeological project they’re researching that involves insect pests. “A large part of my research was considering the dynamics of people living in a house filled with insects. And this course was presented to me as one that explored the complexities that come with humans and animals occupying the same space.”

Much like Fadok, Ray was affected by the work of artist Joyce Hwang. “She’s done a lot with this idea of increasing animal visibility in areas where certain species that are considered vermin are typically ignored or pushed to the wayside,” they say. “Her whole method is to expose people to these animals and in that sense build up a tolerance, I suppose, to their existence. And so, she’s created these insane structures as a method of increasing the visibility of these animals that might be considered gross or ugly or disturbing. I found that very moving.”

It’s a combination of viewing these animals in their natural landscape, where they’re unbothered, humans are unbothered, and also educating the public about how these animals fit into the wider ecosystem, how they live.

Ray’s group project, which involves squirrels in the Geology Garden behind Hayden Hall, was influenced by Hwang’s approach and their own work at the Philadelphia Zoo. The group’s architectural intervention imposes signage and animal structures. Like the overhead catwalks at the Zoo, the structures separate humans and animals spatially, but increase the animals’ visibility, “to expose them to the human gaze, to be like, ‘Look at them,’” says Ray. “It’s a combination of viewing these animals in their natural landscape, where they’re unbothered, humans are unbothered, and also educating the public about how these animals fit into the wider ecosystem, how they live.”

Song’s group project site is Cira Green, a rooftop park near the Schuylkill. Its location and use imposed limits, from the constrained physical space to the owners’ rules and goals to human social norms. Each team member took a different perspective, including accessibility for humans, the relationship of wild birds with the people there, and how the space is used throughout the year. Song looked at the physical structure and how that affects use by both humans and animals. “Our end goal as a group is to synthesize these different perspectives and offer a solution,” she says.

Transformations

Fadok says he’s been consistently surprised by his students’ innovation, “how they have synthesized different readings in ways that I probably would’ve never thought of.”

Both Song and Ray found looking through a non-human lens challenging and transformative. “In our current world, we tend to hold a very anthropocentric view of the world and our place in it,” says Song. This class “just shows how valuable it is to take a step back from that, to see ourselves also as beings in the environment and how the changing landscape has affected both us and others within it.”

Ray is also looking at the world differently, and says they’ve felt inspired by the process. “I’m thinking of creating an article, based on my research but incorporating the discussion of animal agency and how people are shaping their identity through their relationships with animals.”

Fadok will also be writing; his commentary on the course will be published in the journal Teaching and Learning Anthropology. His goals for this new class went beyond teaching theories about animals in the built environment and seeing students put those to work. “One thing I’ve experienced, taking different kinds of courses on the environment, was an overwhelming sense of dread or anxiety or nihilism. There is this sense that we’ve ruined the planet and that there’s nothing that we can do about it. And while I don’t think that solutions are easy by any means, I wanted to instill an idea that through empirical research and design practice we can start to address some of these issues in a really practical and hands-on way. So, to put it simply, what I wanted students to get out of it was a feeling of hope. I wanted them to get an understanding that these issues, while complex, are not entirely intractable.”

For more on The Multispecies Metropolis exhibition, click here.