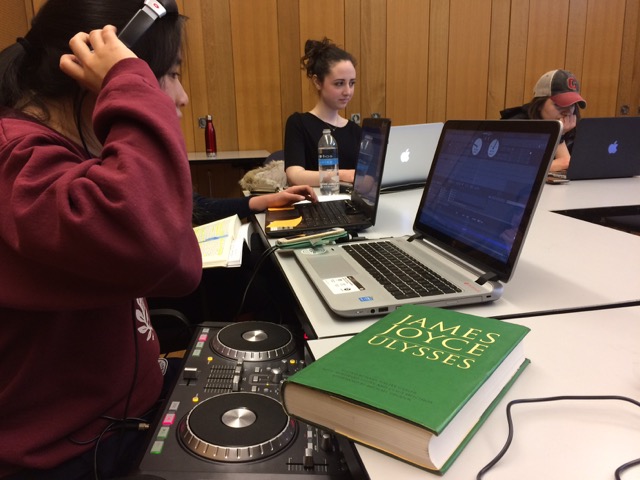

Professor of English Paul Saint-Amour requires students to read James Joyce's Ulysses, that behemoth of Modernist literature. But, he says, his class is also an “invitation to play.”

Saint-Amour teaches Joyce's Ulysses: Making Readings alongside artist Robert Berry, a cartoonist and illustrator known for his work in Joyce studies. The course is part of an English department initiative called Critical-Creative Approaches to Literature. In the Ulysses course and others like it, students read literary texts and embark on creative projects informed by what they’ve read. “Creation in-kind can be a form of analysis, even critique,” Saint-Amour says, and students must become deeply familiar with Ulysses—its plot and characters, but also its structure, its cultural and literary context, and its use of language—before they begin their own creative projects.

Ulysses is Joyce’s retelling of Homer’s Odyssey, set entirely on June 16, 1904, in Dublin. It follows protagonist Leopold Bloom across the city and recounts the dizzying array of people he encounters, complete with what Berry describes as “character dialogue, interior monologue, and third-person narration with sounds and interruptions of a busy, modern city.” The novel, whose chapters correspond with Homeric episodes, is notorious for its difficulty. That difficulty is part of what has drawn readers to Ulysses since its publication in 1922. It is also what makes it ripe for interpretation, adaptation and celebration. Every year on June 16, fans of the novel celebrate it with Bloomsday, named for Leopold Bloom. Bloomsday is a festive affair that varies from city to city but generally involves readings, musical performances, and libations.

Berry recognized that while Ulysses is challenging, it is also funny, often dirty, and always appreciative of the rhythms and routines of ordinary people's lives. It may be considered highbrow literature now, but the book was put on trial in the United States on charges of obscenity and was banned in the United Kingdom. Interested readers had to seek smuggled copies. Berry wanted to reclaim some of the novel’s everyday appeal, so he set out to adapt Ulysses’ 700+ pages into a graphic novel, episode by episode. His ongoing adaptation, ULYSSES “seen,” (pictured above) provides him with a new way of relating to the novel and makes it accessible for readers who might otherwise be intimidated or dismissive of the novel’s relevance.

Saint-Amour and Berry want their students to approach Ulysses as “slow literature.” It demands to be read carefully, for students to spend time with it, and to consider various interpretations. “We tell students that reading the novel is a lot like being dropped in the middle of a foreign and modern city,” Berry says. “One in which you speak much, though not all, of the language; recognize some, though few, of the people or their history; and understand many, though certainly not all, of the jokes. Half the fun is learning how to get around and how much more there is to see.”

The characters and themes in Ulysses are so vast that, as Saint-Amour says, “There is a perch for everyone.” When students in the course found their perches, they formed groups and began thinking about how creative projects could offer new ways of understanding and relating to the text.

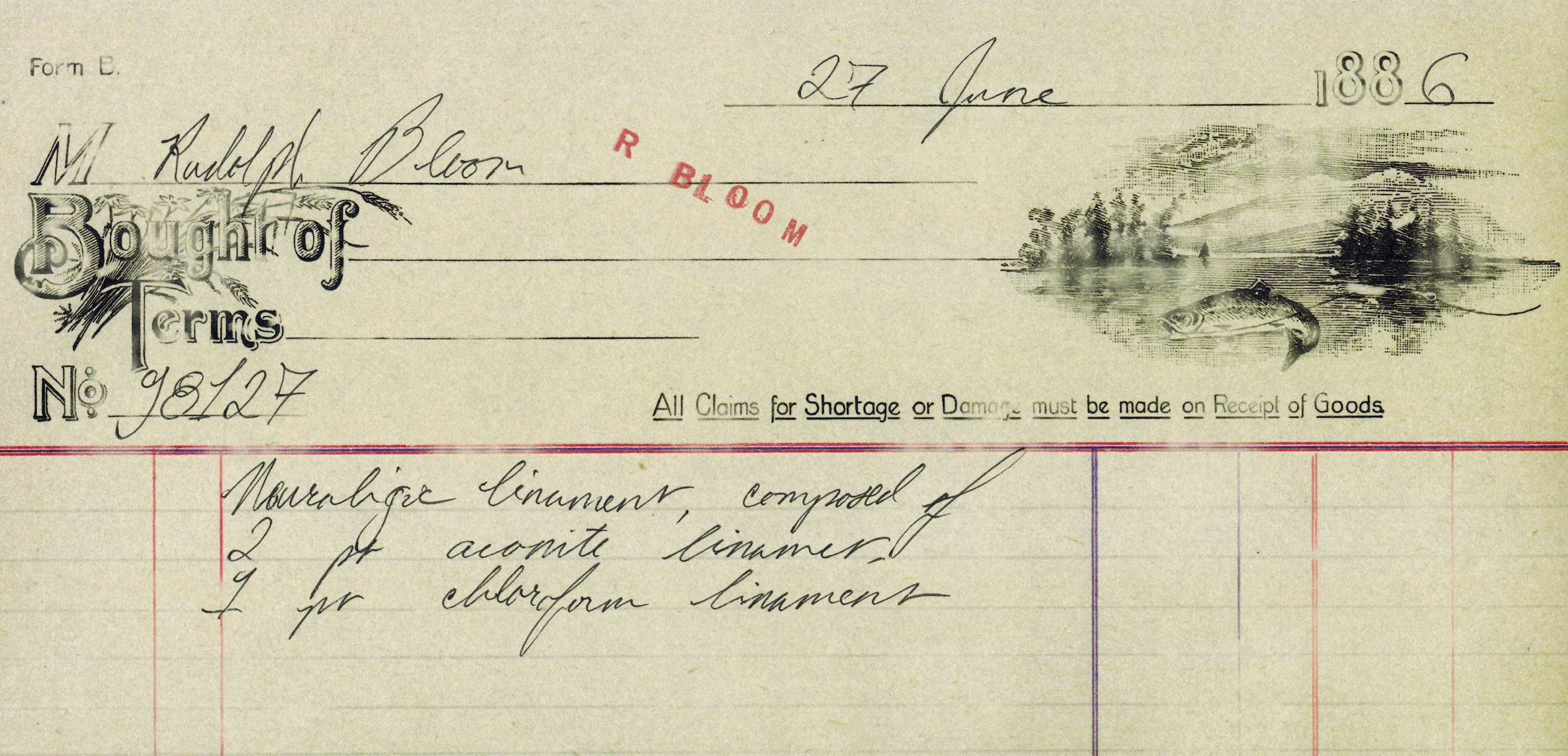

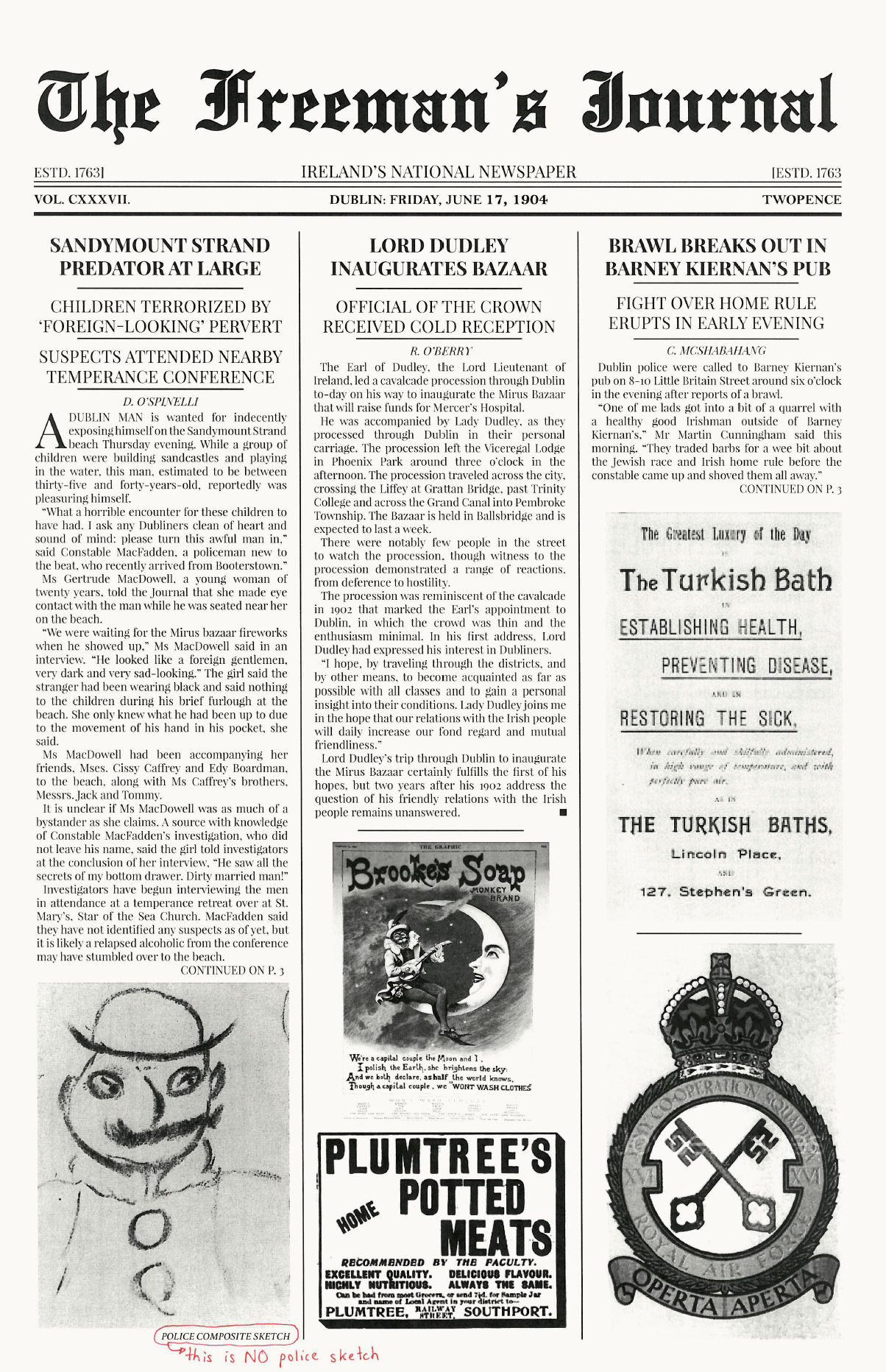

The resulting projects included original musical compositions based on the Proteus, Sirens, and Penelope episodes, and a digital humanities project that presents an original, apocryphal episode using web technology to display the simultaneous, individual experiences of two characters in the scene. A group of students, all writers for the Daily Pennsylvanian student paper, wrote and designed a newspaper issue for the day after the events of the book, complete with police reports about the characters’ crimes, a political editorial by a nationalist character, advertisements for events and products discussed in the novel, and editor's notes. Another group created a scrapbook of the ephemera in the novel, writing and designing letters, journal entries, tickets, and receipts.

Saint-Amour hopes that through these projects, students will have moved past the novel’s reputation for difficulty and connected to it in a personal way. Ulysses offers much to think about when it comes to literary and visual representations, censorship, history, politics, gender and sexuality, and the conventions of literary and visual representation. Set in 1904 but written between 1914 and 1921, it grapples with the accelerating modernity of those years. “You can feel the early 20th century vibrating in its pages,” Saint-Amour says. As it nears its centenary, Ulysses continues to offer a different experience to every reader and rewards to those who rise to its challenges.

Saint-Amour serves on the Community Partners group for Philadelphia’s Bloomsday celebration at The Rosenbach.