Let the People Go?

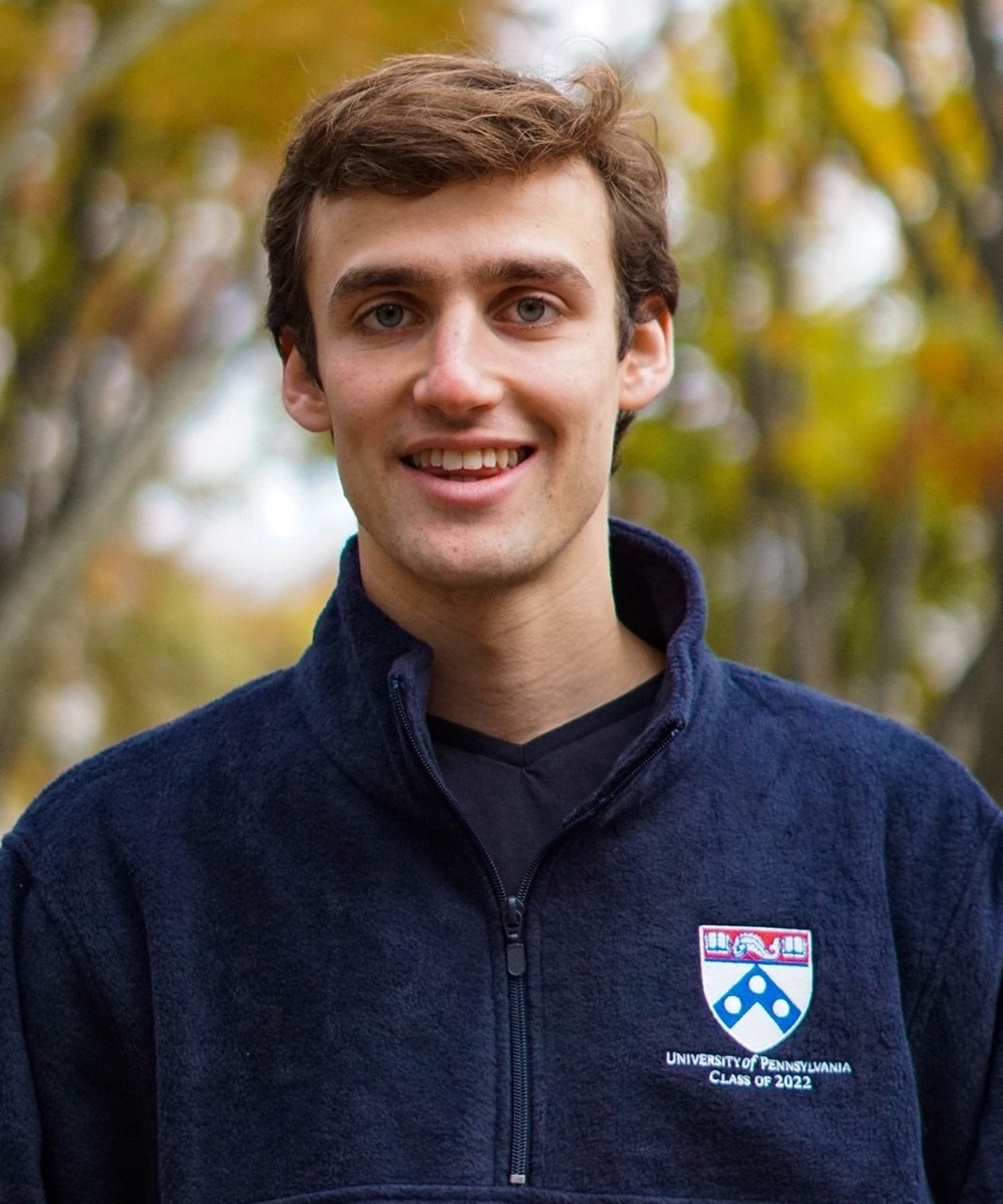

Samuel Strickberger, C’22, investigates Jewish Orthodox reactions to slavery in antebellum America.

Between 1848 and the end of the Civil War, the population of Jewish people in the United States grew from 50,000 to 150,000. What did these migrants, with their own history of enslavement, think of the slavery in their new country? Samuel Strickberger, C’22, set out to answer that question in his history honors thesis, “Theological Crisis: The Jewish Orthodox Race-Based Slavery Debates, 1848-1861.”

The topic is personal for Strickberger, who describes it as “the confluence of a lot of different things that have invigorated me since high school.” He was raised in a Jewish household outside Washington, D.C., and took a gap year between high school and college to study at the Shalom Hartman Institute, a pluralistic think tank in Jerusalem. He’s also interested in politics; he’s been president of his class since sophomore year and is minoring in survey research and data analytics through the Penn Program on Opinion Research and Election Studies (PORES).

“I grew up in a household where a major aspect of being Jewish meant feeling a sense of obligation to stand up when things are not just,” says Strickberger. “At the same time, I recognize that religion does not always play that role, that theologies can sometimes promote insularity or discrimination.”

During his junior year, Strickberger did an independent study with Sarah Barringer Gordon, Arlin M. Adams Professor of Constitutional Law and Professor of History, which helped sharpen his thesis topic. He spent the summer looking at primary sources, including rabbinical sermons, responsa, and newspaper articles, at the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at Penn and the Center for Jewish History in New York. The research was funded by a Wolf Humanities Center Undergraduate Research Fellowship, a Philip E. Goldfein Scholarship in Jewish Studies, and a College Alumni Society Undergraduate Research Grant. “It was amazing to open up a book from the 1850s and go through it with my own hands,” he says.

1848 marked the beginning of a wave of migration to the United States from European countries like Germany, which had recently experienced failed revolutions. This wave included 100,000 Jews, and Strickberger says it meant “a huge reorganizing of Jewish life in America.”

The migrants arrived in a nation embroiled in debates about the enslavement of millions of Black people, the era’s most pressing moral issue. The Jewish community was also facing a looming religious crisis. The European Enlightenment and the Haskalah, Jewish Enlightenment, facilitated a 19th-century schism in which the Orthodox and Reform movements emerged. The Haskalah was an intellectual movement that “sought to integrate the ideas and values of the Enlightenment, principally increased reliance on reason and adaptation to modernity, into Judaism’s fabric,” Strickberger explains. Beyond all this, the new migrants were simply trying to assimilate and be accepted into America’s broader society. “How do religious leaders deal with all these competing interests?” asks Strickberger. “How do certain theologies motivate people to value or focus on one at the expense of others? Or to focus on all of them concurrently?”

Although being in America gave Jews more political freedom, they were still a new immigrant community. “The Jewish community was in a precarious situation,” says Strickberger. “They were trying to assimilate and stay below the radar. Silence was a much easier option than advocacy.” Other German immigrant communities, he says, also tried to remain silent about the issue of slavery: “Most individuals were trying to fit in and become American.”

As the Civil War grew closer, clergymen of all faiths were pressed more on the issue. One trend that Strickberger discovered was that some traditional rabbis seemed to categorize and react to the abolitionist movement in a similar fashion as they did to the Reform Movement. “They did not want progressive or modern forces to misuse the Bible. But in doing so, these individuals ultimately defended inhumane bondage in the name of the Bible,” he says. “On the other hand, rabbis who were anti-slavery were able to weigh multiple values, human dignity with traditional observance—their approach was more holistic.”

“I think some of the most productive conversations can come from our discussions, because seeing people my age work through producing academic work is so interesting.”

“There are many lessons from Jewish texts—like ‘Justice, justice, you shall pursue’—and Jewish history that remind us of the importance of standing up and what happens when people do not,” says Strickberger. “It is not always easy to witness a history where individuals who share aspects of my religious worldview also advanced a position so obviously wrong. As a Jewish person and a religious person, I wanted to see much more advocacy within the Orthodox community, despite the real and complex obstacles, such as being part of an immigrant community and dealing with fundamental shifts in religious life.”

Strickberger is a Wolf Humanities Center Undergraduate Fellow in a year when the center is focusing on migration. Wolf fellows all take part in bi-weekly sessions to discuss their work. “I think some of the most productive conversations can come from our discussions, because seeing people my age work through producing academic work is so interesting,” he says. “Workshopping peers’ pieces helps me better understand how I can improve my own.”

Advised by Gordon, Strickberger completed his thesis in December as part of the History Honors Thesis Program, a two-semester course taught by Kathy Peiss, the Roy F. and Jeannette P. Nichols Professor of American History.