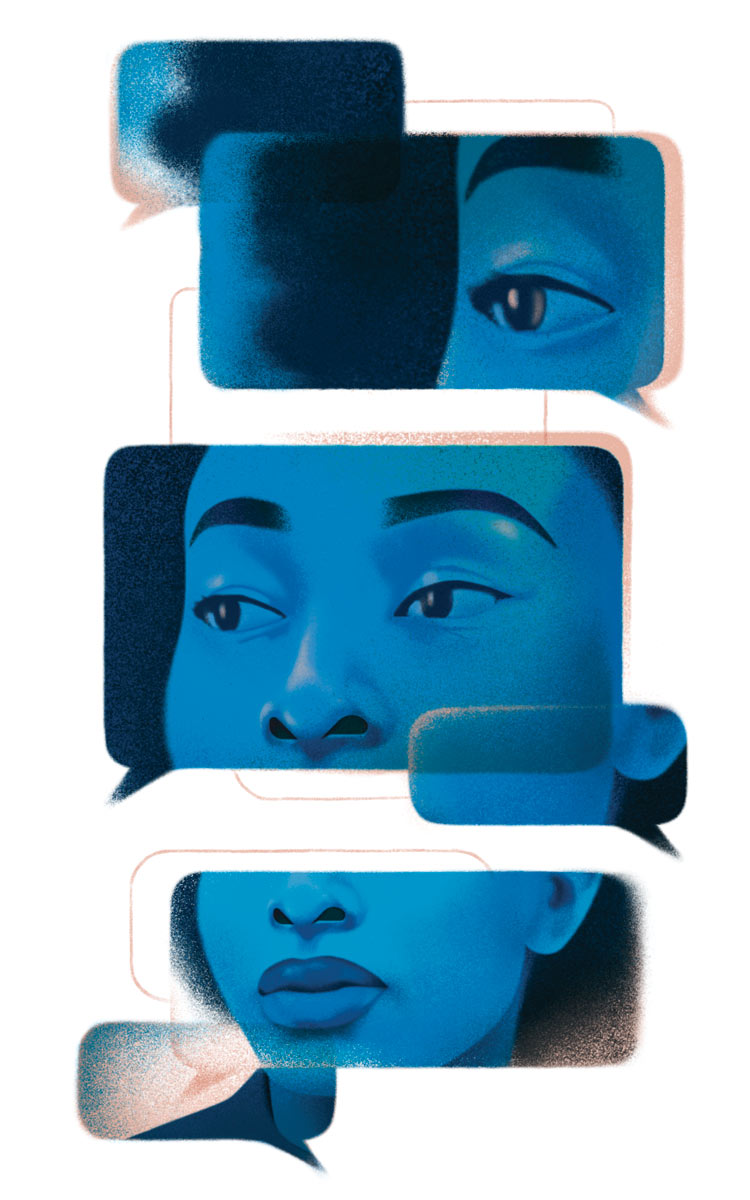

Same-race friendships on college campuses can be sources of support and help build a sense of belonging. However, sociologists Sherelle Ferguson, GR’21, and Annette Lareau, Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Professor in the Social Sciences, have found that class differences can create tensions within these relationships.

In a recent piece published in Socius, titled, “Hostile Ignorance, Class, and Same-Race Friendships: Perspectives of Working-Class College Students,” Ferguson and Lareau describe findings from in-depth interviews with working-class, first-generation students at two private universities. These students describe micro-aggressions in interactions with their more affluent peers around everyday concerns like hair, academics, and money.

“Being from a lower-class background is still a stigmatized identity on many college campuses,” says Ferguson, who earned her doctorate in sociology from Penn last year, is currently a postdoctoral fellow at Temple University College of Education and Human Development, and will be an assistant professor of sociology at UC Irvine this upcoming fall. “Prior literature has discussed the alienation that upwardly mobile students feel while attending elite college campuses, so we weren’t too surprised to hear that. However, we were surprised to hear about antagonisms that arose within their close friendships with students of the same race but different class.”

The experiences of first-generation, working-class students have long interested Lareau, who previously co-authored a study on adults who are upwardly mobile and has observed many first-generation students struggle on campus for various reasons. “I became interested in understanding more deeply how class and race come together for the lived experiences of first-generation students,” she explains.

After serving as Ferguson’s Ph.D. adviser, Lareau was eager to partner with her on this project. They chose in-depth interviews as a valuable research method for participants to share their experiences and perspectives. “We wanted a deeper dive than a survey. We wanted to hear from the students themselves—to hear their voices—about their experiences in the university setting,” says Lareau.

The 44 interviews demonstrated that Black, white, and Asian American students are experiencing classist interactions with same-race friends characterized by what the authors term as “hostile ignorance." Ferguson defines hostile ignorance as “interactions when more affluent students ask a question or make a comment to working-class students in a critical or hostile manner (rather than a neutral or positive one) on a matter connected to the students’ class position.”

Examples of antagonisms include comments like: You never have money. You’re Asian; why are you struggling academically? You don’t look like you’re poor.

Lareau and Ferguson describe a specific example of a Black student who was shamed by her same-race roommate about her hair. Many of the Black women around her on campus were spending hundreds of dollars on braids, extensions, or twists that they redo or switch up regularly, explains Ferguson. That involves a lot of upkeep and money. “She couldn't afford that, so she was wearing hairstyles past their prime, essentially, and her friend would tell her how unkempt it looked.”

One of the things that is challenging for first-generation students is that the slights and insults can come from not just strangers or acquaintances, but also people in their inner circle.

Lareau puts a fine point on why this is a prime example of hostile ignorance: “Her roommate was from a wealthy family, and she was not sensitive to the student’s economic constraints.”

Ferguson and Lareau’s work spotlights that among the many struggles that first-generation college students might face, hostile ignorance from their wealthier, same-race friends can be a particularly painful one. Lareau says, “One of the things that is challenging for first-generation students is that the slights and insults can come from not just strangers or acquaintances, but also people in their inner circle— roommates and even close friends. This makes the college experience difficult and exhausting. It is hard, at times, for first-generation students to find respite.”

The authors hope their study will broaden the conversation on the experiences of first-generation, working-class students and increase the attention on classism in peer culture, particularly among peers of the same race. Lareau also hopes it will shift the focus from “what first-generations students do or do not do towards the context in which first-generation students attend college and the actions of other students towards them.”