David vs. Goliath

Marci Hamilton, Fels Institute of Government Professor of Practice, has faced down institutional child abuse for decades—and she is just getting started.

Hamilton, Fels Institute of Government Professor of Practice, has waged a career-long effort to protect and find justice for child victims of abuse, whether the crimes are current or decades old. She is the author of Justice Denied: What America Must Do to Protect Its Children, which advocates for the elimination of child sex-abuse statutes of limitations, and God vs. the Gavel: The Perils of Extreme Religious Liberty, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. She has submitted expert testimony, advised legislators in every state where significant reform has occurred, and filed countless pro bono amicus briefs in the U.S. and state supreme courts for the protection of children. Before coming to Penn, Hamilton was a constitutional scholar for 26 years at the Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University, where she held the Paul R. Verkuil Chair in Public Law.

Hamilton was one of the first legal scholars to speak out publicly about the sexual abuse of children by Catholic clergy. As a vocal and influential critic of extreme religious liberty, she has successfully challenged the constitutionality and applicability of laws that provide religious officials a loophole to shield themselves in the legal system. She was the lead constitutional litigator for the victims in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee’s bankruptcy proceedings, during which the Archdiocese argued that religious liberty shielded $50 million from the victims’ claims. Hamilton was victorious, and those funds were made available.

In addition to her legislative and policy work, Hamilton is also a regular in national popular media. She has authored dozens of op-eds in every major newspaper, including a 2018 piece in The New York Times titled, “Let There Be Light, in Church,” which stressed the urgency of abuse reporting by clergy. Television appearances include The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Rachel Maddow Show, where she discussed topics like the crimes of Jeffrey Epstein. She has also participated in numerous documentaries on HBO and other networks, including the recent The Witnesses, about sex abuse in the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and My Truth: The Rape of Two Coreys, which was screened in March at the Directors Guild of America in Los Angeles.

Hamilton is the recipient of numerous honors, including her selection by Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf as a Distinguished Daughter of Pennsylvania in 2019, the 2015 Religious Liberty Award from the American Humanist Association, the 2012 National Crime Victim Bar Association’s Frank Carrington Champion of Civil Justice Award, and the Pennsylvania Woman of the Year Award in 2012—to name just a few.

Hamilton is also the founder and CEO of CHILD USA, a nonprofit dedicated to using interdisciplinary, evidence-based research to prevent abuse, exploitation, and neglect. In addition to its policy work, CHILD USA has numerous initiatives dedicated to fostering public awareness. These include a commission created to investigate the abuse perpetrated by Larry Nasser, former national team doctor for USA Gymnastics and now-convicted serial child molester. The commission has provided victims an opportunity to speak out publicly about the failings of the systems meant to protect them.

So, how did Hamilton, once a budding fiction writer, transition to law and come to take on some of the world’s most powerful institutions? A bit of serendipity, and a lot of refusing to give up—no matter the challenge.

A Pre-Law State of Mind

Upon completing her undergraduate studies at Vanderbilt University, Hamilton decided to pursue a Ph.D. in philosophy at Penn State University. She had always been interested in the crossover between theology and philosophy—a line of thought that informs her work to this day—and existentialism and famed philosophers like Kierkegaard and Nietzsche fascinated her.

But eventually it was writing that became her passion, so after getting a master’s in philosophy, she decided instead to pursue a master’s in creative writing. After graduating from Penn State University in 1984, Hamilton began teaching English at Temple and Drexel Universities in Philadelphia, and writing short fiction, for which she won a national award.

Hamilton had previously considered going to law school. Her grandfather was the District Attorney of Casper, Wyoming, and argued for the state of Wyoming before the Supreme Court. But it was for practical reasons that she eventually rekindled her dreams of law.

“It quickly became clear that there wasn’t any money for me in novels,” laughs Hamilton, who was accepted to Penn Law in 1985. “I went to law school thinking that I would write on the side, but the law swept me up and I was fortunate enough to get wonderful clerkships and start teaching, and instead of fiction, I started writing about legal matters.”

Hamilton hit the ground running, becoming the editor-in-chief of the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, in which she published a note—an article in the world of legal research—on work made for hire copyright laws, which was soon cited by the Supreme Court.

“I thought it was totally unfair that the creative person lost all their rights,” says Hamilton, who became one of the leading experts on the topic in the country. “I testified with musicians Sheryl Crow and Don Henley against a bill that was taking all the rights from the songwriters and giving them to the label,” she says. “We ended up pushing it back.”

Early on, the bishops and the elders would decline to produce evidence, saying that they had a ‘sacred privilege.’ And even when they released lists of known abusers, it was coming from a closed society, where the bishops were the ones vetting these lists and deciding whom to name.

Hamilton’s first clerkship provided her the opportunity to practice law under the guidance of Judge Edward R. Becker in Philadelphia, a graduate of Penn and Yale Law School, known for the humorous and creative wording of his judicial rulings. “He was the mensch of all judges, just a wonderful man. He was fond of telling people, ‘You done good,’” says Hamilton, who is still friends with his family.

Her next clerkship would see her meeting face to face with one of her idols.

On the Shoulders of Giants

On the day of Hamilton’s big interview, nothing was going right. When she exited the train in Washington, D.C., it was pouring buckets. “By the time I got there, the bottom of my gray skirt was black with water,” remembers Hamilton. “My hair was flat against my head, and she just didn’t look like she felt very good. It seemed to me like she was unhappy. After, I went home and I said, ‘That is not happening.’”

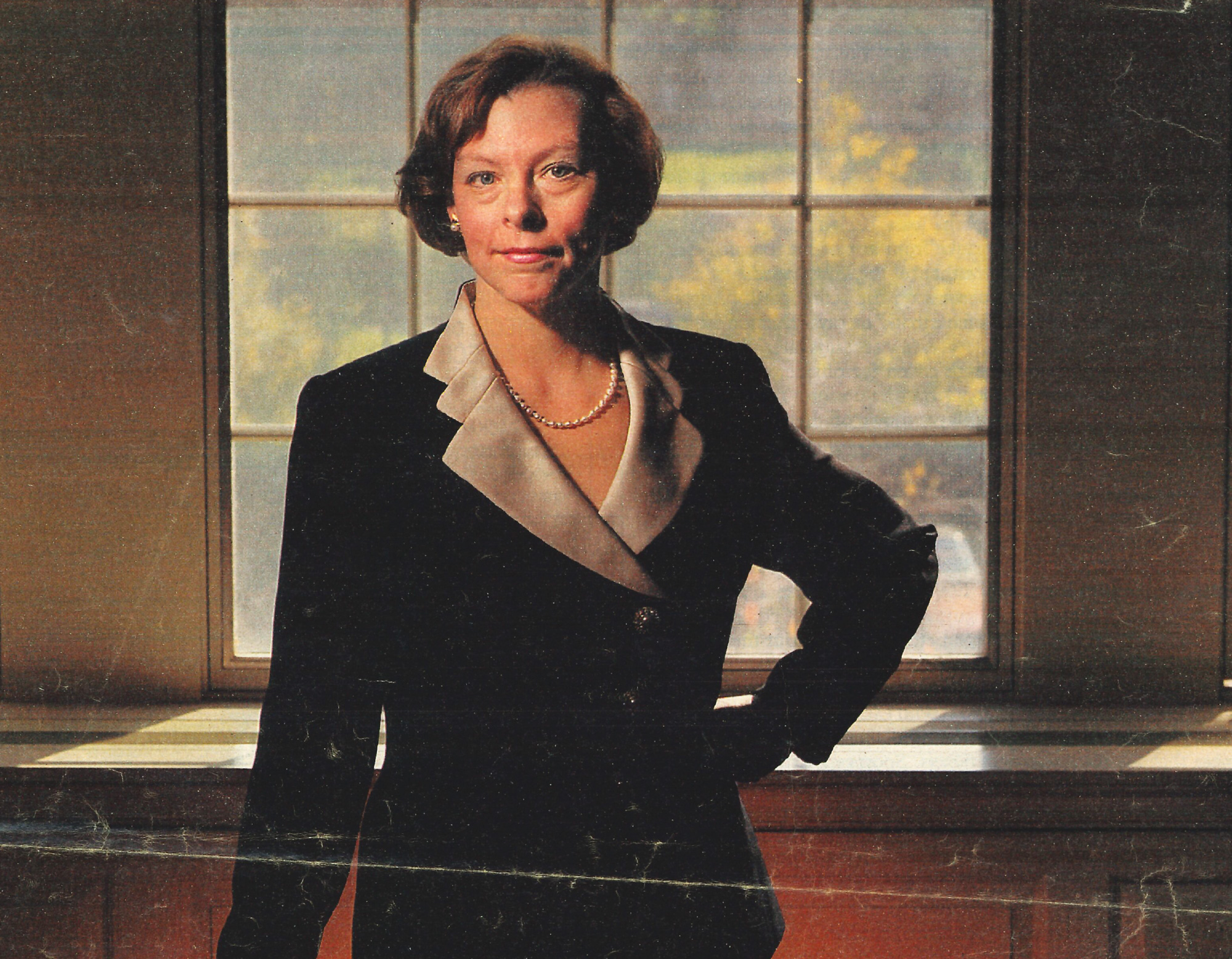

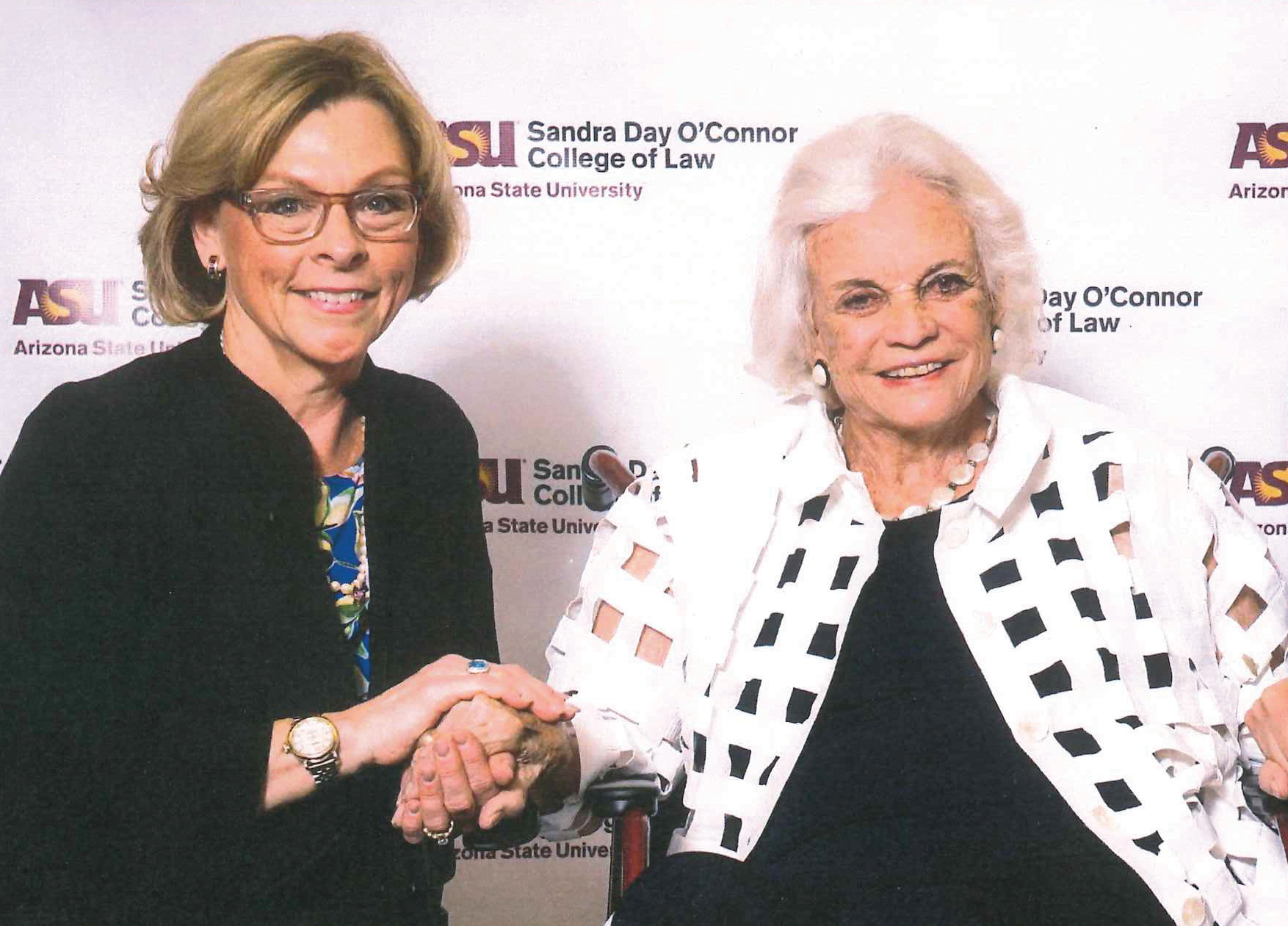

The she in this case was none other than Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Appointed by President Ronald Reagan in 1981, O’Connor is the first woman to have served on the Supreme Court. She presided over numerous landmark cases, including Grutter v. Bollinger, which addressed affirmative action in student admissions, and Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, which dealt with the U.S. government’s power of detainment of enemy combatants, before she retired in 2006.

“It turned out the day after our interview she had her appendix out,” Hamilton says, “which is just so O’Connor. That is just the way she operates. She just powers through. I thought, ‘Well, she’s going to associate me with appendicitis—I’m out.’ So, when she hired me, you could have knocked me over with a feather.”

It was a meeting of kindred spirits, evidenced by the ebullience Hamilton displays at any mention of O’Connor’s name. Hamilton’s tenure under O’Connor, from 1989 to 1990, proved formative, and the justice’s philosophies on religious liberty would impact Hamilton’s very first case—and her policy positions for decades to come.

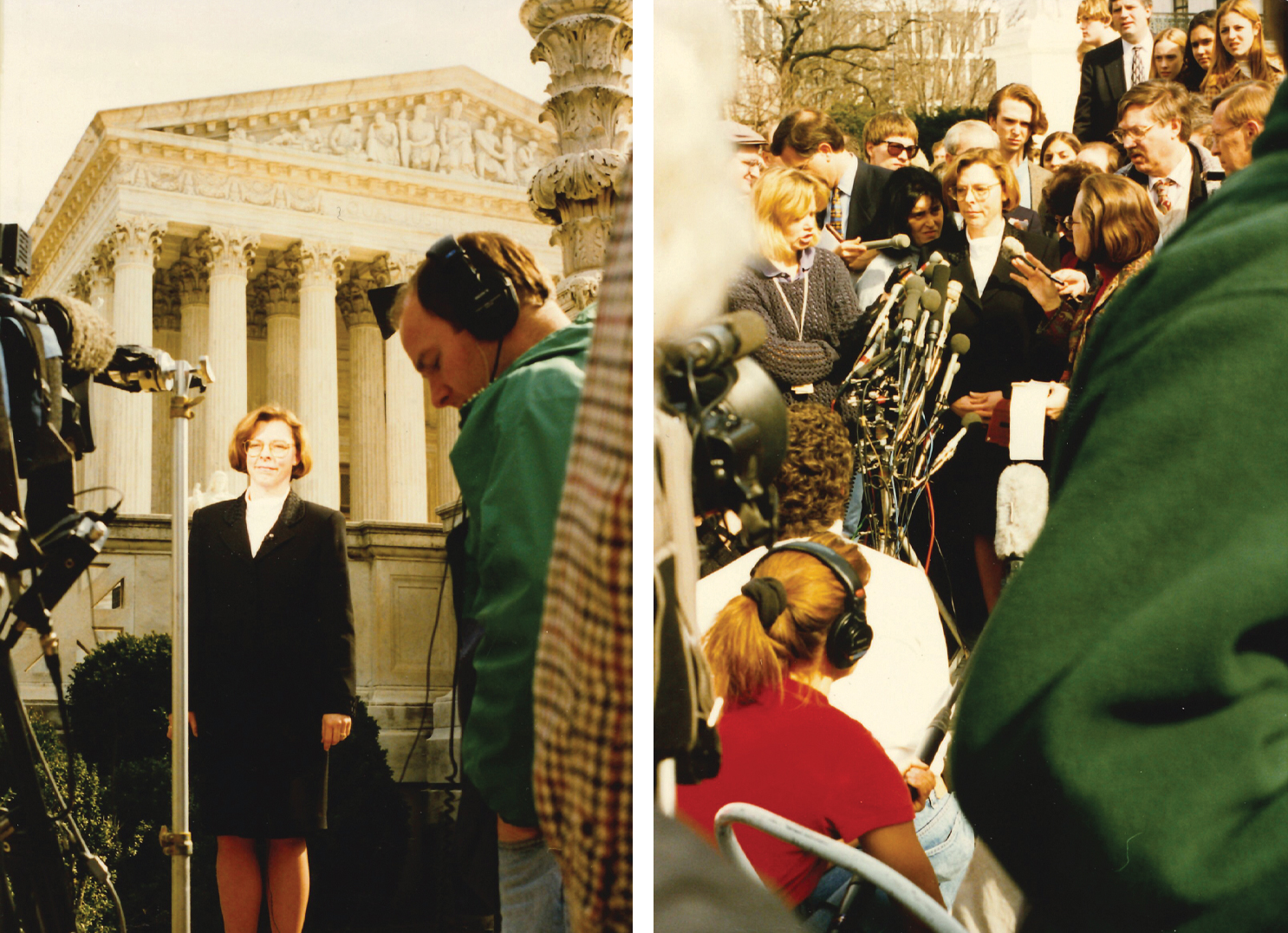

Said case, Boerne v. Flores, came only a few years after Hamilton’s clerkship ended and her career as a law professor began, and just so happened to take place in the Supreme Court—a daunting task for any new lawyer. “With two young children, research and writing, and a full teaching load, it was a busy if not sometimes chaotic time,” says Hamilton. But she had the wind at her back, having already clerked on the big stage.

“I’d never done it before, so I had no idea what I needed to be afraid of,” Hamilton says. “But no one could have done a better job of teaching me about professionalism among disagreeing individuals than O’Connor. She taught me to stand tall for what I believe with dignity and equanimity.”

Into the Fire

Boerne v. Flores, in 1997, saw Hamilton taking on a landmark new law, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), passed in 1993 by the Clinton Administration. RFRA prohibited any agency, department, or official of the federal or state governments from substantially burdening a person’s exercise of religion.

The case stemmed from an incident in which the Catholic Archbishop of San Antonio (Flores) was denied a building permit to expand his church, which was located in a historic district of the city. The Archbishop had challenged the denial under RFRA, arguing that the limited space of the current church created the “burden” so cited in the act.

Hamilton’s team won the case on the ruling that RFRA was unconstitutional because it was beyond the power of Congress. But a very similar bill—which Hamilton repeatedly testified against—was reenacted in 2000, which she says was an early harbinger of the extraordinary influence that evangelical Christianity would have in the White House.

“I was essentially the only law professor in the country who was very publicly saying that extreme religious liberty was wrong. Most of the law professors were on the other side,” says Hamilton.

With the work on her first case, and her scholarly stance on the religion clauses, Hamilton was well positioned to fight the follow-up RFRA bill passed in 2000, as well as emerging state revisions, which she says were empowering individuals to break the law, in ways ranging from the petty—prisoners using religious liberty claims to demand steak and sherry on Fridays—to the dire: priests and bishops covering up sex abuse.

“Early on, the bishops and the elders would decline to produce evidence, saying that they had a ‘sacred privilege,’” says Hamilton. “And even when they released lists of known abusers, it was coming from a closed society, where the bishops were the ones vetting these lists and deciding whom to name.”

Working on all these issues on the opposite side of organized religion had never been part of any plan. My husband’s Catholic and I’m Presbyterian. We’re not atheists by a long shot. But when all the clergy sex abuse reporting started happening, I began getting calls from all over the country.

An interesting trend occurred following the Supreme Court victory. Hamilton began to hear from child protection advocates, mayors, state attorneys general, and organizations like the National Association of Regulatory Agencies—parties that were all fighting against institutional child abuse.

“Working on all these issues on the opposite side of organized religion had never been part of any plan,” says Hamilton. “My husband’s Catholic and I’m Presbyterian. We’re not atheists by a long shot. But when all the clergy sex abuse reporting started happening, I began getting calls from all over the country.”

But many victims, after making the difficult decision to come forward, were met with closed courthouse doors due to statutes of limitations—laws that set the maximum time after an event within which legal proceedings may be initiated. “It was outrageous that this artificial deadline could have such unjust consequences,” Hamilton says. “I knew immediately I had to do something to stop it.”

The Dam Breaks

Hamilton marks the 2002 Boston Globe “Spotlight Investigation: Abuse in the Catholic Church” report—an in-depth investigation into systemic child sex abuse in the Boston area by Catholic clergy, which spawned the 2015 award-winning film, Spotlight—as the beginning of a focused push for statutes of limitations reform.

Battling for justice on this front became Hamilton’s prime directive. In most states, before any reform, victims had only two years from the date of the sex abuse to go to court. Therefore, a five-year-old only had until age seven. Yet, as the floodgates opened and more and more incriminating evidence became public, the discussion surrounding the rights of victims became more intense.

“Before the investigation, we knew about some individual abusers, but we didn’t know the extent of the cover-up by trusted institutions,” says Hamilton.

After the Spotlight report was released, California implemented the first “open window,” which granted one year in which there was no statute of limitations for child sex abuse. There were about 1,150 claims, Hamilton says—and about 850 of them were directly linked to the Catholic Church.

“All of a sudden, the public started learning that Boston was just the beginning,” Hamilton says.

In 2005, Lynne Abraham, then District Attorney of the City of Philadelphia, published a report on sex abuse in the Philadelphia Archdiocese. Hamilton joined the team as the only non-staff person to work on the legal recommendations. The collective’s arguments for opening the doors to justice continued to shed light on the issues surrounding statutes of limitations reform. In 2007, Delaware implemented a two-year open window. It revealed sex abuse in many different institutions and uncovered abuse by perpetrators such as former pediatrician and now-convicted serial child molester Earl Bradley, who victimized hundreds of children and infants. Other states began to follow suit, but reform was still a heated battle in many states.

“Currently, we have 46 states that have eliminated the criminal statute of limitations, and 2019 was a banner year. So, the progress has been extraordinary,” says Hamilton.

“I started hiring more and more research assistants to document and promote access to justice for child sex abuse victims,” she says. “After a number of years, I finally realized that if I didn’t start a nonprofit, I couldn’t do anything more than I was doing.”

Fighting Abuse With Data

In 2016, Hamilton returned to Penn in the role of Professor of Practice, a position designed to bring faculty expertise into the classroom, a valuable asset for students interested in advocacy. That same year, she launched CHILD USA, a nonprofit think tank dedicated to ending child abuse and neglect using comprehensive legal and social science research. The organization pursues a wide swath of initiatives. This includes the familiar-to-Hamilton statutes of limitations reform, but also the abuse and neglect of athletes, medical neglect, conversion therapy, family court reform, the handling of children’s rape kits, child marriage, and more.

CHILD USA houses the Sean P. McIlmail Statute of Limitations Research Institute, which Hamilton says is funded by, “a remarkable family whose son died of a drug overdose while coping with the stress of prosecuting his perpetrator, a priest.” Institute legal staff track data on a weekly basis, a necessary process as these policies are on a rapid trajectory of improvement, in no small part due to Hamilton’s work in the field.

Even today, people view sex abuse as an injury that can be treated and healed. But we need to keep in mind that it’s much more complex than that.

“We live in this era of exploding data—on children, child development, trauma, and incidents of abuse and neglect,” says Hamilton, who also advises foreign governments on child abuse prevention policy. “We need all these organizations that are doing direct service, but we also need an organization like ours that is thinking big picture. And that means strategizing about how we change the system as a whole.”

One of Hamilton’s biggest challenges on the policy reform front is educating uninformed officials. “A decade ago I had lawmakers that refused to meet with me under the misperception that somehow I was in there to argue against the Catholic Church,” she says. “That’s changed dramatically, but what people need to remember is that policymakers require data to be able to make a difference. Unfortunately, you can’t just line up victims and say, ‘These are horrific stories. Let’s do something just for them.’ I wish it were that simple, but it isn’t.”

The single most important statistic when it comes to statutes of limitations reform, Hamilton says, is the age at which the average child abuse victim first comes forward: 52. The complex psychological dynamic of trauma and reporting plays directly against the victim, she says, a web that often leaves them without justice.

“Even today, people view sex abuse as an injury that can be treated and healed,” Hamilton says. “But we need to keep in mind that it’s much more complex than that. Victims usually feel immensely threatened, and the humiliation and shame and trauma keep them quiet. They have to get around things like depression and PTSD and substance abuse. It’s asking a lot of any victim.”

And the barriers to justice for victims go beyond the legal lobby. One of the main fronts in the fight for justice for victims is the insurance lobby.

“The insurance industry covers these organizations for negligence, and they don’t want to pay out claims, so their lobby is aligned against the victims,” says Hamilton. “But the insurance industry needs to get on the side of the children and become part of the prevention. Instead of fighting the truth from coming out, they should start doing an annual child protection audit. If an organization does not pass the child protection audit, it doesn’t get insurance. And in this culture, if you don’t get insurance, you don’t exist.”

Out of the Shadows

One of the initiatives gaining the most steam at CHILD USA is the fight against the abuse and neglect of young athletes. The nonprofit recently created the initiative Game Over: Commission to Protect Youth Athletes. Composed of 16 experts in the field, the commission is engaging in fact finding and the investigation of all responsible institutions and individuals that made it possible for Larry Nasser, former national team doctor for USA Gymnastics and osteopathic physician at Michigan State University, and now-convicted serial child molester, to abuse hundreds of young athletes. The commission has held public hearings, giving victims a voice, and will issue a report on its findings. It is also building a database that will eventually be made available to the public.

Many times, telling your story is not enough. There has to be meaningful pressure. Whether it’s Catholics, ultra-Orthodox Jews, people in the Boy Scout culture, or Penn State, people have to be able to say, ‘I love that institution, but I can’t agree with what they’ve done with respect to children.’

“Sometimes it may look like the system is being survivor-friendly, but what these victims are testifying to is that everyone from sports watchdog agencies to the FBI to local law enforcement let them down,” says Hamilton, who frequently authors op-eds on breaking news stories related to child abuse in order to bring scandals into public view.

The stories coming out of the trials are revealing.

“Volleyball player Sarah Powers Barnhard, who had outed her abuser decades ago, was on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1996 for her bravery, but she didn’t get him fully expelled from the sport until 2018,” Hamilton says. “So, many times, telling your story is not enough. There has to be meaningful pressure. Whether it’s Catholics, ultra-Orthodox Jews, people in the Boy Scout culture, or Penn State, people have to be able to say, ‘I love that institution, but I can’t agree with what they’ve done with respect to children.’”

The fight for justice extends to any and all organizations that harbor abusers, Hamilton says.

CHILD USA has now been asked to analyze data on approximately 1,500 child sex abuse victims of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), which has filed for national bankruptcy. “These facts are critically important to understand how the BSA has endangered boys and what must change in the future,” Hamilton says.

Multiple Fronts

This past March, along with her co-counsel attorneys Brian Kent and Jeffrey Fritz, Hamilton made history when she filed the first two lawsuits against the Church of Scientology for child sex abuse, brought “by two extraordinarily brave survivors,” Hamilton says.

“These lawsuits are historic because this organization has been very effective at silencing its victims even in the Me Too era,” she continues. “The statute of limitations window legislation that CHILD USA fights for is one reason that these victims have a chance at justice.”

Hamilton also filed legal arguments against mandatory religious arbitration for the alleged rape victims of actor and scientologist Danny Masterson. “It is unconstitutional and cruel to force a rape victim who has left the faith to be forced into religious arbitration regarding the rape, and the harassment from the religious organization that followed.”

CHILD USA is also taking on programming that Hamilton says is fraught with potential for abuse, like conversion therapy, a practice employed to “convert” homosexual youths to heterosexuality, which is widely considered abusive.

“I was already interested in religious camps for children that were engaging in abusive practices, and some conversion camps, which have been known to use methods like creating aversion through electric shock, fit that same mold,” says Hamilton. “To this end, we are seeking out past participants of this practice—whether in a camp or through private counseling—so we can gather experiential data, because there really have not been strong social science studies on harmful practices like these.”

These social concerns extend to medical neglect and family court. Because Hamilton’s wheelhouse is the intersection of religion and law, she is well-positioned to advocate for children whose parents refuse essential medical care for religious or philosophical reasons.

When it comes to family court, Hamilton says there is a whirlwind dynamic that often works against the mothers of abused children. She describes a scenario she has witnessed: “A mother discovers her child’s father is being sexually abusive and rushes to authorities to institute divorce proceedings. In family court, the man, who is the breadwinner, shows up cool and calm and claims that the mother is trying to alienate him by making up stories. The judge gives the father dual or sole custody, placing the child back in the presence of the abuser.”

Hamilton says in these scenarios, it’s the child who becomes trapped. “The sad truth that people need to understand is the child probably loves the father who is sexually abusing them. A child just doesn’t understand,” continues Hamilton, who cites CHILD USA staff member Danielle Pollack, one of these same protective mothers who was ignored by the court, as a wonderful resource and ambassador for those the nonprofit is trying to help. “Family court judges are simply not adequately trained to handle the nuances of the cases.”

An Unrelenting Fight

Hamilton hasn’t given up on the idea of cozying up on the shore to write a fiction novel. She is currently at work on a historical project of a different sort, which explores the framers of the Constitutions’ interaction with Calvinism and how that laid the groundwork for the baseline of the Constitution: expect those with power to abuse it.

In addition to her advocacy and research, Hamilton is still passionate about teaching. “In my Children and the Law class, I had a wonderful group of students, including a public school principal, an Army major, an education graduate student, and even a former worker in the foster care system,” she says. “There are such incredible insights to be had, and those insights inform my policy work. I just want to sit and speak with them all day.”

CHILD USA is making headway on its initiatives each and every day. Reflecting on her decades of pioneering work, Hamilton considers herself the luckiest woman in the world.

“I’ve been given a calling that just happens to be at the right time and in the right place. It’s what children need, and what the country needs,” says Hamilton. “It’s getting better incrementally, but every day I wake up and there’s another frontier that we need to civilize. As soon as my team and I solve one challenge, we just take that pin off the board and tack another one on.”