The Clues in the Chemistry

Childhood curiosity led Joseph S. Francisco, President’s Distinguished Professor of Earth and Environmental Science, to a career as one of the country’s most prominent atmospheric chemists.

The foggy days stayed with him. It was on foggy days, the kind where a fine mist held in the air, that Joe Francisco noticed that the young women at Lamar University were reluctant to leave the student union and head to class. On foggy days, their stockings melted on their skin and silk scarves became dotted with holes.

Francisco was a high school student hanging out at Lamar, in Beaumont, Texas, for a couple of reasons. For one, it was pretty cool to tell his friends that he’d spent the weekend mingling with college students. And Lamar had a whole building dedicated to chemistry—also pretty cool to a budding scientist. Back then, in the early 1970s, Francisco had no way of knowing that the strange fog had anything to do with the nearby oil refinery. No one did.

“At that time, we did not know anything about acid rain,” Francisco, President’s Distinguished Professor of Earth and Environmental Science, recalls.

In the mid-to-late 1970s, scientists began publishing about acid rain and the underlying chemistry behind it. Research revealed that crude oil when processed, like from the refinery in Beaumont, emits sulfur dioxide, which then oxidizes. The result can lead to an acid rain event, which can have widespread ecological effects. And, as it turns out, melt nylon stockings. Modeling showed that the oxidation process took about 13 days. But fog didn’t hang over Beaumont for that long.

“The research out of the ’70s and ’80s was correct. No qualms about it,” says Francisco. “But it couldn’t explain what I saw and what others experienced. There had to be something else.”

When he came to Penn in 2018, Francisco, who is also a professor of chemistry and the former president of the American Chemical Society (ACS), set out to find what was missing. With his research group, he discovered a new mechanism for acid rain generation. The results were published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society in 2019 and more recent experimental validation came in that same journal in 2022. Decades later, the high school kid hanging out at the student union had found an explanation behind the foggy-day phenomenon.

Francisco’s career has taken him from his student days at the University of Texas at Austin and Massachusetts Institute of Technology to professorships at Purdue University, the University of Nebraska, and Penn. He now lives in Philadelphia with his wife, Priya, an economist, and their three daughters. He’s held research positions at the University of Sydney, the University of Cambridge, and the Jet Propulsion Lab at the California Institute of Technology. He has published more than 700 journal articles, written 10 book chapters, and co-authored the textbook Chemical Kinetics and Dynamics. His accolades and recognition include memberships in the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society, as well as election to the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina and awards from the National Science Foundation and American Chemical Society.

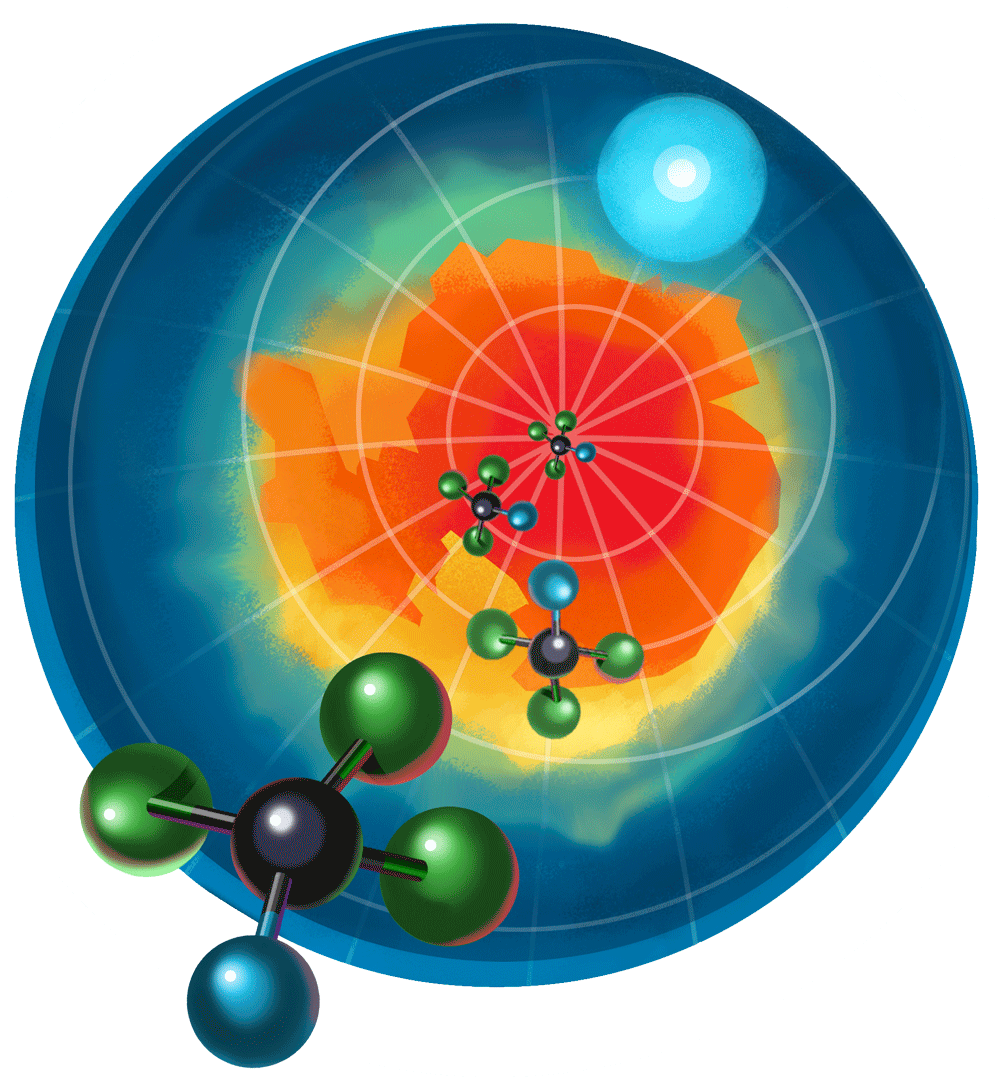

Chief among his scientific achievements is the application of new computational tools of physical chemistry to bring deep insight into the underlying chemistry of the atmosphere. “The problem with the existing experimental techniques is that they destroyed some of the critical chemistry in their processes,” Francisco says. “So, what we did was use computational chemistry.”

He describes how he and his research team used computer modeling to determine all possible reactions that might occur if certain chemicals were released into the atmosphere. At the time, fellow scientists were suspicious of computational chemistry results. But Francisco persisted, certain that the findings could provide a roadmap for new discoveries by suggesting where in the atmosphere to look and what type of chemistry to look for. “What started happening,” he says, “is that we began to discover things that people had missed for 50 years, simply because they didn’t know where to look.”

Looking at chemistry on other planets has always given us inspiration. What we’ve learned from those planets and the atmospheric conditions on those planets can guide us in terms of how to make life better on our own planet.

Francisco’s methods and curiosity have taken him to the atmosphere, the stratosphere, and different planets, but he always has Earth in mind. Take Venus, for example. The second planet from the sun has a significant amount of chlorine in its atmosphere, and the element exhibits similar chemical behaviors on Venus and Earth. So, when investigating how chlorine levels affect our planet’s ozone layer, Venus provides a good model and reference. Its gas makeup also means that Venus experiences what Francisco calls “runaway global warming.” Studying the gases in Venus’s atmosphere gives scientists insight into the effect our own changing atmosphere may have on global temperatures.

“Looking at chemistry on other planets has always given us inspiration,” Francisco says. “What we’ve learned from those planets and the atmospheric conditions on those planets can guide us in terms of how to make life better on our own planet.”

Lifelong Learner

Analyzing the chlorine- and sulfur-rich chemistry of Venus is pretty advanced stuff, but everybody has to start somewhere. Francisco started on the railroad tracks in Beaumont, tracks that carried chemicals from cargo ships in the Gulf of Mexico to local oil refineries. Inevitably, there were spills. “As a kid, I was curious about it: What were those things on the railroad track?” he remembers. “I would kind of do the smell test and do the touch test. Thank God I didn’t do the taste test!” Not content with what his senses could tell him, Francisco headed to the library to learn more. A high school job at a pharmacy only increased his interest in chemistry.

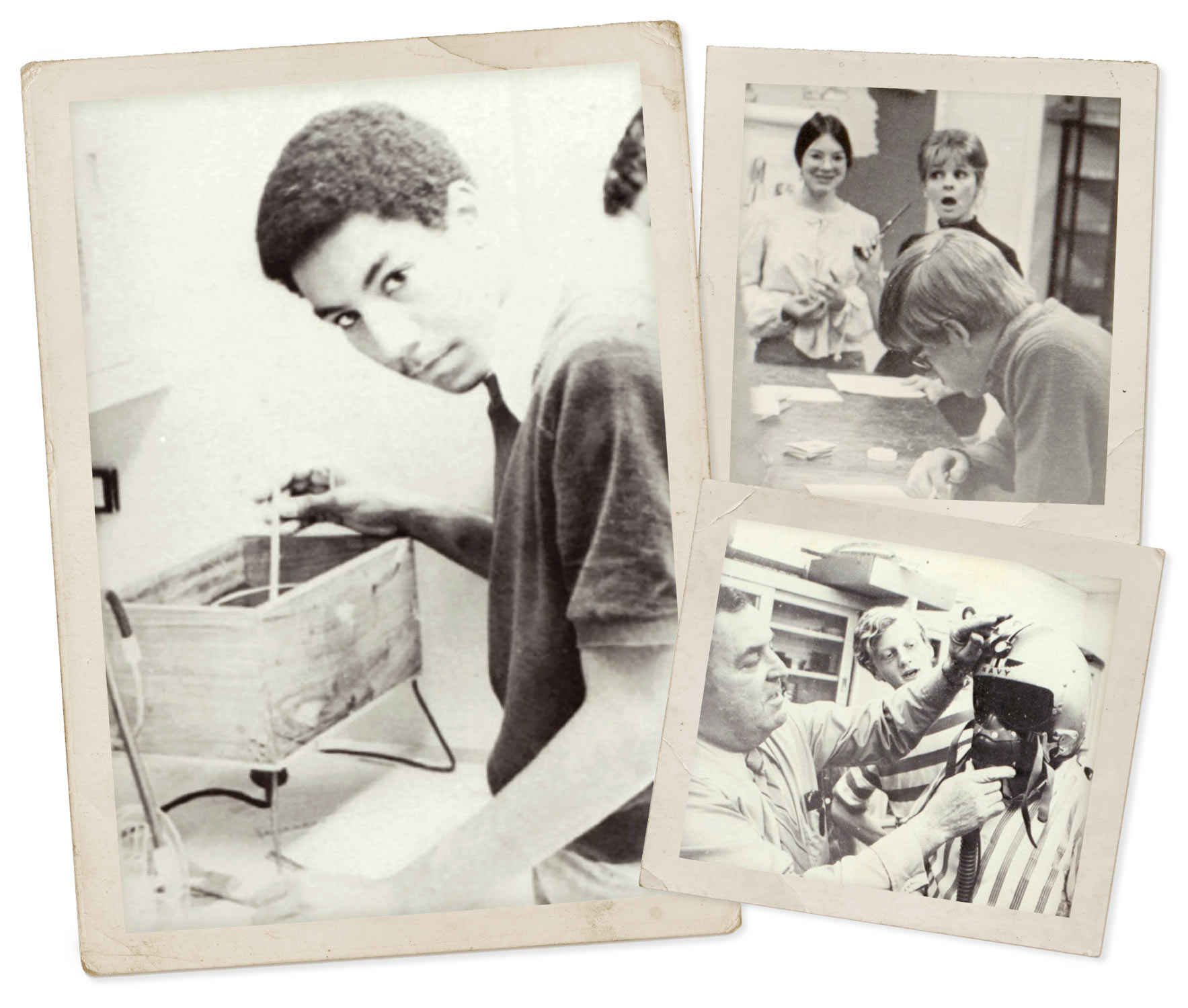

That led him to the campus of Lamar, where he made the foggy- day observation that stayed with him for decades. At first, Francisco hung around the student union and kept his eye on the chemistry building, wondering what it would be like to be a college student. A faculty member took notice and gave him a tour, showing him a gas chromatography instrument, a tool that can separate a mixture into its chemical components. Francisco’s reaction? “Wow, I think I can build one of those.”

He got to work gathering materials at the city dump. He’d then bike the parts over to his high school physics teacher’s house, where the young Francisco had permission to use the teacher’s machine shop. A chemistry teacher got in on the act and enrolled the homemade chromatography apparatus in a state-wide science competition, which Francisco won. “It actually worked,” he says. “And you didn’t have to spend $50,000. You could just build one out of junk.”

I’m just very, very grateful to some good high school teachers who had a real belief in me. They saw something in me and wanted to make sure that I had an opportunity to grow my interest and my curiosity.

Despite Francisco’s talent for chemistry, college wasn’t a given for him. In fact, he didn’t even apply. No one had ever talked to him about college or what the application process entailed. So, he was surprised when he got a call from a professor in chemical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin saying that he’d been admitted. Turns out, his chemistry and physics teachers had submitted an application on his behalf.

“I’m just very, very grateful to some good high school teachers who had a real belief in me,” Francisco says. “They saw something in me and wanted to make sure that I had an opportunity to grow my interest and my curiosity.”

The number of teachers who saw Francisco’s talent and skill only grew as his education continued. Recalling his first college chemistry course, Francisco says, “I was one of two African American students in a class of 350. Toward the end of the semester, the professor called me into his office and I thought, ‘Uh oh, I’m in trouble.’” As it turned out, the professor, Raymond E. Davis, wanted to gauge Francisco’s interest in research. Francisco jumped at the opportunity and became the lone freshman in a lab of graduate students and postdoctoral fellows researching X-ray crystallography, a topic he continues to study today.

By his sophomore year, Francisco knew he wanted to make a career in research, and by junior year, he was taking graduate courses. He considered a variety of graduate schools but ended up choosing the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where his research took a new direction thanks to a surprising source.

“Back in 1977, there was a cool movie that came out called Star Wars, and in that cool movie there was the lightsaber,” he says. “I just found that so interesting. At MIT, they had a number of people doing research with lasers, in particular, how does laser light interact with chemical entities? What does that do to the properties of molecules? The coupling of physics and chemistry, for me, was fascinating.”

As a graduate student, Francisco began publishing papers. One day, a man with a “funny accent” showed up at the lab and invited him out to lunch. “And what graduate student would turn down a free lunch?” Francisco asks. That man was Robert Gilbert from the University of Sydney, and Francisco ended up getting more than just a meal. Their meeting concluded with an invitation to research alongside Gilbert, and before long, Francisco was on his way to Australia for a six-month stay.

When he was back stateside finishing his doctorate at MIT, another man with another accent showed up at the lab. This time, it was a researcher from the University of Oxford who had heard about Francisco from Australian colleagues. Francisco was, as he jokes, “geographically challenged,” and he wondered if the visit presented him an opportunity to return to Texas. Oxford, Texas, that is, some 300 miles west of Beaumont. Alas, the visiting scientist was from Oxford, England, but he did get Francisco to consider another international research experience. After graduating from MIT, he headed to the University of Cambridge for a postdoctoral fellowship.

When his postdoc finished, Francisco was at a crossroads. Head back to the United States, or stay in England? He considered a job opportunity that would have allowed him the best of both: A British manufacturing company with a U.S. branch needed a scientist well-versed in American and British systems. In the end, Francisco knew that research was too important to him and his path was in academia. “Research has always been fun for me,” he explains. “It allows me to explore my curiosity and keep learning.”

Taking the Lead

Francisco’s education was marked by teachers and mentors who believed in him, inspired him, and challenged him. Once established in his career, student became master. Or, to harken back to the “cool movie” that shaped his doctoral research, Luke became Obi-Wan. Through his teaching and leadership roles with the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers (NOBCChE) and the ACS, Francisco has sought to introduce the next generation of scientists to new and ever-expanding opportunities.

NOBCChE, an organization founded in the early 1970s to promote the professional advancement and development of Black chemists and chemical engineers, is now largely focused on education starting at the K-12 level. From 2005 to 2007 Francisco was the NOBCChE president, a role he remains proud of. After his tenure as president ended, he thought his days of national leadership were done. But the American Chemical Society had noticed his work with NOBCChE and asked him to consider running for the ACS presidency.

“When I got that call, I thought one of my students was pranking me,” Francisco remembers.

Once he was sure the invitation wasn’t a prank, he had some thinking to do. The ACS presidency would be a demanding job, on top of his responsibilities as a professor and researcher. What could he accomplish in that role?

Ultimately, Francisco ran and was elected on a platform of preparing students for a world of global chemistry and entrepreneurship. Making it happen involved changes to undergraduate and graduate curricula and creating international exchange programs with businesses and educational institutions. Today, ACS offers resources to guide undergraduates in selecting a study-abroad program and career planning workshops for graduate students interested in pursuing positions in academia, government, industry, and nonprofit work.

More recently, Francisco took the helm as co-lead of the Penn Environmental Innovations Initiative. Along with Kathleen Morrison, Sally and Alvin V. Shoemaker Professor of Anthropology, Francisco directs the initiative in its mission to meaningfully impact environmental challenges. Founded in 2020, the group works to facilitate innovative research, helps to recruit and retain outstanding faculty members, and develops educational programs.

Working across the University is key to the initiative’s mission. And it’s part of what drew Francisco to Penn in the first place.

Many places use buzzwords like “interdisciplinary” and “transdisciplinary,” but Penn actually made it happen, he says. “The structure was there to make it easier for students and researchers to work across boundaries.”

He adds, “The opportunity to lead the Environmental Innovations Initiative was a chance to build upon Penn’s rich history of multidisciplinarity, but within the modern context, make it very impactful.”

Since the initiative launched, Francisco, Morrison, and a team of faculty advisors and staff have created connections across Penn and around the world. They started a faculty fellowship program that includes representatives from each of Penn’s 12 schools and worked with each school to establish a set of tailored Academic Climate Commitments. The initiative builds local and global partnerships with community collaborations at events from Penn Climate Week to the U.N. climate change conference (COP 27) held in Egypt in November 2022.

Catalyst for Change

The accolades and leadership roles are nice—they allow Francisco to advocate for the type of large-scale change that can affect the state of education for generations of students—but it is important to Francisco that he connects with students individually, too. He remembers the teachers who motivated him and how thrilling he found research, even as a young man.

“In my experience,” he says, “getting a student involved in research can be transformative. If a student tells me they find research exciting, I want to create as many opportunities as possible for them to explore their curiosity and make what is in the textbook come alive. The whole process is fun, and I want them to see that.”

Throughout his career, Francisco has retained the curiosity that motivated his first experiments on the railroad tracks in Beaumont. Back then, he had no idea what those spills meant for him and his community.

In my experience, getting a student involved in research can be transformative. If a student tells me they find research exciting, I want to create as many opportunities as possible for them to explore their curiosity and make what is in the textbook come alive.

“This was before there was any talk of environmental justice. We had chemical explosions practically every year. Refineries were right smack in minority communities,” he says. “We had no idea what was being released into the atmosphere and we had no understanding of how people’s health was being compromised. And surely, health was being compromised. I know mine was.”

He remembers frequent childhood asthma attacks that ceased when he left his hometown and had distance from the refineries and the chemicals they released into the atmosphere. He explains, “At the time, I didn’t know why I had asthma attacks in Beaumont but not in Austin. We didn’t make the kinds of connections we’re able to make today.”

Now, Francisco says that education is the most important tool in combating climate change and working for environmental justice. Atmospheric chemistry has a role to play, from investigating how the release of chemicals affects the ozone layer and our warming planet to the chemistry of our own bodies. Sometimes this research causes pushback, like early in Francisco’s career, when he began researching chlorofluorocarbons, manmade compounds of carbon, chlorine, and fluorine that function as coolants in refrigeration systems, among other uses.

The use of chlorofluorocarbons in consumer products such as vehicles and refrigerators required that they be extremely stable in the face of extreme heat or fire. The prevailing wisdom went, due to their stability in harsh environments, the compounds could not pose a safety risk when released into the atmosphere. But Francisco wasn’t so sure. “Their stability turns against them,” he explains. His computational research showed that when the compound was unreactive in the atmosphere, it could be transported to the stratosphere, where it would break down and damage the ozone shield.

“The chemical companies weren’t too happy” when he presented and published that research, Francisco recalls. Despite some external pressure to halt this work, university leadership was supportive, and Francisco believed in the validity of the research. He kept at it and other scientists began to validate his findings.

Years later, at an international conference where he was presenting on his ongoing chlorine chemistry research, he got a vote of confidence from a surprising source. A group of scientists from a company that produced chlorofluorocarbons approached him. “Joe, we knew you were right,” they said. “We were rooting for you 100 percent.” Though it took years, Francisco was glad to hear it. And, he says, the experience showed him how important it is to believe in yourself in the face of doubt.

His persistence in chlorofluorocarbon research opened new doors for his field. “It was an exciting time,” he says. “I’ve been credited with showing the value of atmospheric computational chemistry as a new field, but I didn’t realize that’s what I was doing at the time. It was fun!”

Now, Francisco is decades into his career. But he’s still having fun, still making discoveries, and still championing education.

“Since I’ve been at Penn, I’ve been exploring new areas, like aerosol surfaces and cloud droplets,” he says. “How do those environments alter chemistry we previously thought was well-known? And we’ve been discovering stuff that is just incredible—a whole new set of chemical processes.”

These new discoveries relate to our health. “If you consider the air that we breathe, how do chemicals and pollutants interact with the surface of lung tissue?” he asks. “Right now, we’re trying to understand the chemistry, and once we do, we can consider the broader implications for public health.”

Making these types of discoveries is thrilling for Francisco, who has dedicated his career to his curiosity. But they are also exciting for students who realize just how much more there is to learn. For Francisco, it is imperative that students have the tools to keep asking questions, questioning accepted wisdom, and pushing the boundaries of the discipline. It’s key for the future of chemistry and the future of our planet.

“We need to educate our students so they can be informed citizens,” he says. “That’s the power of educational institutions. I’m not saying we should tell students what to do, but we need to really help them to figure out how to make important decisions on their own with the information that’s available. For me, it is what our mission calls for.”