Bringing History to the Surface

Mantha Zarmakoupi, Morris Russell and Josephine Chidsey Williams Assistant Professor in Roman Architecture, conducts underwater surveys to map ancient travel and political intrigue.

For Mantha Zarmakoupi, an archaeological survey isn’t just about the artifacts—it’s about reliving the human experience.

“We were cleaning debris from a building that had fallen off a cliff on the island of Kythnos, and I saw this piece of clay with the imprint of a finger,” says Zarmakoupi, Morris Russell and Josephine Chidsey Williams Assistant Professor in Roman Architecture in the Department of History of Art. “I remember the human touch of this object, the memory of the person who probably put the clay in that mold, rather than what we value in archeology—the seal.”

Mantha Zarmakoupi, Morris Russell and Josephine Chidsey Williams Assistant Professor in Roman Architecture

Zarmakoupi’s research focuses on the broader social, economic, and cultural conditions underpinning the creation of ancient art, architecture, and urbanism, and the ways in which the cultural interaction between Greeks and Romans informed their artistic production and built environment. Her publications include Designing for Luxury on the Bay of Naples (c. 100 B.C.E. – 79 C.E.): Villas and Landscapes, and “Balancing Acts Between Ancient and Modern Cities.”

Zarmakoupi’s investigative work isn’t limited to land. In 2014, she initiated an underwater survey around Delos, the home of the sanctuary of Apollo since the archaic period and an important trading point in the late Hellenistic period. An accomplished diver, she ventures into the depths off the shores of largely uninhabited Greek islands whose mysterious histories could reveal the intricacies of ancient Greek maritime networks and political intrigue. In 2019, working alongside her co-director George Koutsouflakis, Head of the Department of Underwater Archaeological Sites, Monuments, and Research in the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities in the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports in Greece, Zarmakoupi started surveying Mediterranean shipwrecks around the islands of Levitha, Kinaros, and Maura.

Levitha, located in the east of the Aegean Sea, isn’t completely uninhabited. For over 150 years, the Kamposos family has farmed and tended goats, and run a small taverna restaurant, which, for the surveyors, became a place for respite and discussion of findings among the researchers and with the family. Developing this relationship was crucial to both their research—the family was the team’s first stop for anecdotal evidence of shipwrecks—and to build trust.

“The people that live on the islands are afraid that if the archeologists come they will take this land away from them,” Zarmakoupi says. “They want the history to have some attention, but they are a bit suspicious of any authority coming on the island.”

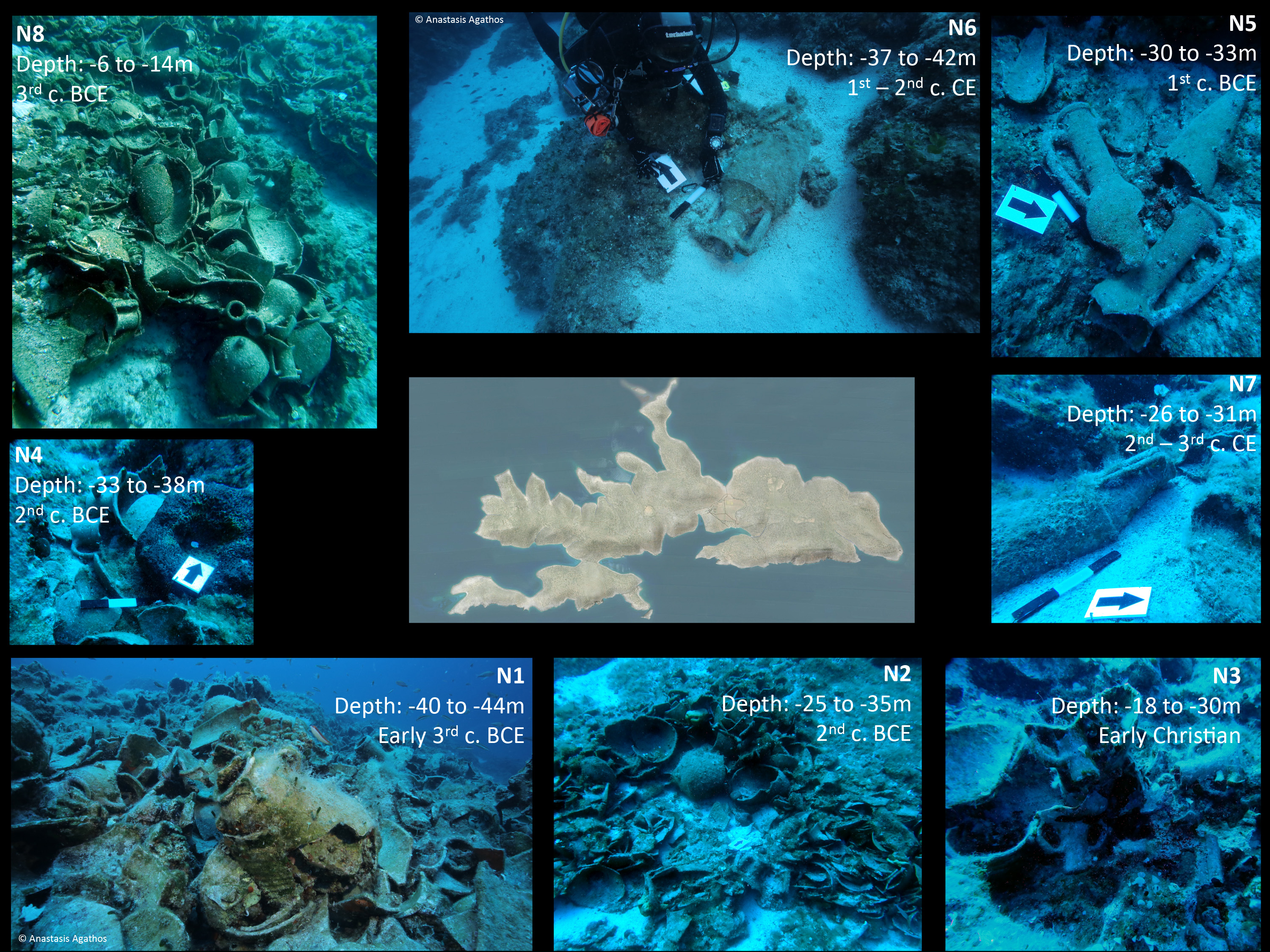

The Levitha survey team was comprised of people from the Ephoria, the institution that supervises underwater archeological work in Greece; students from the University of Athens; and William Pedrick, GR’19. The team depends on local knowledge—the Kamposos family helped to map out each of the harbors around Levitha. The team then began navigating the coastline at a depth of 10 to 40 meters, charting a series of shipwrecks that date from the Hellenistic to the Byzantine periods. Zarmakoupi says the shipwrecks, coupled with acropolis and watchtower ruins found on the island, suggest competing powers in the Aegean in the Hellenistic periods. This fits with historical sources that cite similar narratives regarding other nearby islands, like Delos.

The team brought up a number of amphorae—a type of container—from each site, to clean and draw and then date. To the family that had fed them each day and lent them local lore, the survey team temporarily left a larger-than-life relic: an ancient anchor stock. The family will safeguard it before transporting it to Athens.

“I believe this is a part of our mission in archeology,” Zarmakoupi says. “The more you speak about the finds and communicate why they’re important to the community, the more they are informed. This creates less tension and avoids opportunistic excavations.”