It’s not every day that scientists get to say they have discovered a new planet in our solar system, but that day arrived this past July for Masao Sako, an associate professor of physics and astronomy, and Gary Bernstein, the Reese W. Flower Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics.

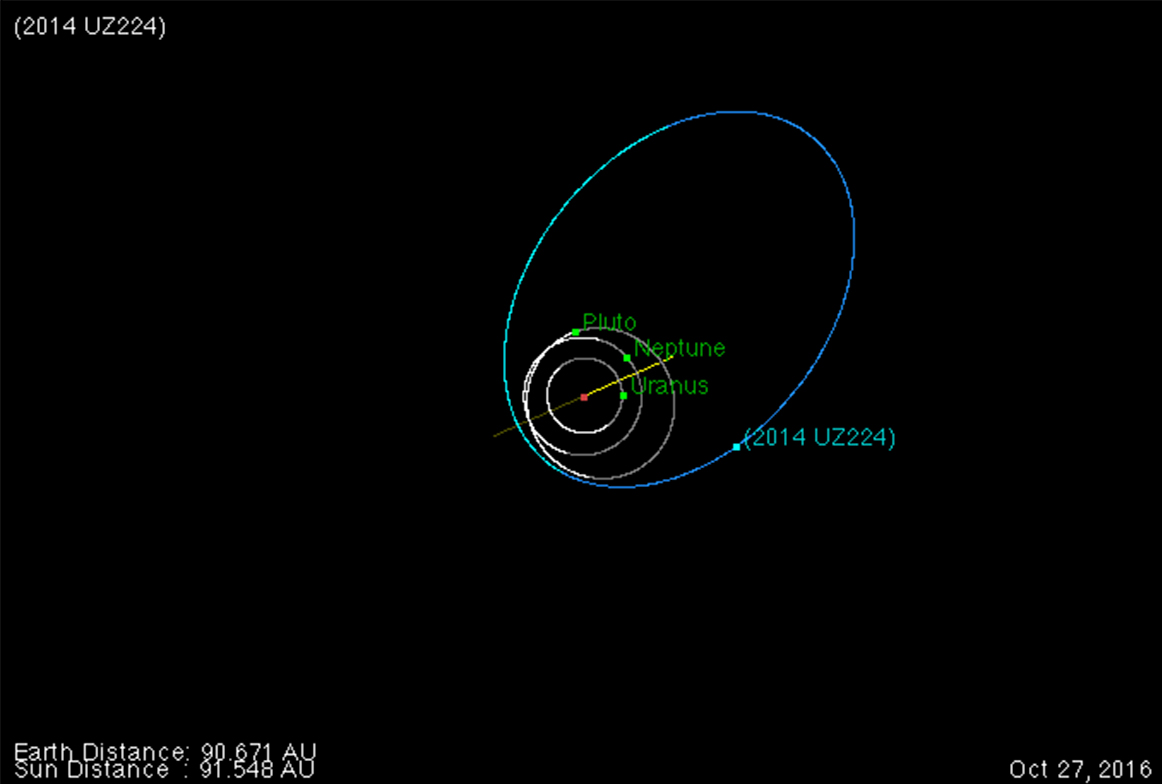

Along with colleagues from the University of Michigan, Fermilab, and five Penn undergraduate students, the researchers found a dwarf planet candidate—called 2014 UZ224 and nicknamed DeeDee—around 8.6 billion miles from the sun. The planet is currently three times as far from the sun as Neptune and the second-farthest object (with a known orbit) in the solar system after dwarf planet Eris, which is 8.9 billion miles from the sun.

The discovery was a happy accident, what Bernstein calls a “fringe benefit” of the Dark Energy Survey, a project that has so far resulted in 44,000 highly detailed images of the sky. The investigation initially aimed to confirm dark energy as one way to explain the acceleration of the universe’s expansion. But pictures of large swaths of sky are bound to reveal other hidden treasures.

“Stars are always in the same arrangement; they are fixed,” Bernstein explains. But, he says, “something moving around the sun will appear to move among the stars.” If an individual were to compare two images of the sky weeks or even years apart and found an object in one but not the other, more than likely it’s not a star.

Sako adapted some of the survey’s software to essentially subtract one image’s content from another, giving the researchers a list of dots to examine further.

“It’s not immediately obvious that a dot in this place one night and in some other place a year later are the same thing moving through the solar system,” Bernstein says. “There’s the find-the-dots step and the connect-the-dots step.”

Thanks to 17th century physics, astronomers know how to predict a planet’s orbit. For three dots suspected of being the same, single object, they can pinpoint where dot four should appear. The more numerous the accurately predicted dots, the more confidence about a scientific discovery.

As for DeeDee, it remains a dwarf planet candidate until confirmation of its shape. If it is round—meaning it has strong enough gravity to prevent tall mountains from forming—it becomes an official dwarf planet, like Pluto, and gets an official name. Given its size and brightness, Sako and Bernstein suspect this is the case, but will know more after further analysis. If the new planet isn’t round, it is a minor planet.

Regardless of the final outcome, DeeDee is still one of the farthest known objects in the solar system.

“Given the enormous amount of Dark Energy Survey data with tens of millions, maybe hundreds of millions of dots in the sky, that we can actually identify four or five associated with a single thing, that’s amazing,” Sako says. “The technology is cool.”

And, adds Bernstein, it’s another step toward learning about our solar system’s origins and finding a ninth planet the research community hypothesizes could be 10 times Earth’s mass.

“These are relics of the very early solar system, undisturbed,” Bernstein says. “It’s like digging up a fossil from 4.5 billion years ago.”