Urbanization and the Influence of Poor Migrants on Politics

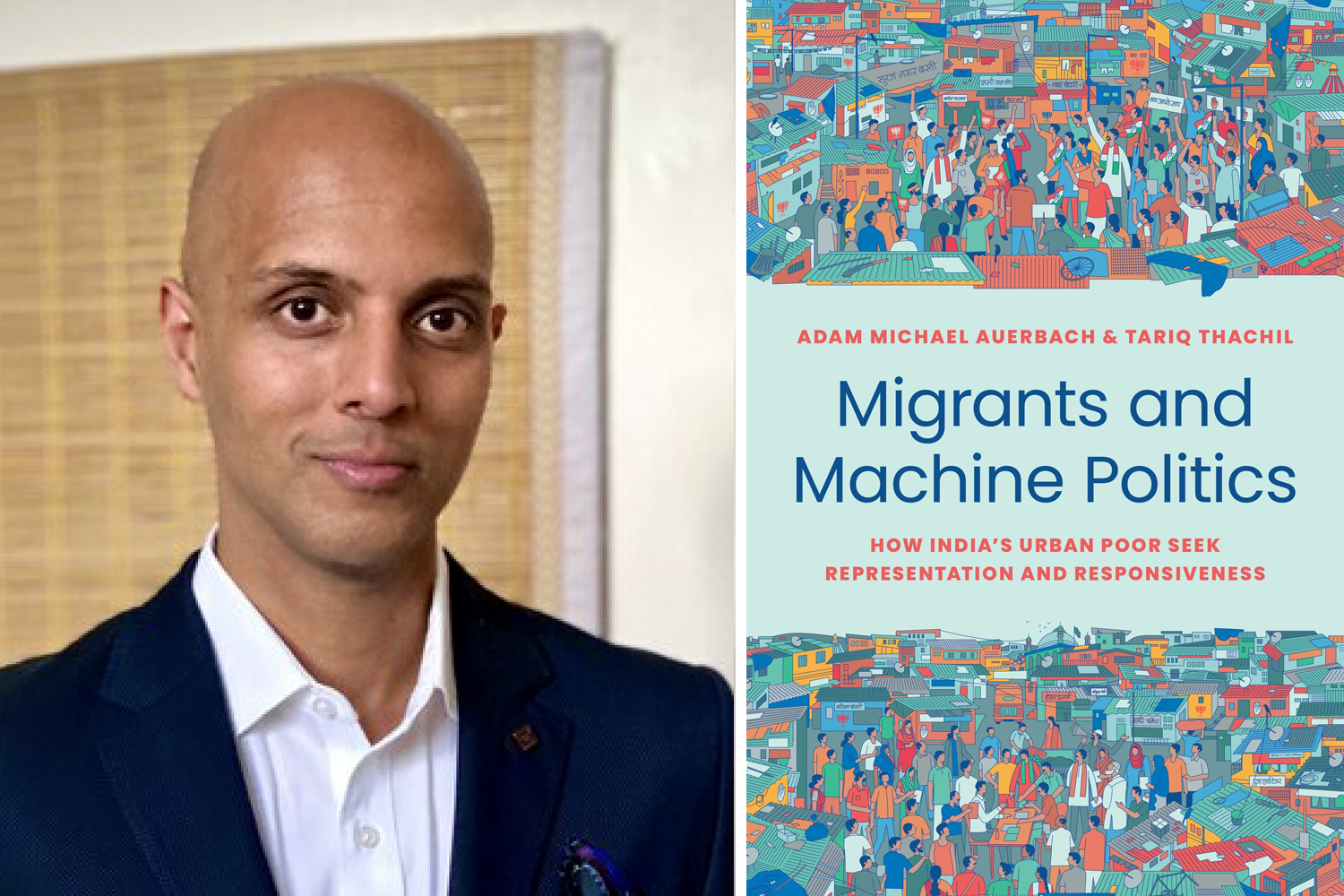

A new book from Professor of Political Science Tariq Thachil explores how the most vulnerable individuals in India are making a political impact.

Over the next 30 years, India is expected to add approximately 400 million people to its cities—the largest expansion in the world by far—with many of them coming from rural areas and with scarce resources. Currently, more than 50 of the country’s cities are home to more than a million people each. There’s little question that during such large-scale urbanization, these migrants are shaping city politics, but Professor of Political Science Tariq Thachil and Adam Michael Auerbach of American University wanted to understand how.

It’s the topic they tackle in their new book, Migrants and Machine Politics: How India’s Urban Poor Seek Representation and Responsiveness.

“In many wealthy, Western democracies, urbanization preceded full democratization. In India, everyone got the right to vote in 1947 when the country was more than 80 percent rural. The impetus for this book was the desire to know what happens when democracy proceeds urbanization and how poor migrants get integrated into city politics,” explains Thachil, who is also director of the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI) at Penn.

Drawing on years of fieldwork, including ethnographic observation, interviews, surveys, and experiments, Thachil and Auerbach found that poor migrants in India’s slums are actively shaping urban politics and doing so in counterintuitive ways.

“There’s a popular portrayal of slum dwellers as completely subdued and dispossessed, living under the coercion of local strong men and city elites, or exploited by cunning politicians who make empty promises,” Thachil says. “We quickly found that those narratives didn’t square with a much more nuanced reality. Instead, migrants in these settlements are very politically aware, informed, and organized.”

For example, Thachil witnessed intense political competition, including residents holding informal community elections to select their local leaders. One, which had official rules and paper ballots, even engaged the local police to oversee the ballot counting. “It mimicked the rituals of formal elections in India,” Thachil says. “This illustrates a much more popular democratic competitive politics than popular portrayals have suggested.”

Another common misconception of slum residents, Thachil adds, is that they prioritize shared ethnicity, caste, faith, or political party when making representative selections. Although those factors do matter, the researchers discovered that what matters most for residents is who will most effectively make change.

“We found evidence that the residents who are most likely to succeed in leadership positions are highly educated or who have jobs that place them in proximity to government bureaucracy so that they have the kind of ‘know how’ to get water connections or apply for welfare, for example,” he says. “In some ways it’s more meritocratic than politics in wealthier settings in India. You have to earn your stripes as a slum leader and that has upstream implications for city politics because those local leaders then get absorbed into political parties.”

The book delves further into those implications, examining how political parties assess and decide which slum leaders to incorporate into their political networks, in part because they want to deliver votes from within the dense slums. “In this way, slum residents—who are otherwise vulnerable and dispossessed—actually have choices that aggregate to produce particular leaders,” Thachil says, adding that these people then become part of mainstream politics, sometimes holding crucial positions in those parties. “This becomes a way for democracy to work from the bottom up in a system that’s usually very top down,” Thachil says.

He stresses that this more nuanced understanding of this group’s influence on politics is not meant to romanticize or celebrate the difficult conditions in which they reside. “It’s often because of how difficult those conditions are that they’ve had to be organized to fight against things like eviction efforts, because they live in insecure housing and don’t have property rights, or to gain access to public services like water or electricity,” he explains.

With this book, Thachil says he hopes that by emphasizing the potential of urbanization for poor migrants in India, he has been able to demonstrate that the most vulnerable can participate in city politics in a meaningful way. “There are famous theories that predict that urbanization will unlock economic development and more socially open or tolerant environments,” he says, “but for places like India, a lot of that potential hinges on how poor migrants are woven into cities and the degree to which they are integrated or excluded.”

Continuing his research in India, Thachil is currently working with Auerbach on a project looking at governance challenges in small towns in the state of Rajasthan, in northern India. He is also working with CASI postdoctoral research fellow Shikhar Singh to study air pollution in Delhi, probing why such a chronic problem has not yet become an electorally salient issue.