Inequalities Deepen When Social Progress Tied to Private Interests

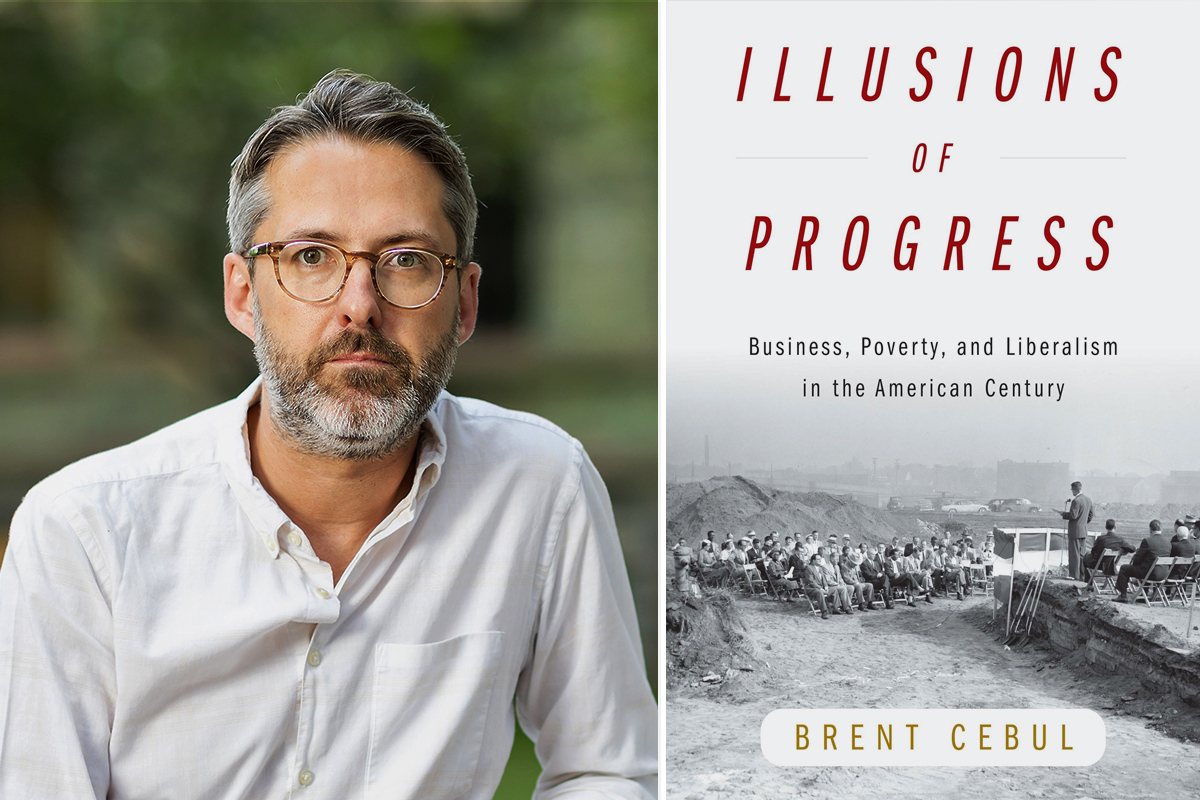

In his new book, Assistant Professor Brent Cebul explores the history of public-private partnerships to rethink how liberalism has served businesses over underprivileged people.

As a kid, Brent Cebul was a sports fan in suburban Cleveland, captivated by the city’s construction of the first major sports stadium in almost 60 years. He even assembled his own model of Jacobs Field, the home of Cleveland’s baseball team beginning in 1994.

Cleveland’s renewal, fueled by publicly funded stadiums, prompted national media outlets to flaunt it as the epitome of American cities returning to prominence. “But then,” Cebul says, “I would be driving from my comfortable suburban community through most of the city and saying, ‘This doesn’t seem to be trickling down.’”

This stuck with Cebul, an assistant professor in the Department of History. He wanted to know why these narratives of progress and growth didn’t always play out as promised: There was an urban revival, but not for everyone.

It’s a thread that led Cebul to his first book, Illusions of Progress: Business, Poverty, and Liberalism in the American Century, which published in March. Cebul studied his hometown of Cleveland and Rome, Georgia, from the 1930s through the 1990s, to look at how, in two very different places, liberalism sought to structure markets and use businesses to accomplish social initiatives through public-private partnerships—often at the expense of the underprivileged people who were supposed to benefit.

“These logics played out in largely the same way in very different areas, and the common throughline there is the federal policy and federalism itself as a constitutional structure,” says Cebul, who is interested in urban history and the inequalities that have persisted because of policymaking. “This isn’t a Southern model. This isn’t a Northern model. This is a federal, local, public-private model that ends up looking structurally very similar everywhere.”

Cebul coined this model “supply-side liberalism.” He meant it as a way to describe how the government would rather influence markets to achieve social progress than work toward the social progress itself.

In the book, Cebul focuses on the shortcomings of public-private partnerships in solving poverty during the 20th century. A compelling dynamic emerged in his two concurrent case studies.

This isn’t a Southern model. This isn’t a Northern model. This is a federal, local, public-private model that ends up looking structurally very similar everywhere.

“We’ve thrown an awful lot of money and resources and tax benefits at the private sector to do things like deliver affordable housing or provide a jobs program for poor people or incentivize community centers,” Cebul says. “Often what ends up happening is that businesses find a way to turn this into a profit motive first and whatever social benefit trickles down is far more meager.” The programs are called into question only when the underserved people who were supposed to have been benefiting realize it’s not happening.

A maddening cycle follows, according to Cebul. When those programs fail to deliver the social benefits they promised, the inclination is to blame the state. A public program is scrapped and even less regulation on corporations follows. “We all of a sudden need to bring the private sector back in to manage community development again,” Cebul says.

The large, subsidized labor programs that started in the 1930s self-consciously did not create national bureaucracies; instead, Cebul believes, they extended the faith that local elites could act in the broader interests of the community. He sees parallels to the current political dynamic: The Biden administration has made certain types of investments safe for private capital through various banking mechanisms. It’s an old model, Cebul says, just with the backing of a huge amount of federal dollars.

“We’re recreating the system of a publicly secured, private-profit system without guaranteeing downstream social benefits for regular people,” Cebul says. “So, we may get the green transition and we’ll probably get it in some form or fashion, but it may be less efficient and consumers may have less purchasing power because we haven’t supported the creation of unionized jobs. Had there been a little bit more meat on the regulatory bone, you might get more of that.”

As Illusions of Progress reveals, that pattern is seen for as long as these public-private partnerships have existed.