We, the People

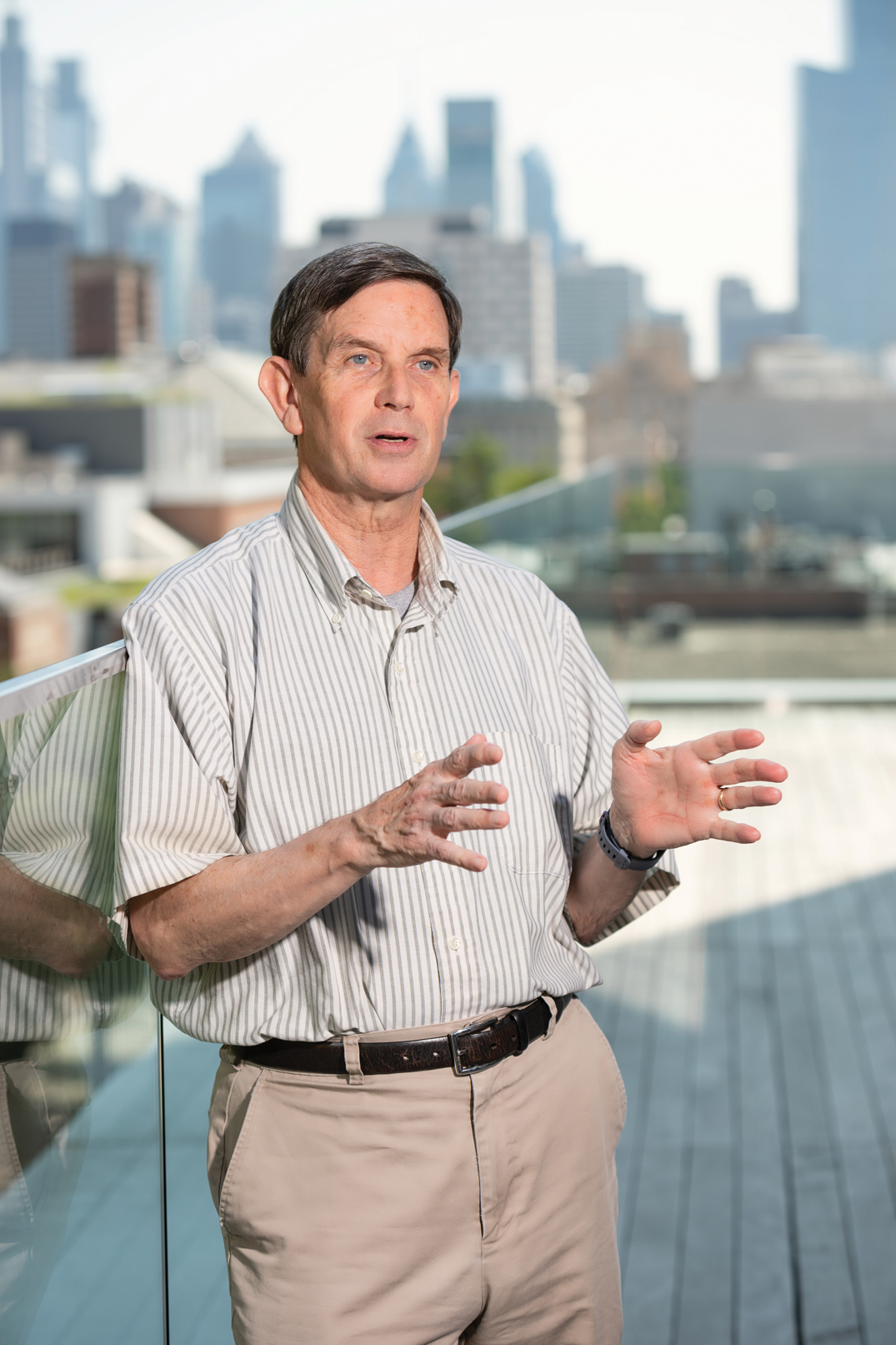

Rogers Smith, Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Political Science, is searching for the heart and soul of America.

As a young man with political ambitions, Rogers Smith wanted to do big things. He never envisioned himself becoming an “academic scribbler.” But today, Smith is the Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Political Science and—as the author of eight books and scores of major essays on American political ideology, civil rights, and constitutionalism—quite the scribbler. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Academy of Political and Social Science, and the American Philosophical Society.

As a scholar, Smith is perhaps best known for challenging the view that the U.S. is fundamentally, “in its heart and soul,” a liberal democracy. “Everyone accepts the universal principles of human rights and democracy as our true principles,” says Smith. “Those are powerful American traditions, but I have stressed in my writing that they don’t constitute the essential nature of America. There isn’t an essential nature of America. America is a product of ongoing political contestation and struggle.”

This argument was central to Smith’s most cited work, his 1997 book, Civic Ideals: Conflicting Visions of Citizenship in U.S. History, which received six best book prizes and was a finalist for the 1998 Pulitzer Prize in History.

It is a somewhat guarded view for someone who calls himself an optimist, but it comes from decades spent examining the country’s policies, laws, and political movements against the backdrop of its founding doctrines.

A POLITICAL SCIENTIST IN THE MAKING

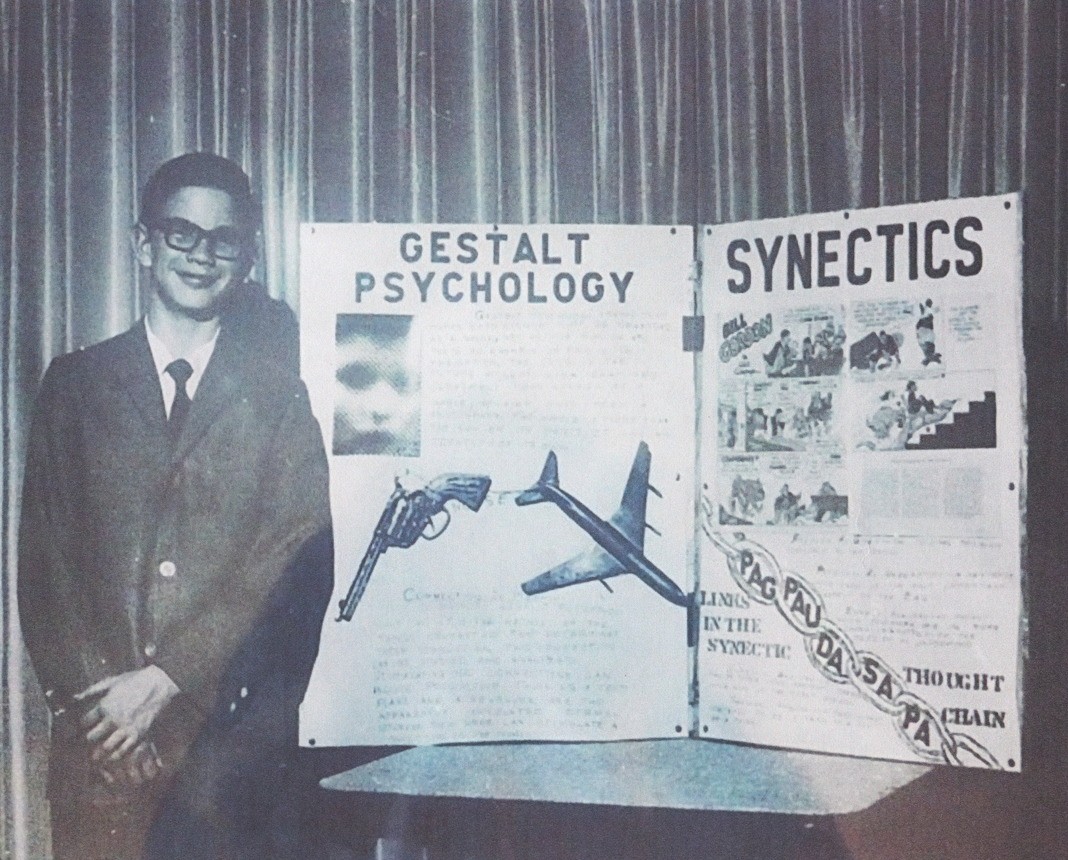

Smith spent his teen years as an activist with the Republican party in his hometown of Springfield, Illinois, eventually rising to state chairman of the Illinois Teenage Republican Federation. Springfield is, of course, the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln and the state capital. Politics was in the air.

“Although no one in my family had been involved in politics, my family talked a lot about contemporary issues,” he says. “My father was a conservative Republican businessman, and so I thought of myself as a conservative Republican, too.”

Illinois State Science Fair, 1967

Courtesy of Rogers Smith

Smith attended the James Madison College at Michigan State University, which offered a small liberal-arts-college experience within the larger university and had a curriculum focused on political philosophy and history. The classes introduced Smith to a life of ideas. “I found that I actually liked scholarship better than politics,” he says.

Besides, Smith’s youthful foray into politics had left him profoundly disillusioned—both with the corruption that was then rampant in Illinois politics and with what he perceived as increasingly racist attitudes among his fellow GOP activists.

“I had thought of myself as an Abraham Lincoln Republican,” he says. “I thought we were the party of civil rights. I decided I couldn’t be part of the Republican Party anymore. I had to step back and ask myself: What do I really believe in? What am I really for and why?”

Smith began to immerse himself in constitutional law as a graduate student at Harvard. His dissertation, Liberalism in American Constitutional Law, also the title of his first book, laid out the issues that would concern him throughout his career—questions of citizenship, identity, and political community. “I was interested in finding a way to connect political principle and purpose with American political controversies that were so motivating for me.”

QUESTIONS OF EQUITY AND BELONGING

Among the controversies that have motivated Smith is the problem of systemic racism. While some see the election of Barack Obama as evidence that the U.S. has left its racial divisions behind, this summer’s civil unrest in response to the deaths of unarmed Black people at the hands of police has highlighted the fact that racial inequality remains a highly volatile issue in the political landscape.

There isn't an essential nature of America. America is a product of ongoing political contestation and struggle.

Smith’s 2011 book, Still a House Divided: Race and Politics in Obama’s America (written with Desmond S. King, of the University of Oxford), explores Obama’s legacy. Smith calls Obama’s election a historic event, but perhaps not a world-changing one. “He is the first and only person of modern African descent to be elected leader of a primarily European-descended country,” says Smith. “Given that the European imperial expansion is ultimately responsible for doctrines of race and racial inequality, his election was a world-historic event, a big breakthrough.”

Ultimately, though, Smith says the Obama administration did not explicitly address racial inequity in any significant way. “He didn’t think he could afford, politically, to do that.”

Smith has long warned that racial conceptions of American identity could resurge. “A lot of people said that couldn’t happen,” he says. “Unfortunately, it has happened. I don’t take pleasure in that—I’m horrified by it. But I do think I contributed to an understanding of how it could happen and how to address it.”

The election of Donald Trump, W’68, in 2016 brought arguments over American racial identity to the fore. Smith explains, “There is a deep sense on the part of many white Americans, especially white older Americans, that they are losing their country. And they’re not wrong. They are—we are—losing a kind of privileged status that we’ve had through most of U.S. history, the privileged status in which your ideas and interests are considered first and foremost in the operations and policies of every American institution.”

He says the fact that voices of underrepresented groups are gaining prominence is unsettling for many people, but he hopes that people can be brought to recognize that a more equitable country would benefit everyone. “If they are citizens of a thriving multiracial democracy with liberty and justice for all,” he says, “that’s better than being perched with a sense of insecurity atop a racial hierarchy that is in many ways unjustly constructed.”

It’s important to make people see that they’re included in, and can partner in, advancing those traditions that represent the better angels of our nature.

Smith argues that any new policy should be assessed in terms of its potential effect, positive or negative, on racial inequities. He and co-author Philip A. Klinkner, of Hamilton College, promoted this idea in their book, The Unsteady March: The Rise and Decline of Racial Equality in America. Smith envisions this standard being adopted by a “racial reparations policy alliance,” but he is not referring to payments to individuals. Instead, he points to innovative efforts to address systemic racism that also advance economic development.

On the national level, a massive infrastructure initiative would be an example of this approach. “Infrastructure broadly defined,” Smith says. “Not just transportation or communication systems, but also energy production, education, health systems. We have deteriorating facilities in many parts of the country in all these areas. This is an enormous burden on the economic future of all Americans.” He says this kind of investment would provide immediate employment opportunities for workers with a range of skill levels. “You can’t address the inequalities that are part of systemic racism unless you address big systems.”

Smith also stresses that addressing inequality does not mean simply condemning people as racist, but rather responding to the sense of grievance that sometimes drives people to embrace racist conceptions. “It’s important to make people see that they’re included in, and can partner in, advancing those traditions that represent the better angels of our nature,” he says.

IN THE CLASSROOM

Smith came to Penn in 2001 after 20 years on the faculty of Yale, where he held a tenured position as the Alfred Cowles Professor of Government and was co-director of the Yale ISPS Center for the Study of Inequality.

At Penn, his favorite course to teach is an undergraduate class called Race, Ethnicity, and American Constitutional Politics. Smith says many students in the class—often reading primary sources for the first time—had not previously been aware of the ways U.S. policies have worked to preserve systems of white supremacy.

“When you read Stephen Douglas writing against Abraham Lincoln, saying, ‘I believe this nation was built by the white man for the white man,’ then you begin to understand that these are deeply constitutive features of the American political system,” he says.

As a teacher, Smith is committed to making space in the classroom for varying political views.

“My personal history has made me believe strongly that there are decent, intelligent people all across the political spectrum,” he says. “I have always wanted my classes to be venues where people could speak honestly and comfortably about their views. This goal has become absolutely central to my teaching in recent years as the nation’s political polarization has grown.”

In fact, Smith stopped lecturing in the classroom several years ago to allow more time for discussion, posting lectures online. He wants students to think of his classes as “civic assemblies” in which all voices are welcome and students clarify differences as well as find common ground rather than scoring points against those with opposing views.

A few of Smith’s former students have gone into politics, but he is not looking to train political stars. He gets great satisfaction from the fact that many former students have become professors of law or political science.

Smith’s passion for teaching extends beyond the college campus. During his time at Yale, he worked with the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute, a partnership with New Haven public schools designed to strengthen public-school teaching through enrichment courses for teachers.

Bringing the partnership model to Penn, Smith co-founded the Teachers Institute of Philadelphia (TIP) in 2006 and recruited Alan Lee, a veteran public-school teacher and social science scholar, as founding director. TIP offers semester-long seminars taught by Penn professors, Smith included, on topics chosen by participating teachers. Smith served as co-director of TIP’s Advisory Council until 2018 and helped to ensure that the Institute could move forward with a comfortable endowment.

PEOPLEHOOD DEFINED

Three of Smith’s books contain the word “peoplehood” in the title. These include his most recent work, published in spring 2020, called That Is Not Who We Are: Populism and Peoplehood. “It is about the competing conceptions of who Americans are and should be as a people,” he says, “and how we can encourage people to embrace more inclusive, egalitarian conceptions of our common peoplehood.”

Peoplehood refers to a variety of political communities. “We live in an era where nations and nation-states are the dominant form of political community,” says Smith, “but it’s not the exclusive form of political community and it’s not the only historical form of political community.”

Smith’s work made him especially well equipped for one of his most significant achievements at Penn, his role as founder of the Andrea Mitchell Center for the Study of Democracy—formerly the Penn Program on Democracy, Citizenship, and Constitutionalism.

“When you create a constitutional democracy, you transform the political identity of its members from subjects to citizens,” Smith says. “I suggested the cumbersome name of Democracy, Citizenship, and Constitutionalism because I wanted to make sure that the citizenship themes would be a big part of the program.”

Smith wrote the original funding proposal and directed the program from 2006 to 2017. The Center was renamed in 2017 after a transformative gift from Andrea Mitchell, CW’67, HON’18, and Alan Greenspan, HON’98. The Mitchell Center offers workshops, lectures, guest speakers, fellowships, research grants, an undergraduate research conference, publications, and other activities. “It’s a Penn success story,” says Smith.

Smith also served as chair of the Department of Political Science from 2003 to 2006 and associate dean of Social Sciences from 2014 to 2018. Outside of Penn, he has held leadership positions with the American Political Science Association, including serving as its president, a platform he used to try to make political science more relevant to civic life through the APSA Task Force on New Partnerships. It aimed to bridge the gap between research- and teaching-focused institutions, as well as address ideological polarization, mistrust of civic institutions, and public skepticism of science and expertise.

THE RIGHTS OF CITIZENS

Smith has written extensively about U.S. citizenship law and historical restrictions on citizenship rights, which he says have often been based on race, ethnicity, or gender. As an advocate of less-restrictive immigration policies, he worries about the resurgence of xenophobic rhetoric around immigration and citizenship. His position on the American tradition of birthright citizenship has sparked controversy among his academic peers—he maintains that the Constitution does not address the birthright status of children of unauthorized immigrants, leaving it a matter for Congress to decide. But Smith has been distressed to see anti-immigrant activists use his theories to advance their policies. (His thinking on this issue was fully explored in the November/December 2018 issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette.)

I think human beings are moved by not just our material experiences of the world, but also by our understandings of the world. And because I believe that, I’ve taken pleasure in both teaching and scholarship.

There are many historical precedents for anti-immigrant policies such as those promoted by Trump, he points out, including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, banning entry to Chinese laborers, and the National Origins Act of 1924, which set quotas on immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and excluded Asians. But the difference is mainly in the rhetoric.

“In those days,” says Smith, “people talked openly about the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race, and we don’t often see that kind of explicit language anymore. Other than that, the arguments today are exactly the same: ‘These new immigrants don’t work hard, they won’t assimilate, they are taking our jobs.’ These arguments were originally used by Benjamin Franklin against Germans and Swedes in the mid-1700s.”

Juxtaposed with rising anti-immigrant fervor, there is today an increased urgency toward addressing systemic racism, and Smith says these two forces represent stark differences over conceptions of civic identity. “Right now, the two [presidential] candidates are offering very different visions of American peoplehood, and it is a time of great division, but I want to think it’s also a time of great promise to move forward.”

One of the most basic rights conferred on American citizens—the right to vote—never universally shared, has been a source of conflict since the nation’s founding. Smith traces this to distrust of a distant, centralized government.

“Creating a strong national government in Philadelphia in 1787 was a highly risky thing to do,” he says, “and so the framers reassured the states by putting elections under state control.”

As a result, American voting systems vary from county to county, creating opportunities for disenfranchisement. Smith calls such a decentralized system extraordinary from a global perspective. In today’s highly partisan atmosphere, voting rights have become a flash point, with Democrats pushing to expand participation and Republicans employing tactics such as purging voter rolls and passing restrictive voter-ID laws. With its Shelby County vs. Holder decision in 2013, the Supreme Court sanctioned these Republican efforts.

THINGS CAN GET BETTER

As a constitutional scholar, Smith worries about what he sees as a breakdown in our system of checks and balances between co-equal branches of government.

“The most fundamental problem in my view is that Congress has not adjusted to the demands of the modern era for a variety of reasons,” he says. “Power is concentrated in the hands of very few leaders. Congress is in session much less than it used to be—they’re spending time fundraising and campaigning.”

Smith used his role as president of APSA to try to improve government, appointing a bipartisan task force of scholars and thinkers to address congressional reform. The task force included experts, both liberal and conservative, from inside and outside the academy, and delivered a report to Congress in 2019.

The recent rise of nationalism in the U.S. and in Europe has caused some political thinkers to question the future viability of liberal democracy. But here again, Smith is fundamentally an optimist.

“I do think there are prospects for building political movements that bring out the best potential of liberal democracy, and in fact extend it further to provide the benefits of our political, economic, and social institutions more broadly,” he says. “There is no certain outcome, but the pendulum is swinging back in that direction, and it’s an opportunity that people need to seize right now. I see some hope for things to get better, and I plan to keep trying to contribute to that in whatever ways I can.”

Smith’s contributions continue. He is at work on a sequel to Civic Ideals. It examined political struggles over American citizenship from the Colonial period through the Progressive era. The new work, Civic Horizons: Pursuing Democratic Citizenship in Modern America, will look at the Progressive era to the present. He and Desmond King are also beginning to formulate another book on racial politics.

Ultimately, Smith is pushing the social sciences to embrace the importance of ideas as opposed to only measuring the material factors that are widely seen as driving forces in political and social life.

“I think that while we clearly are material beings, the way we understand material needs and how they’re properly fulfilled are heavily shaped by our ideas,” he says. “By minimizing ideas in favor of material interests, the social sciences have diminished our capacity to understand human life and human affairs and politics.

“In my own life,” he continues, “because the ideas I grew up with were challenged by real world experiences, I felt compelled to learn, and that led me to change my ideas. I don’t think I am unique in that regard. I think human beings are moved by not just our material experiences of the world, but also by our understandings of the world. And because I believe that, I’ve taken pleasure in both teaching and scholarship—trying to enrich all our understandings of the world, so far as I can. I feel very fortunate I’ve been able to do it.”