Their story reads like a film treatment: Three college students—all politics junkies—meet through their involvement in campus politics and hit it off. From their dorm rooms, they launch a political technology business. Soon after, they are hired to turn around two gubernatorial races in elections where the candidates are underdogs. They not only succeed in flipping the races and getting their candidates elected, they gain prominence as one of the nation’s leading campaign data and analytics firms in the process—all while trying to keep up with their homework.

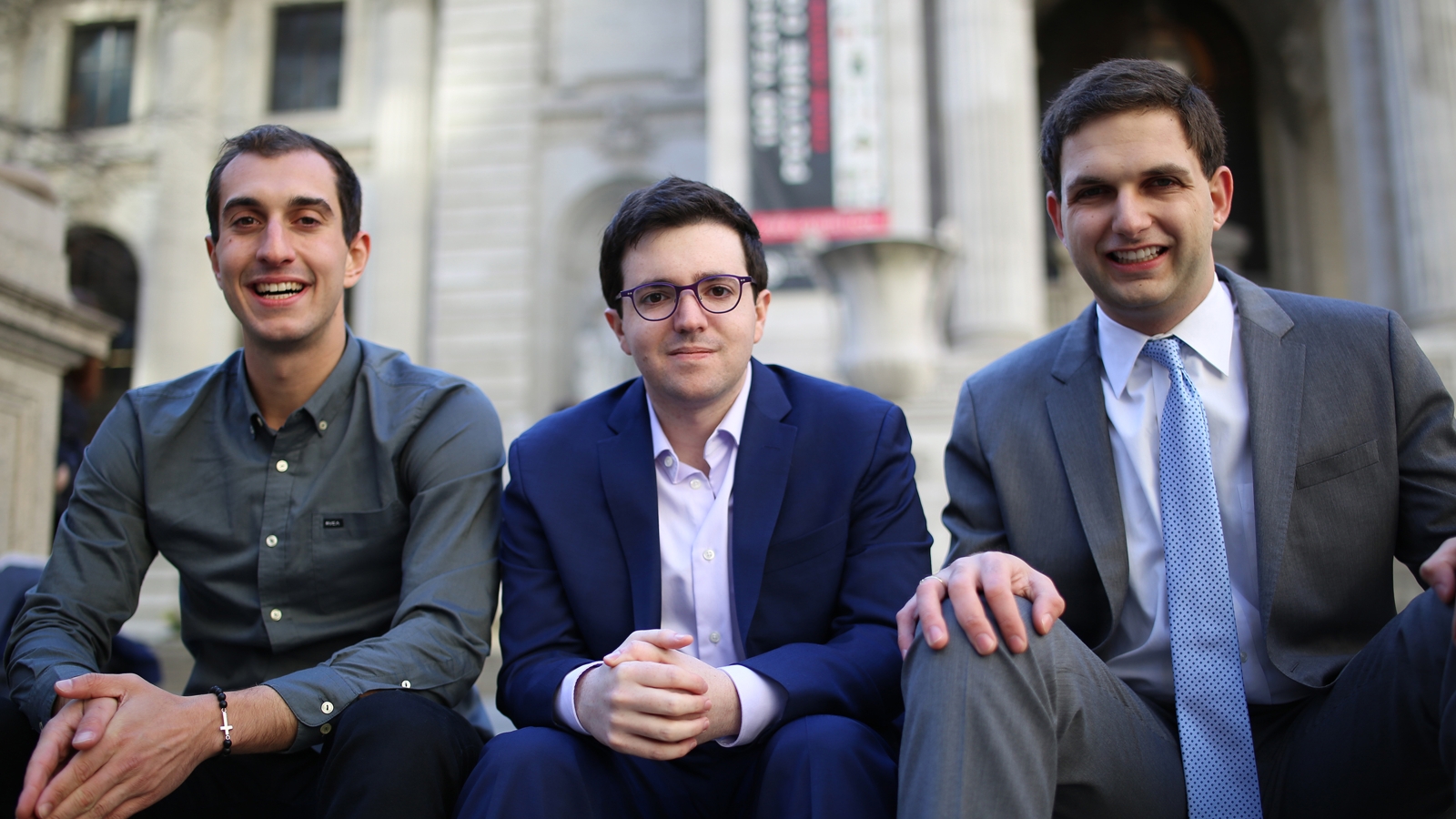

This is, in essence, the true tale of three Penn alumni: Anthony Liveris, C’14, Matthew Kalmans, C’15, G’15, LPS’15, and Sacha Samotin, C’15. Today, the friends are the principals of the political technology firm Applecart, based in Manhattan, and they continue to work their magic on political campaigns. The firm currently consults for campaigns nationwide including the presidential bid of Ohio governor John Kasich. In general, Liveris says, Applecart signs on with clients who are “solutions-oriented governing Republicans.”

The trio’s success is based on a relatively simple concept. Traditional means of mass campaigning—like robocalls, blitzes of TV and radio ads, and yard signs—fail to move the opinions of voters in large numbers. And generic outreach that aims to persuade indistinguishable masses simply isn’t effective, the Applecart founders say. In fact, the only traditional type of campaigning that is consistently, measurably effective for the purpose of mobilizing voters is knocking on doors: person-to-person contact.

“A campaign’s approach to impacting voters needs to be customized to the individual to be successful,” Kalmans says.

All three had worked on political campaigns and had seen both firsthand and in extensive academic literature that conventional means of campaigning just didn’t work. What does motivate voters, they all agree—and the literature confirms—is leveraging personal relationships.

For that reason, from their dorm rooms the Applecart founders sought to invent a process for identifying and leveraging “influencers” in digital and real-world social networks, people at the center of a group who can sway opinions and help motivate friends, family, and coworkers not only to vote, but to support specific candidates. It is this capability that has allowed Kalmans, Liveris, and Samotin to change the conventional wisdom about how to run a successful political campaign at the highest levels of national politics.

Their process is an analog-digital hybrid. It begins with identifying the population of voters relevant to a specific election. The firm works backward to find the influencers among them. To uncover these social networks, they comb through publicly available online and offline records to identify people who went to high school together or who currently go to the same church or play in the same softball league.

“The literature began by identifying neighbors as a vehicle to influence political behavior,” Kalmans explains. “Recognizing that in the 21st century many people simply don’t know their physical neighbors, we expanded on that by building technology to find the friends, bosses, colleagues, and people in communities who can sway the opinions of others in a more significant way.”

At Penn, they crunched the numbers themselves and created a series of algorithms that constructed a web of relationships between voters in a given geography. As the firm has expanded, they have hired engineers and data scientists with backgrounds in Silicon Valley to create a more sophisticated, scalable platform to expand the process nationwide.

“Politics has always been a social activity,” says Samotin. “Every part of the process, with the possible exception of pulling the lever in the voting booth, is social. People watch TV debates with their friends, they talk with their colleagues over water coolers and with their families around the dinner table. It’s fundamentally an interpersonal activity.”

The inspiration for this data-driven, socially focused strategy was twofold. They’d seen how successful the Obama presidential campaigns had been in engaging a digital-savvy electorate using social media, and they wanted to harness that power to benefit their candidates. Kalmans, Liveris, and Samotin were also influenced by the studies they read as research assistants for John DiIulio, Frederic Fox Leadership Professor of Politics, Religion, and Civil Society. In particular, they took interest in a seminal 2008 study by Yale political scientists, theorizing that social pressure to vote is what influences voter turnout the most. Using public records, the Yale researchers mailed letters to thousands of registered voters telling them they would publicize to their neighbors whether or not they had voted in the most recent election. When this social pressure was applied, registered voters responded and showed up to the polls. This idea captured the students’ attention, and they put theory to practice.

They became partners in a new enterprise, a business that would take research about voting and apply it in a real-world context. But they needed start-up capital as well as actual campaigns where they could test out their ideas. After burning through their pooled personal savings—“including our bar mitzvah money,” Kalmans says—they pitched their idea to some potential funders.

“Politics is a cartel. Campaigns do not test the efficacy of their tactics. These operatives certainly weren’t used to a bunch of kids stepping in and asking for tens of thousands of dollars to test out ideas about how big data could reinvent their industry,” says Liveris. “Not one bit.”

First Round Capital, founded by Josh Kopelman, W’93, and located just off Penn’s campus, came to the rescue with its “Dorm Room Fund,” a student-run venture capital fund that gave them a $20,000 grant to get their fledgling operation off the ground.

They were additionally aided by several mentors on campus who helped them make connections. These included DiIulio, who served as a senior advisor to President George W. Bush; Greg Rost, chief of staff to Penn’s president, Amy Gutmann, who had also been chief of staff to former Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell; and David Thornburgh, who served as executive director of Penn’s Fels Institute of Government through 2014.

“We have to give credit to Penn,” says Kalmans. “If we went to any other school, the project wouldn’t have been possible.”

Finally, they got a break. The Republican Governors Association had narrowly lost several winnable races in the 2010 election cycle. The organization was getting nervous about losing several incumbents in the 2014 elections, in particular two governors who were falling behind in the polling leading up to the general election. The association hired Kalmans, Liveris, and Samotin to test their concept in the 2014 primary cycle, as a proof of concept ahead of the general elections of these dark-horse incumbents.

“The primary election was the perfect test tube environment for us,” says Liveris. “There were no competitive races on the ballot and the voters had no reason to turn out, so if we could boost turnout in that race, we could boost turnout anywhere.”

The difference they made shocked them. They produced a 14.6 percent increase in voter turnout, the largest ever recorded in U.S. history as a result of a single intervention.

Six months later, on the night of the general election: “[We] were sitting at Tap House [a Penn watering hole] watching the results come in for the campaigns that had hired us: two underdog governors and two candidates for U.S. Senate. All four of our candidates won their elections,” recalls Samotin. “We were laughing about the fact that we were three undergrads flipping gubernatorial and senatorial elections from our dorm rooms.”

The election wins catapulted the three partners onto the national stage. In the 2016 Republican presidential primaries, they had offers to work on the Bush, Christie, and Kasich campaigns. They chose the last.

“We believe strongly that elimination of mainstream candidates [like Kasich], especially in primaries, puts politicians in office who are less willing to see things from the opposing point of view, and it’s a policy problem at the end of the day,” says Samotin. “This is why Congress is filled with obstructionist politicians who won’t cooperate to pass reasonable legislation, like immigration reform.”

Applecart now has 15 full-time employees in its Manhattan office. They are continuing to work on major elections while also branching out to see if they can apply their model to the corporate world.

“If a person takes a vacation on a cruise ship, you can bet that they come home and talk to their friends about it—and those friends are now the ideal target for the cruise ship company to sell to,” Kalmans says.

Looking back over the friends’ own journey during the past few years, he says, “It’s been a wild ride thus far, but we’ve only gotten started.”