The Striking Parallels Between Trump’s Xenophobia and the Americanization Movement of the 1910s

Tina Irvine, a doctoral candidate in history, authors an op-ed drawing parallels between what she calls Trump’s xenophobia and the nativism of earlier periods.

On the inaugural night of this year’s Republican National Convention, television personality Scott Baio addressed a jubilant crowd, proclaiming that it was “time to make America American again.” This statement, with the insinuation that an authentic America would be a whiter and safer one, had liberal pundits scratching their heads at its brazenness, as well as its vagueness.

Trying to pin down what Baio and the Trump campaign mean by each of their racially charged statements is not the most worthwhile exercise. Almost everyone knows about Trump’s xenophobia, given his penchant for turning to Twitter with inflammatory remarks designed to inspire ire from the left and applause from the right. But fewer people are aware of the striking parallels between Trump’s xenophobia and the nativism of an earlier period.

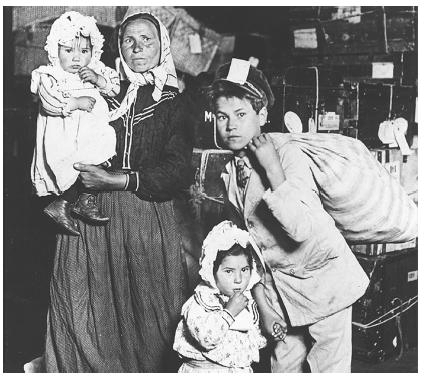

Baio’s comments about the necessity of making “America American again” echo the rhetorical arguments of the diffuse and disjointed Americanization movement of the 1910s and 1920s. This movement was concerned with the cultural integration and assimilation of the thousands of foreign immigrants who came to the United States in the early 1900s. In its earliest years, a loose assemblage of social reformers like Jane Addams, philanthropists like John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, and business leaders such as Henry Ford, carried the movement forward. Through their efforts, which ranged from social settlement homes, to public works programs, to educational initiatives to combat illiteracy and teach democracy, they hoped to instruct immigrants how to be “proper Americans.”

Then, as now, the press and the public hotly contested what it meant to “be an American.” Immigration and border safety were major concerns in the early 20th century, as were social and political threats from foreign radicals. The obvious presence of darker-skinned foreign immigrants—especially those from Southern and Eastern Europe—led many “native Americans” (as white Americans took to calling themselves) to demand nothing less than “America First,” and “100% Americanism.” If immigrants wanted to come to America, they reasoned, they needed to live, act, and think like Americans. They demanded that immigrants learn how to speak English, and that they stop dressing, eating, and acting like foreigners.

Advocates of a more accepting, multicultural approach, like anthropologist Franz Boas, lauded “immigrant gifts,” but this perspective was drowned out after World War I, as pluralist modes of Americanization lost traction and were replaced by those who supported the more rigid conception of loyalty to country.

Above all else, what unites today’s Republican Party and Americanizers of the early 20th century is their reliance on fear tactics and emotional appeals over intellectual arguments. Trump has garnered support through his derogatory comments about Mexicans and their supposed penchants for immorality and drug use. But these emotional ploys are nothing new. In the 1910s and 1920s, fear-mongers took to the “twitter-sphere” of the day—newspaper editorials—and wrote scathing reviews of their present situation by labeling foreigners uniformly criminal, degenerate, and immoral. Taking foreign immigrants and working class African Americans as their primary targets, early 20th century conservatives argued that such people eroded the safety of urban centers and brought moral and social decay to America. Many proclaimed that there was no point in even allowing people who could not be assimilated- by virtue of their race, culture, or politics- into the country.

Trump and his Americanizer antecedents also share common ground in their penchant for labeling and demarcating people based on singular social affiliations. Trump, for instance, caught a great deal of flak for his argument that Mexican-American Judge Gonzalo Curiel could not adequately fulfill his role because of his Mexican heritage, and what Trump assumed was an inherent bias.

The process of lumping and classing of people into social categories has no greater historical parallel than the early 20th century. Jim Crow laws emerged in those years, relegating African Americans to separate spheres for decades. Women gained the right to vote, but “women’s issues” were understood by most men of the time as a separate thing, something that hopefully would soon pass. Instead of radical Islamic terrorists, contemporaries feared Bolsheviks (Socialists) and foreign radicals, whom, they insisted, wanted nothing more than to destroy America through revolution and ideological insurgency.

Like those concerned about the state of America’s “Americanness” in the early 20th century, Trump supporters tend to broadly oppose the current state of affairs rather than support any particular policies or plans to create change. Historian Erica Ryan has argued that Americanism was created in opposition to Bolshevism, and defined largely by what it was not. Trump does something similar whenever he condemns the Obama administration’s decision not to label terrorism in this country as “radical Islamic terrorism,” yet is unable to offer a clear plan of action for how to defeat ISIS. His rhetorically empty and oppositional platform is also similar to the concern voiced by anti-Socialist forces in the first Red Scare of 1919-1921.

For people concerned about the source of radicalism in the early 20th century, branding, rooting, and defining who could be trusted, and who was a cultural and social menace, was of utmost importance. These fears culminated, in many ways, in the now infamous 1924 Johnson-Reed Immigration Act. This xenophobic piece of legislation, which barred Asian immigration entirely and was designed to keep out other immigrants of non-white descent, had lasting effects on this country’s color and culture by limiting the number of immigrants allowed into the United States by using a national origins quota.

Donald Trump’s political success is due in large part to his ability to tap into this wellspring of centuries-old nativism and white supremacist ideology. Trump and early 20th century Americanizers understood the same thing: when people are afraid, they listen—even to empty promises—if it makes them feel safer. The tagline of the first night of the RNC, “make America safe again,” is proof enough of this.

To be clear, the GOP today is not the same as those who identified with the Americanization movement in the 1920s. Despite Trump’s racial insensitivity, he has never advocated—as some Americanizers in the early 20th century did—that immigration be limited only to white people. And, of course, there are many in the party who are embarrassed and troubled by Trump and what he represents. But, whether they like it or not, he is the Republican nominee. What he says, and the policies he supports, will dramatically shape how the party functions in the future, and how we interpret what it means to be an American today. If the past has anything to teach us, it should offer Democrats and Republicans alike a cautionary tale of waving the banner of “100% Americanism.” It would serve us well to think twice about politicians who support policies of social ostracization and fragmentation, increased policing, and race and class divisions in our world today.

This article originally appeared on the History News Network.