To most people, using complete and understandable sentences comes reflexively. But someone with a language disorder called Broca’s aphasia often has trouble producing fluent, grammatically correct speech, forgetting a noun or even speaking words out of order.

Sarah Nam, C’20, Rose Rasty, C’22, and Dori Domi, C’21, had an idea: What if they built an app that could help someone with the disorder communicate more easily? The person could speak a sentence into the phone, and following a series of questions, the app would offer alternative framing structures—all in the person’s own voice. “We thought that could help re-train [the brain] after an injury,” says Nam, from West Chester, Pennsylvania.

The app never came to life, but really, it was never intended to. It was one of eight linguistics moonshot projects created by undergraduates in Assistant Professor in the Department of Linguistics Kathryn Schuler’s fall 2018 Language and the Brain course. Each session covered a different topic—sign language, bilingualism, evolution—to give the students a baseline, and throughout the semester, they also worked on passion projects, following a Google X model to allow for unconstrained thinking about grand problems.

Schuler got the idea after a conversation with Adjunct Associate Professor in the Department of History Bruce Lenthall, Executive Director, and Advisor on Educational Initiatives to the Vice Provost, at the Center for Teaching and Learning. “I was concerned that students with very diverse interests would be taking the class and that they might feel disappointed with just a single lecture on what they were curious about,” she explains. “That’s how the moonshot project was born, to allow students to explore their interests.”

Quickly, ideas began to take shape. There was Nam’s acquired disorders group and one on language and music. Another group wanted to better understand the relationship between internal and external speech. And then there was Matthias Volker’s team, which focused on sign language.

We were thinking really big at first; we wanted to revamp the deaf education system. But as three hearing college students, we knew we weren’t the right people to do that.

“We were thinking really big at first; we wanted to revamp the deaf education system. But as three hearing college students, we knew we weren’t the right people to do that,” says Volker, C’21, from Washington, D.C. Feedback from Jami Fisher, who runs Penn’s American Sign Language (ASL) program, helped the group find a new direction. “We were encouraged to reframe what we were thinking about, from change to support. Instead of reinventing the wheel, she suggested we look at the existing resources out there and how we could be a system of support.”

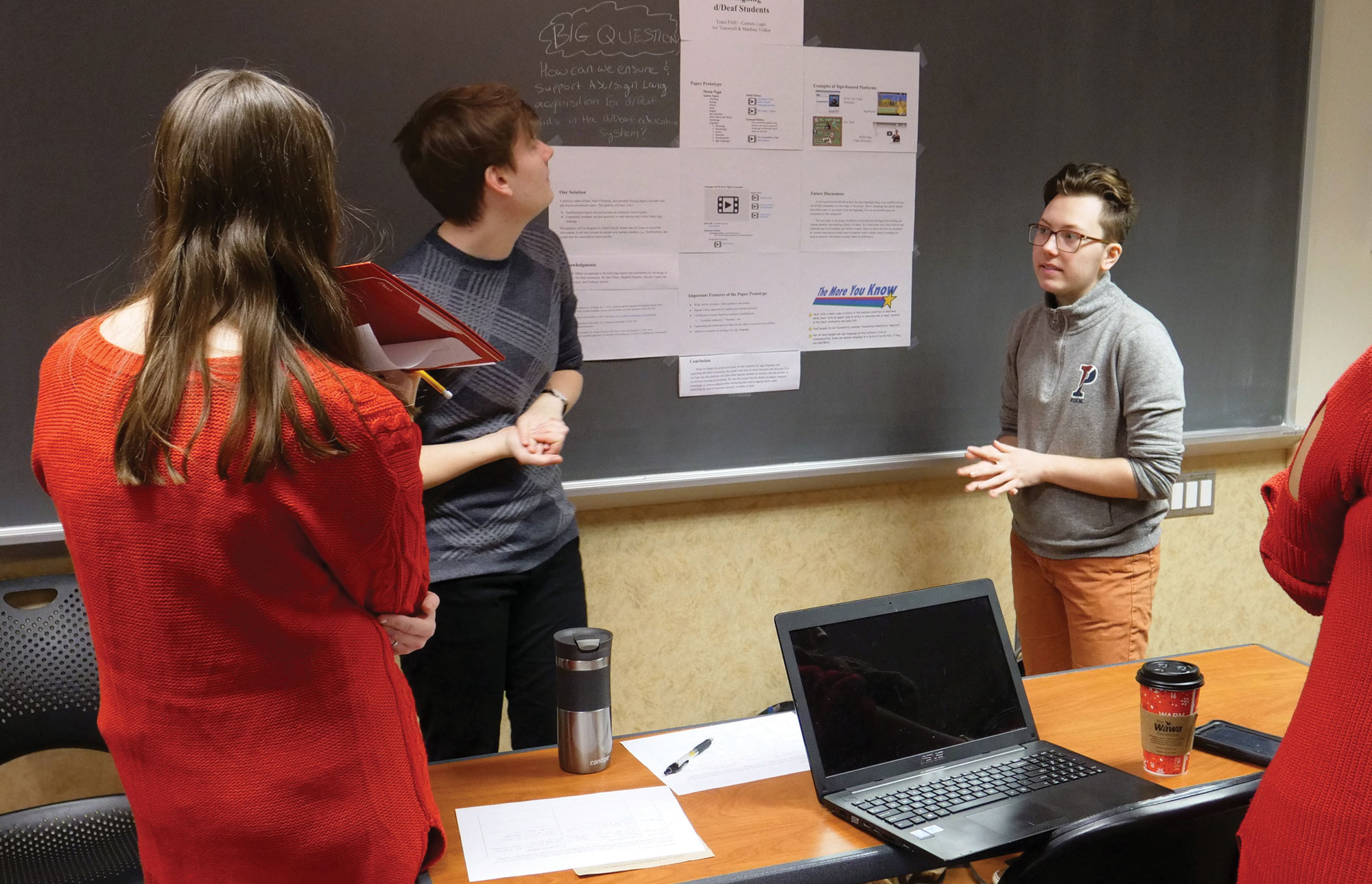

Heeding that advice, the team, which also included Ari Trueswell, C’18, and Carmen Lugo, LPS, ’19, turned its moonshot into an online ASL video-lecture database focused on common middle- and high-school subjects like chemistry, history, and biology. “It reinforces what they’re learning in the classroom but also reinforces their language skills,” Volker says.

It’s the first time Schuler has taught the class, and she was impressed by the students’ dedication and ingenuity. Each week, they posted write-ups on a class blog and provided peer feedback. They pitched their ideas in front of the class and changed course based on recommendations from content experts and their classmates. They dreamed up outside-the-box ideas and weren’t afraid to look foolish.

“The point of the moonshot program at Google X is to allow innovation to happen in a way that’s not constrained,” Schuler says. “The real innovation usually comes when it’s a crazy idea. To have an outlet to pursue a few of those is useful.” Of course, this was a college course with a grade endpoint, not a real-world product susceptible to business critiques and economic whims. But the underlying notion remains true: Offering the 30 students a chance to think big about big problems led to imaginative and clever solutions.

“There was a lot of freedom,” Nam says. “We were encouraged to think for ourselves and think with each other. It wasn’t just a professor feeding us information. It really changed the way I approach my learning in general.”

Nam says she and her classmates don’t currently have plans to take the app further than the template they created for Schuler. Neither does the sign language team. And though Schuler admits it would be “super cool” if any of them decided to continue work on the projects, her goal was, of course, to offer a positive learning experience. “This is a useful avenue for students because it helps lessen that fear of failure,” she says. “If an idea is not great, it’s not great. But maybe it’ll be cool—and maybe it will help you become a little more unconstrained in your thoughts.”