Seeing Clearly Through the Fog of War

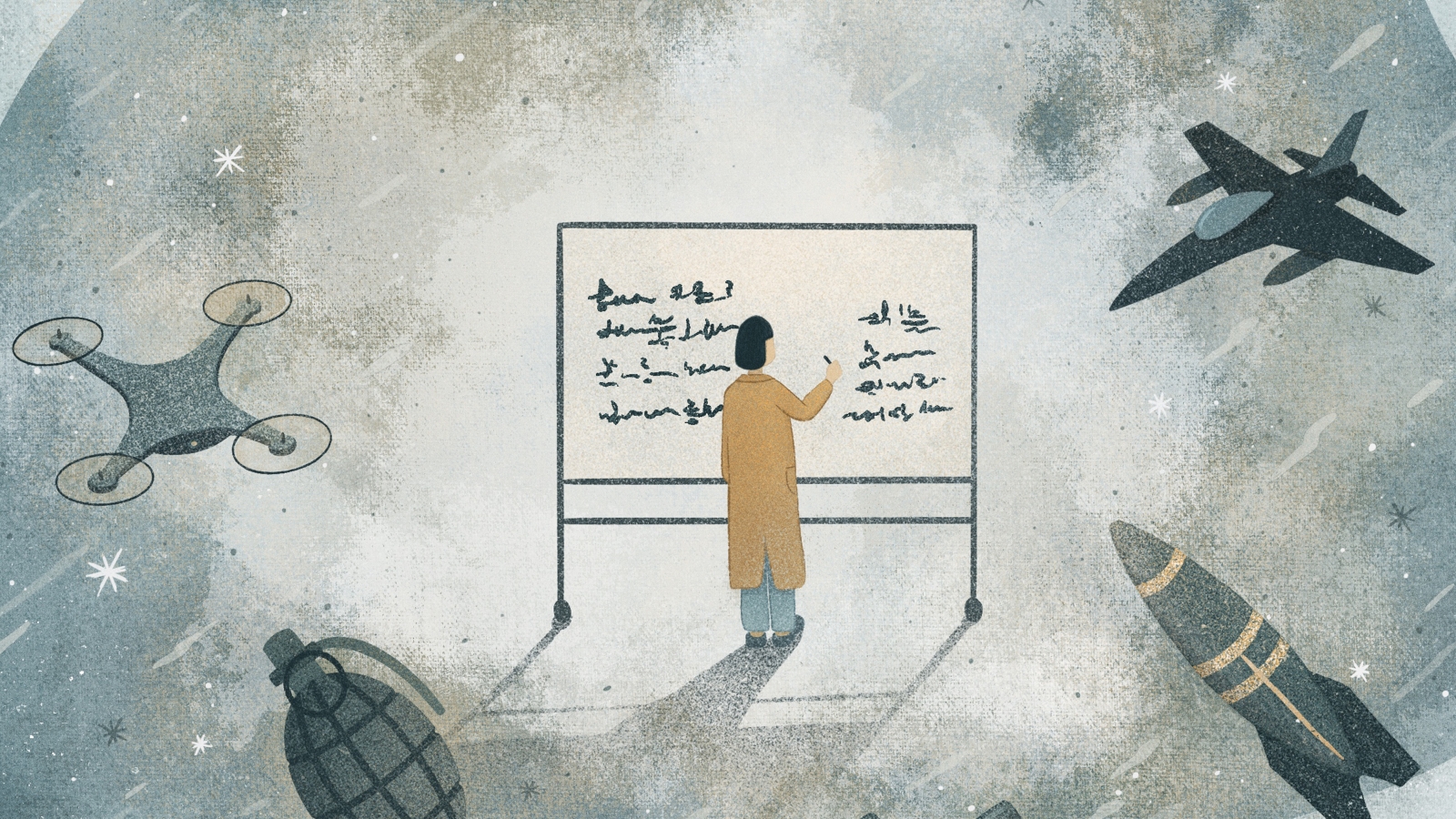

In a new book, M. Susan Lindee, Janice and Julian Bers Professor of History and Sociology of Science, explores the interplay between scientific progress and violence in modern war.

Scientific advances can both heal and harm. The discoveries that underlie technologies from the gun to the atomic bomb emerged from the minds of scientists. Consequently, the creators of those and many other technologies have found themselves in moral quandaries resulting from the violent application of their insights.

In a new book, Rational Fog: Science and Technology in Modern Warfare, M. Susan Lindee, Janice and Julian Bers Professor of the History and Sociology of Science, explores how science and scientists have engaged in the advancement of military might.

In nine chapters that span from the invention of guns in the Middle Ages to the emergence of drone warfare, she charts the nuanced moral terrain scientists have walked in developing these technologies. Without labeling the work itself as moral or immoral, Lindee notes how some researchers embraced the implications of their studies and innovations, while others distanced themselves from the consequences.

The book’s title—a play on the “fog of war”—relates to the valorization of rationality among scientists.

“When Carl von Clausewitz, a Prussian military analyst, talks about the fog of war,” says Lindee, “he means that the view of a commander moving into a battlefield is obstructed, that the situation is uncertain and unpredictable. My title extends this idea to technical experts. The fog is a moral and ethical fog. They’re moving forward, trying to make decisions about what questions to pursue and technologies to produce, often doing so without foresight, reflection, or overt ethics.”

The book emerged from Lindee’s teaching—specifically the course Science, Technology, and War—and her investigations into the moral crises some scientists faced and considerations of what the flashpoints for science’s application in violence may be in years to come. “My own research has been about the atomic bomb and the Cold War, and how geneticists and biological scientists navigated this era, how they reacted to the idea that military interests could shape their interests,” she says. “I got interested in the bigger theme and the more personal theme: How do individuals navigate these complex and morally vexing circumstances?”

Lindee explores the role of universities in the waging of war, including creating new knowledge for national defense organizations. “There is not any scientific field that did not at some point get pulled into defense interests in the course of the 20th century,” she says. At the same time, she notes that war has spawned new scientific knowledge.

She also points to major moral quandaries on the horizon.

“The brutal stuff that’s coming are drones and cyberwar,” Lindee says. “Cyberwar is now where significant funding is going. But there are also equally scary efforts aimed at intrusion into corporate networks, disruption of banking systems, having an impact on water purification systems, or, most recently, disrupting the cold chain for the new coronavirus vaccine. These are nightmare scenarios.”

Drones are somewhat different, she explains, as they remove a natural brake on military action. “Individuals can and do sometimes refuse to fight; soldiers can shoot their guns above people’s heads, they can desert, they can protest—all forms of resistance. All through the history of warfare, in order to have an effective army, it has been necessary for states to persuade relatively large numbers of people to fight. Military theorists propose that the robot or the drone eliminates the risks to individual soldiers, but the risks to individual soldiers are part of what puts a brake on violence.”

There’s an inherent critique in Rational Fog.

“What if we turned knowledge to human needs and human benefits instead?” Lindee asks. “One of my friends says the book is subversively pacifist. Maybe that’s true.”