March 2020 marked the beginning of a sweeping, uncontrolled experiment. Across the country, millions of people attended school and did their jobs from home, minimized their interactions in the world, and conscribed their social activities throughout months of COVID quarantine. The experience left many of us pondering the power of connection and the impact of its absence.

Today, from the relative normality of 2023, we collectively continue to process the disruptions of quarantine through books, articles, and podcasts, as well as scientific research, probing our social nature. What do we miss when we can’t be together in person? What do we need from other people, and from our communities? What’s the value of being social?

On February 1, 2023, five faculty associated with MindCORE shared their observations on this theme with an audience of more than 150 alums at Slate NYC. MindCORE, or the Mind Center for Outreach, Research, and Education, is a Penn Arts & Sciences hub for researchers across the University studying human intelligence and behavior. Watch video of the full talks below:

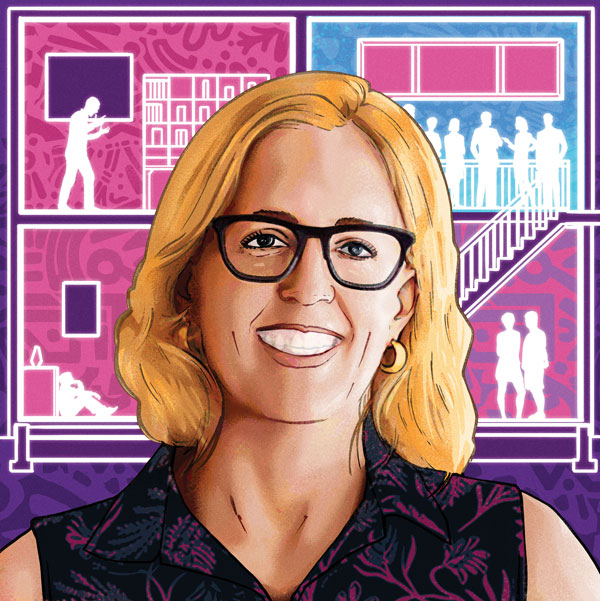

Panelists delivered short talks around the theme of sociality from the perspectives of their own research, and the consensus was clear: We are fundamentally social animals, from the wiring of our brains to the structure of our social networks. Connections are critical not just to our happiness but to our survival.

As Michael Platt, the evening’s first speaker and the James S. Riepe University Professor, put it, “People who have more friends or deeper friendships live longer, healthier, happier lives, and they make more money. And the flip side is true: Chronic loneliness is more devastating to your health and well-being than smoking a pack of cigarettes a day.”

What follows are observations from the evening’s presenters, sharing what their research has to say about the nature of connection and its importance to us.

Michael Platt: Examining the Social Brain

As Michael Platt observes, social connections have an indisputable impact on our capacity to thrive. The bigger mystery is the underlying mechanism, or “how the social environment gets under our skin to affect our health, wellness, and well-being.”

A professor of neuroscience, psychology, and marketing with appointments in Penn Arts & Sciences, Wharton, and the Perelman School of Medicine, Platt examines questions ranging from how people make decisions, explore, learn, and form connections to how to use new knowledge about the brain’s mechanisms to improve health and well-being and maximize human potential.

“Our brains are wired to connect,” says Platt—and he means this literally. Structures in the brain, collectively described as the “social brain network,” work to manage our moment-to-moment interactions with other people. He notes that in individuals who have more friends, the social brain network is larger—a finding documented in an April 2022 Science Advances paper involving rhesus macaques. This study looked at a two-pronged brain circuit in macaques that functions identically in both the monkeys and humans to govern empathy and relationships.

Platt notes that humans aren’t unique in having a social brain. What does make us unique, in his estimation, is that the sociality dial in humans is “turned up to 11.” But some questions are difficult to study directly in humans, and so, given how similar the human brain and genome are to that of monkeys, they are a valuable model for understanding human behavior.

People who have more friends or deeper friendships live longer, healthier, happier lives, and they make more money. And the flip side is true: Chronic loneliness is more devastating to your health and well-being than smoking a pack of cigarettes a day.

This is why Platt and his colleagues have spent the past 17 years studying a population of about 1,700 rhesus macaques on Cayo Santiago, an island off the coast of Puerto Rico. The team had been documenting the monkeys’ behavior, social connections, genetics, biology, and brains for years. Then came Hurricane Maria, a natural disaster that completely altered the monkeys’ habitat.

The physiological stresses of the event clearly accelerated aging in many of the monkeys. Following the hurricane, the animals also formed closer social connections. What the researchers saw is that “the monkeys who actually managed to make more friends were more likely to survive, and their babies were more likely to survive,” says Platt. “The survival value of being social was made very clear in the aftermath of Maria.”

Platt says that humans share this tendency to seek connection in reaction to disasters. But with the monkeys, he says, “what’s miraculous is, they’ve sustained this for five years … and we see no signs of letting up.”

Rebecca Waller: On Being Antisocial

“The word psychopath never fails to elicit a reaction,” asserts Rebecca Waller. It is, she explains, a concept often framed by its extremes, real and fictional—from Jeffrey Dahmer to Hannibal Lecter.

As Waller sees it, to better understand ourselves as social beings, it’s valuable to come at the problem from the opposite angle: understanding the antisocial among us. An assistant professor of psychology who studies the developmental influences on social behavior, she has a particular interest in antisocial behaviors like aggression and callousness.

Waller defines psychopaths as “fundamentally antisocial people who are characterized by this lack of empathy, a lack of guilt, and who are able to lie, and cheat, and manipulate other people to get what they want, even at great cost to other people.” These traits can play out in the violence and crime frequently associated with psychopathy. But they can also play out in much more mundane ways, “in people we interact with who are antagonistic, who are coercive, who are manipulative.” Some people, she notes, might even associate some advantages with psychopathic traits: for example, “the idea of a successful psychopath, someone who can perhaps leverage that fearlessness, that deceitfulness to get ahead in life, to get their company in a better position, maybe even their country.”

In her lab, Waller works to understand the continuum of psychopathic and antisocial traits and behaviors, considering all age groups. A major focus of her work is to identify what psychopathy looks like in young children, something she seeks to do by measuring personality, temperament, and behavioral characteristics that might eventually manifest as psychopathy in an adult. “We look at really early difficulties children have with empathy, lack of guilt, and recognizing and responding to social and emotional cues from other people,” Waller explains. They also look at factors in the environment: home life, school life, and community.

“This work on being antisocial can tell us a lot about what it means to be social, to be cooperative, to be empathic,” she says. Another important aspect of her work is providing a basis for clinical interventions. “How can we use this,” she asks, “to, in a non-stigmatizing way, identify children much earlier, and direct services and intervention and prevention efforts so that we can reduce risk of harmful outcomes?” Such interventions can have broader impacts, she notes, addressing “the great costs of violence and crime at a societal level, as well as in our daily interpersonal interactions with other people.”

Brain Teaser, Crowd Pleaser

In February at Slate NYC, more than 150 Penn Arts & Sciences alums and friends gathered to socialize—and to learn about the science behind such connections. The event, the latest in the Ben Talks series, was hosted by Dhan Pai, W’83, PAR’12, PAR’15, of the Penn Arts & Sciences Board of Advisors, and Heena Pai, PAR’12, PAR’15, with the host committee.

The evening began with dinner, followed by five short talks on topics from the evolution of cooperative behavior to how we navigate our world. After the presentations, Joseph Kable, Professor of Psychology and director of the Mind Center for Outreach, Research, and Education, led a discussion and Q&A.

“The professors were so interesting, so eloquent,” says Manisha Manglani, C’01. “The topic was relevant for so many of us trying to navigate coming back to work full time, socializing with friends after years.”

Part of the discussion centered on the physical effects of being antisocial, which struck Ryan Weber, ENG’04, W’04. “To make sure you have those strong social connections is super important for not just your mental health, but your physical health as well.”

Slate NYC offers foosball and giant Jenga, pool and ping pong, along with plenty of places to relax and catch up. It made for a great backdrop to the evening, says Pravin Manglani, ENG’01, W’01. “We’re here in New York City in a very social setting with games and food and drinks, getting together to learn a little bit about the theory about being social.”

Coren Apicella: Making Cooperation Go Viral

Associate Professor of Psychology Coren Apicella drew lessons about cooperation by experiencing Pandemic—the best-selling board game. By its design, the game requires players to work together to save humanity, “revealing our vulnerabilities when we fail to cooperate,” she says, “but also showing us what we can achieve when we do cooperate. … We saw it in the real-life pandemic, too.”

According to Apicella, human cooperation is distinct from other animals. “In humans,” she says, “cooperation extends beyond our relatives. It extends beyond our friends to include strangers. And our cooperation can scale up from small groups to millions of people.”

Apicella’s work focuses on how biology and culture influence our social choices, including who we pick as a mate, what kind of economic decisions we make, and whether we cooperate or compete with one another. Her conclusions are drawn from work in a laboratory environment, as well as through fieldwork studying the Hadza, a hunter-gatherer population in northern Tanzania.

Apicella says that the Hadza provide a window into the evolutionary origins of cooperation, and her observations of them suggest that this facet of human behavior may be better understood as the product of a social dynamic rather than as a stable personality trait.

The Hadza live in small, nomadic groups. As they move around and encounter others, new groups form and old ones disband. Apicella observed that an individual’s inclination to cooperate would change along with changes in the group—reflecting the group’s cultural norms. “Humans are an ultra-cultural species,” she explains. “We have adaptations for acquiring our beliefs, our values, our behaviors, our practices, our rituals—all sorts of things from the people around us. Culture is what determines who we cooperate with, how we cooperate, and to what extent we cooperate.”

To Apicella, these findings are good news. What this suggests, she argues, is “that we don’t have set limits on our levels of cooperation, that cooperation isn’t fixed, and that each of us can play a part in making the world a more cooperative place. Just by cooperating with the people around us, we can get cooperation to spread.”

Erol Akçay: The Social Inheritance of Connections

Typically, we understand evolution and natural selection in terms of a genetic inheritance passed on from parent to offspring. But “genes are not the only thing that are passed on,” notes Associate Professor of Biology Erol Akçay. “A lot of organisms like plants or animals pass on symbionts [organisms living in symbiosis with that individual] or microbiomes to their offspring.”

Akçay explores the evolution of complex social and biological organization, in contexts from plant-microbe mutualism to animal and human behavior. As a theoretical biologist, his work applies mathematical modeling, simulation, and analysis of existing data to explore a range of topics. His group considers such broad questions as how natural selection shapes the structure of social interactions, and why humans and other highly social animals cooperate, even when doing so offers no direct benefit.

In humans, Akçay says, the non-genetic legacy includes cultural inheritance, “things that you hear from your parents, things that you hear from elders, things you hear from your peers, and that will determine your behavior.” And recent work by Akçay’s group has explored how social connections become a part of the non-genetic inheritance.

Akçay’s group started with 27 years’ worth of detailed data about hyenas that had been collected by zoologist Kay Holekamp of Michigan State University. Hyenas are highly social animals that live in groups as large as 100 or more members; their society is hierarchical, where females are dominant. Holekamp’s fieldwork provided a wealth of information about the structure of the hyenas’ social networks. But Akçay wondered, what was the process through which these structures became established?

By combining Holekamp’s detailed individual-level data with a mathematical model Akçay and colleagues developed, they were able to document a close correlation between the social networks of a mother and her offspring. Furthermore, they were able to show that a hyena’s social network inheritance correlated with the mother’s rank: the higher her rank, the more closely her offspring’s social network would align with her own.

“This sort of social inheritance process—this social inheritance of connections—can actually explain a lot of the patterns that we see in animal social networks in nature,” Akçay says. “In fact, it also correlates with their survival.” Whether it’s the rhesus macaques of Cayo Santiago, humans, or any other social species, the data draw a straight line between wellness and strong social connections.

Joseph Kable: Giving Connections a Second Chance

Joseph Kable’s research focuses on how we make decisions, including the underlying neural mechanisms of choice. A professor of psychology, Kable is also director of MindCORE. In recent work, he and colleagues have explored the processes that drive the decisions we make about other people, and in doing so, the researchers have shed some light on how sociality may change over the lifespan.

To evaluate how people make decisions about social connections, Kable’s team designed a study in which one group of subjects was given $10 and then had the option to either keep it or split it evenly with a subject from a second group. The first group of subjects would be photographed so that the second group could identify who was “fair”—those who split the $10 with them—and those who were not. The second group was then given a choice about whether to have an additional interaction with a person who they knew to be “unfair” or with a random individual. The selection subjects made, it turned out, correlated strongly with their age.

Study participants ranged in age from 18 to 80, and Kable says they found “really profound differences” in social decision-making across age groups. “In the 18- to 21-year-olds,” he says, “they really remember the people who didn’t give them the $5, and really avoid them the next time they have a chance.” Subjects on the older end of the continuum were more likely to try another round with someone who was “unfair.”

As Kable sees it, the apparently more forgiving approach of the older participants may reflect a higher valuation of sociality. He explains, “Even if they think, ‘That person was unfair to me before,’ there seems to be a bias to say, ‘But I’m going to give them another shot. I’ll interact with that person rather than another random individual.’ What we’re seeing is that as people get older, they seem to recognize this wisdom of social connections, and try to give people, and those connections, a second chance.”