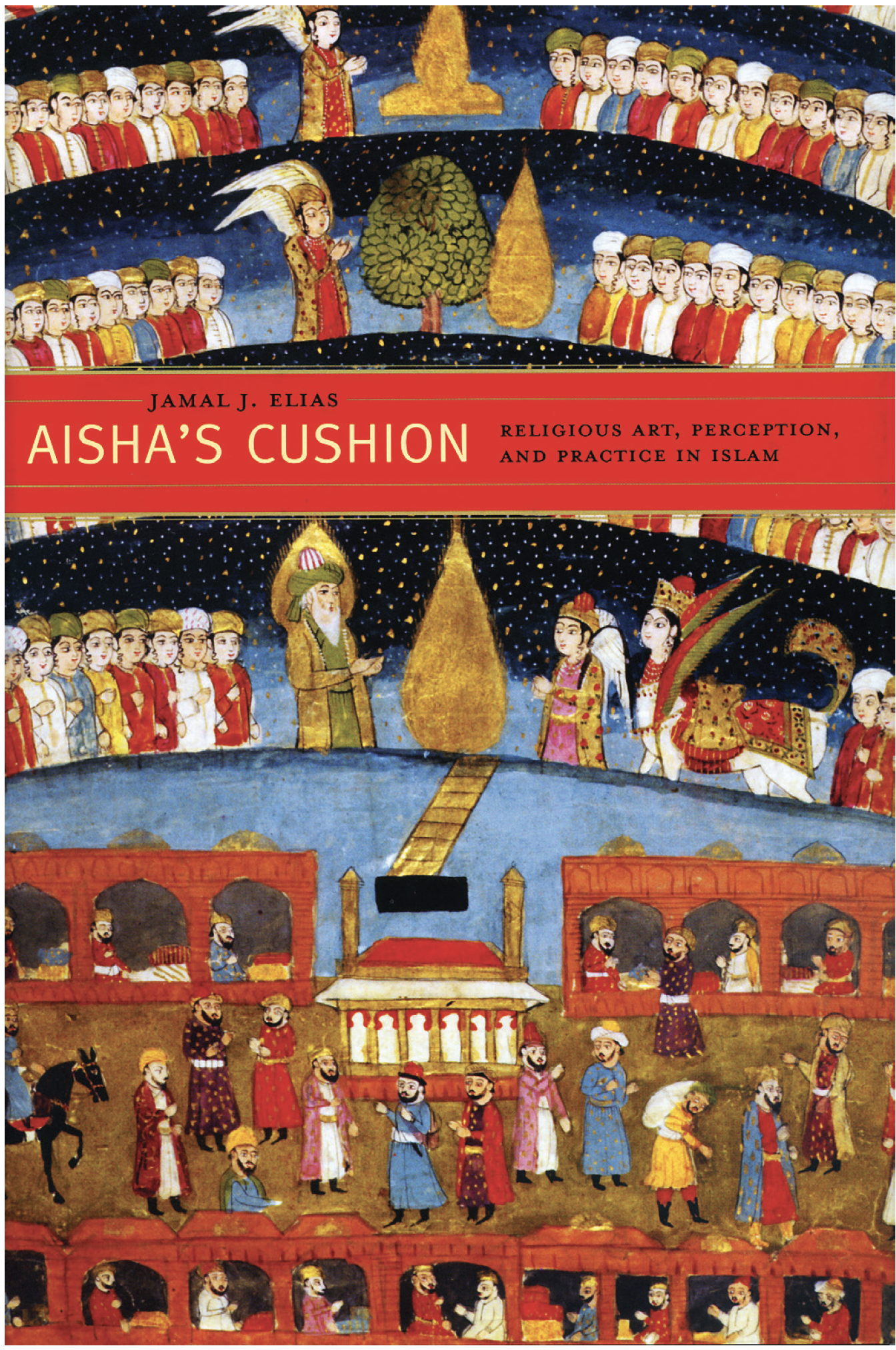

Though many of history’s most recognizable pieces of art are religious in nature, scriptures and secondary texts from these same religions sometimes condemn the veneration of visual images. The reconciliation of the two is part of a complex narrative deriving from societal norms, says Jamal J. Elias, Walter H. Annenberg Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Religious Studies and South Asia Studies. In his book Aisha’s Cushion: Religious Art, Perception, and Practice in Islam, Elias deconstructs prevailing narratives that seek to define Islam’s relationship with art in easy terms.

“The Danish cartoon scandal is a good example of how the argument that Islam is anti-art gets framed in false terms,” says Elias. “The controversy was never about the images themselves—most of the protestors didn’t even see the cartoons in question—but rather about the perceived intentions of all parties. It evolved into a culture war between certain Muslims and Europeans that played out on the international stage. The Muslims accused Europeans of moral hypocrisy and the Europeans turned around and accused Muslims of being backward and intolerant. Art is entirely out of the picture at this point.”

The fallout of such conflicts often affects a culture’s own relationship with its artifacts. Elias cites the current Saudi project to modernize Mecca—the physical heart of the Islamic world—as a prime example. As part of the modernization, many shrines and other edifices venerated by Muslims are being intentionally destroyed, an act in keeping with the dominant Saudi religious ideology which considers veneration of relics and objects to be anathema. Other components of the modernization protest what some Muslims consider Britain’s claim of global centrality. “The Saudis erected a copy of the Big Ben clock tower, and put it on ‘Mecca time’ rather than Greenwich Time. It’s an iconoclastic act, without actually harming Big Ben.”

The notion that Islamic culture seeks to stifle art couldn’t be further from the truth, Elias says. Islam has rich traditions of book, musical, architectural, and metallurgical arts. Misinformed claims like this are due in part to modern society’s tendency to label what is and isn’t art. “When a sword-maker used to make a beautiful sword, he was an artist in his context. But today a sword-maker is not an artist unless the sword is installed in an art gallery. In contemporary society, art is defined primarily by intentionality, but historically, artistry was everywhere.”

While it is taboo to display portraits of Muhammad in most Muslim societies, it is not necessarily forbidden—a claim often erroneously perpetuated by international news coverage. Iran, for example, has a longstanding tradition of religious portraiture. Muslims don’t normally base their reactions to religious images on rules or doctrine, but on the intentions behind the art, Elias says. “Muhammad is depicted in a frieze on the Supreme Court building of the United States. No one gets worked up about it because the intentionality is positive. The real issue has never been the art—it’s the narratives surrounding it.”