Reflecting on a Father’s Wartime Experience

In this excerpt from his book “Fighting the Night,” Paul Hendrickson recounts the time his Nonna tried to prevent her son-in-law—Hendrickson’s dad—from being sent overseas, one of many tales about his father’s time during World War II.

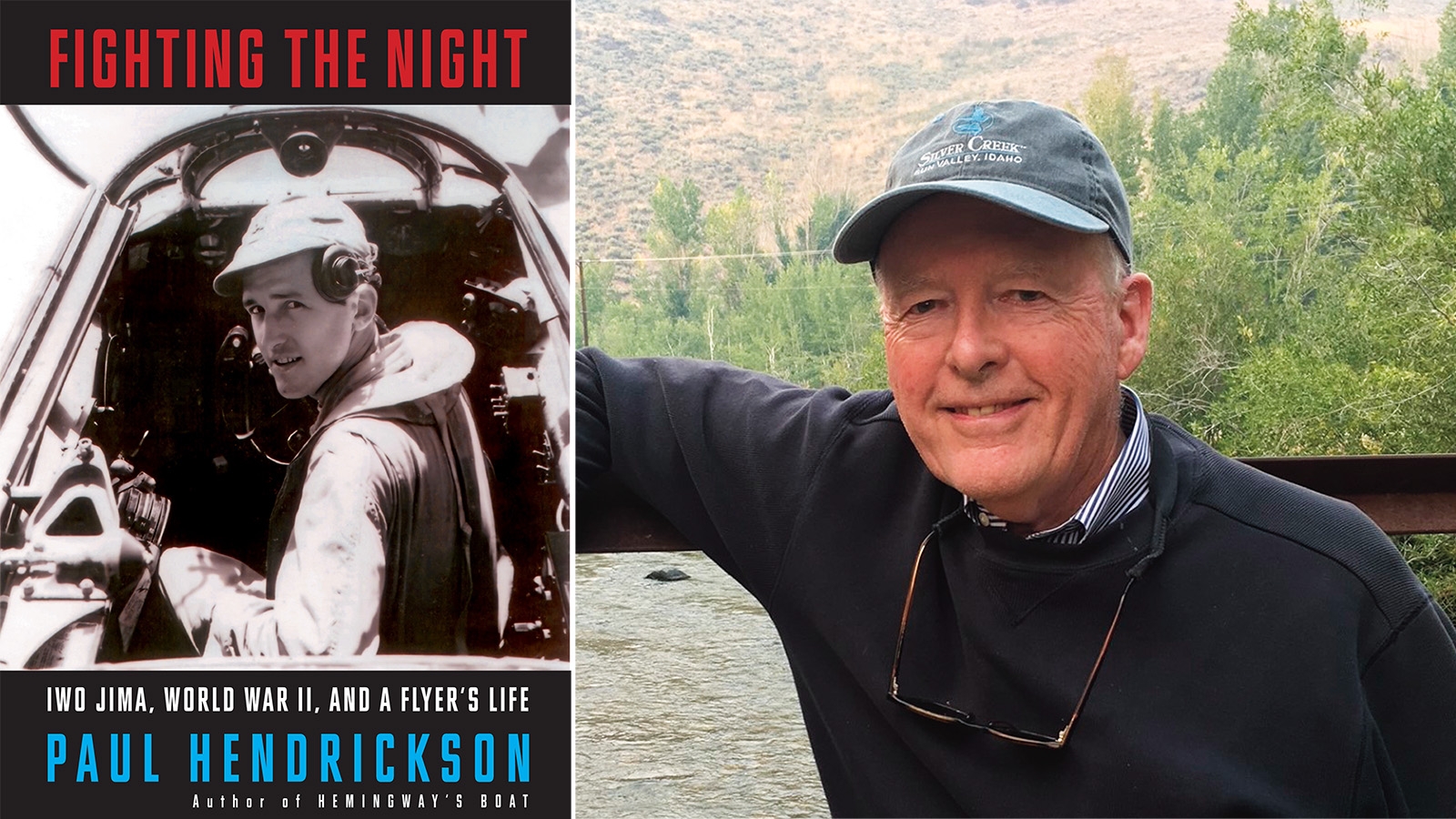

In Paul Hendrickson’s latest book, Fighting the Night: Iwo Jima, World War II, and a Flyer’s Life, Henrickson recounts the history of his father, Joe Paul Hendrickson, as he enlists, gets married, travels across the country from base to base with his new wife, and eventually gets called up to service in 1944, a 25-year-old First Lieutenant leaving at home his 21-year-old wife and two young children.

The excerpt here reveals the complicated notions of family and honor, obligation and allegiance as Hendrickson’s grandmother, whom they all called Nonna, writes to then-First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in an attempt to prevent her son-in-law from being sent overseas.

When I was growing up, it was just another good Nonna story, among so many Nonna stories: the time my maternal grandmother wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt, trying to keep my dad from being sent overseas to the war. She wanted the president’s wife to intervene in some way so that my father would be ordered to stay stateside and take care of his newly pregnant wife. “Wanted” would be putting it mildly. This was June 1942. My father had been in the service for four-and-a-half years then. My dad had been Nonna’s son-in-law for four months. If it was a good story later, it wasn’t so funny at the time. I’m not exactly clear on when my father found out, but when he did, I don’t think he spoke to her for a while. He felt Nonna’s interference was going to hold back his career. Apparently it didn’t hold back a thing. Indeed, I’m wondering if Nonna’s famous letter, famous in our family, didn’t do my dad sly good with some military superiors who had unstoppable mothers-in-law of their own.

I picture Nonna writing her letter to the First Lady—in blue fountain-pen ink on two sheets of plain, white, 8.5x10 stationery, the kind you might buy at Woolworth’s—late at night, in one take, at an oilcloth-covered table in her Ohio farm kitchen. Her husband, my Pop, unaware, has gone off to bed. Even if he’d been awake and aware, I doubt Pop might have tried to halt Nonna. Once she set her mind to something, the more so if it had anything to do with perceived harm to family, Nonna was her own force of nature.

Her first name was Isadora, shortened to Dora. She was first-generation Irish, deeply religious, descended from Conleys and Murphys. She was reed thin. She was a ’50s health cultist, with all sorts of wild-seeming theories, which turned out to be not so kooky, after all, in the years after she was gone.

Nonna told me once, in reference to my brother Marty, who was often in trouble as an adult of one minor kind or another, that she would mortgage her house and anything else she possessed, if it came down to saving him from jail (which he was threatened with a time or two in his life). It wouldn’t have mattered to her that she might be enabling his bad gambling habits or bailing him out of other kinds of debts, some of which weren’t minor. “He’s my flesh and blood, Paul,” she said. That was that.

In her Eleanor letter, some of her sentences crowded the margins, and Nonna also employed a string of ampersands and other abbreviations: not a second to waste. She put the date at the top: “June 20, ’42.”

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt,

Please pardon me for taking up your valuable time but I am coming to you for a very grave matter. You being very broad-minded, I know you will do something about this matter about which I am making an appeal.

My daughter (Rita Kyne Hendrickson), the wife of 2nd Lt. Joseph Paul Hendrickson is three months pregnant & of course is expecting a baby the last of November or the first of December. They were married in February and she is 19 years old. I am making sacrifices and all of us are willing to make sacrifices to win the war but as many of the soldiers are being sent overseas we naturally feel like he may get orders sometime to go. Don’t you think he is greatly needed in this country now and it is important that he be with her the next 6 months to come? She will be needing medical care & attention from him & he will be worried & sick if he isn’t with her so I think it would be the death of the three of them. . . .You as the mother of six children can see how important it is that he be left in the States & I know can & will do something about it.

Toward the end: “I am enclosing stamps for your sending of registered mail about this matter—to whom I do not know.” Tagged on: “I will appreciate this Mrs. Roosevelt & always remember you as a friend & thank you. You see I can talk frankly to you on this subject as ‘woman to woman.’”

In her P.S.: “Please give it your immediate attention.”

She signed it, “Mrs. Bernard Kyne, Xenia, Ohio, R.3. Cin. Pike. The “Cin” stood for Cincinnati. Pop and Nonna’s farm sat off the Cincinnati Pike, a few miles south of Xenia. It’s the farm where my mom grew up.

I wonder if FDR’s wife even saw it. It seems clear somebody on her staff saw it (and possibly pocketed the stamps). About two weeks later, a high officer in the Adjutant General’s Office in Washington wrote to Nonna in his best, straight-faced, governmental voice. (I can see Nonna’s letter getting passed around the office: Hey, Guys, check this one.)

“Dear Madam,” began Major General J.A. Ulio.

Reference is made to your letter of June 20, 1942, addressed to Mrs. Roosevelt, in the interest of your son-in-law, Second Lieutenant Joseph P. Hendrickson, in which you requested that he be assigned to some unit which will not leave the United States.

Your anxiety in this matter is appreciated, however, this office regrets very much that no assurance can be given at this time of Lieutenant Hendrickson’s continued duties within the United States.

The adjutant’s reply was dated July 3, 1942. That same day, my mom and dad, innocent of it all, were aboard the Super Chief, out of Chicago, headed back to San Bernardino, where they’d been posted several months before, and where my dad would now await orders in the fall for flight school. The day before, on the 2nd, they had left Xenia by rail, had changed in Dayton for Chicago, had arrived in the Windy City on the morning of the next day, had spent that day seeing a few sights, and at suppertime had boarded for the Coast.

I’m wondering if Nonna’s famous letter, famous in our family, didn’t do my dad sly good with some military superiors who had unstoppable mothers-in-law of their own.

A week earlier, my dad had graduated from eight weeks of temporary duty propeller school at Pratt & Whitney’s headquarters in East Hartford. My mom had left Connecticut ahead of my dad and had taken the train to Ohio, via Penn Station in New York, and my dad had then followed her to spend five or six days at the farm with her and his in-laws. Probably he had helped out Pop with some of the chores. He and Pop always got along beautifully.

July 3, 1942, was a Friday. The next day, the national holiday, and the day and night following, this much-in-love couple, just kids, with my older brother Marty starting to grow inside my mom’s stomach, were rolling through Dodge City and Albuquerque and Gallup and Winslow and Seligman and Needles and Barstow, and then right on into San Berdoo in the early hours of the third day out. Sounds pretty sweet: getting to spend the 4th of July, even or especially with a war on, on the crack train of the Santa Fe Railway, looking at their country from the other side of their Pullman glass.

Somehow, I had forgotten all about Nonna’s letter. And then, several years ago, I opened my dad’s thick (and saved) military file at the national archives in St. Louis, and there it was, first document in the folder, staring up at me, its original, hilarious self, not even yellowed or curled. Nonna died in 1978, but suddenly I had her back. I hooted, drawing looks from the other researchers in the reading room.

The above excerpt comes from Fighting the Night: Iwo Jima, World War II, and a Flyer’s Life by Paul Hendrickson. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright ©2024 by Paul Hendrickson.