Política, Activismo, y Academia

The career of Tulia Falleti, Class of 1965 Endowed Term Professor of Political Science, grew from her activism as a student in a newly democratic Argentina.

When she was in the sixth grade, Tulia Falleti’s father took her to a marble building that spanned a whole city block. They entered through columns and arches and visited the multi-floor library with dark wood walls lined floor-to-ceiling with books and topped by ornate, domed skylights. It was the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires, and she was enchanted.

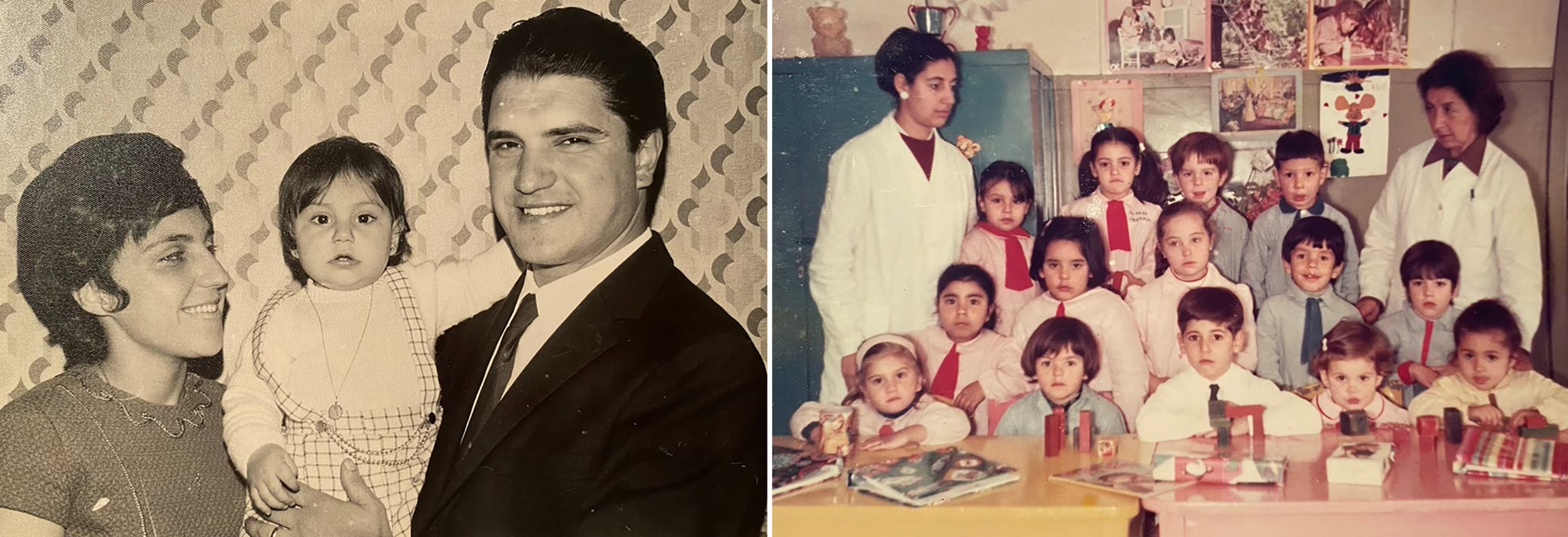

The trip was part of Falleti’s parents’ plan to make education an integral part of their children’s lives, though they did not receive it themselves. She and her two siblings grew up in what she describes as a lower-middle-class neighborhood in Buenos Aires at a time when Argentina was transitioning out of a violent dictatorship and into a democracy, a transition that would ultimately shape her career. Her father, Brunello Falleti, had begun an engineering program but ultimately left because he did not have a strong foundation in math, while her mother, Rosa Bracaccini, who Falleti calls “an amazing student,” had to leave school at only 13 years old to care for her own mother, who had been paralyzed.

“They always instilled in my siblings and me the idea that we were going to go to college,” Falleti, now Class of 1965 Endowed Term Professor of Political Science and Director of the Center for Latin American and Latinx studies, remembers. “It wasn’t a question. It wasn’t something debatable—we were going to college.”

Falleti, also Senior Fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, is now a noted political scientist. She published her first book, Dominación política, redes familiares y clientelismo, with Fabián E. Sislian in 1997 while still a student, and she was an assistant professor at Penn by 2004. Her first solo book, Decentralization and Subnational Politics in Latin America, came out in 2010 and was named the best book on political institutions by the Latin American Studies Association.

Her current research focuses on Indigenous politics— a subject she says is under-studied across political science. She previously published on how citizen participation can affect public services at the local level, along with Emmerich Davies, former graduate student and current Harvard Graduate School of Education faculty member, and Santiago Cunial, a doctoral candidate in political science. This work led her to study when and how Indigenous communities in South America are consulted about infrastructure projects that impact their land.

Falleti began studying Indigenous political organization in Bolivia alongside Thea Riofrancos, then a political science graduate student and now a faculty member at Providence College. From there, she researched the rights and demands of the Mapuche people in the southern regions of present-day Argentina and Chile, and the Wichí in the north of Argentina.

All of this was on her mind in the summer of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic continued and protests against police violence swept the United States, and then the world. “I was already trying to address questions of why my discipline had been making invisible Indigenous peoples and their organization, their demands,” Falleti remembers. “In political science, we’ve been studying states as if they are units that are more or less homogeneous, even when we recognize that they may be multicultural—we refer to them as nation states with the implication that there is one dominant nation.”

Falleti’s desire to shine a spotlight on what had previously been made invisible motivated her to envision a research project enormous in its scope: from South America to Canada, from 1492 to the present. In 2021, her bold vision was recognized with a $5 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and her interdisciplinary project is now underway.

Community Commitment

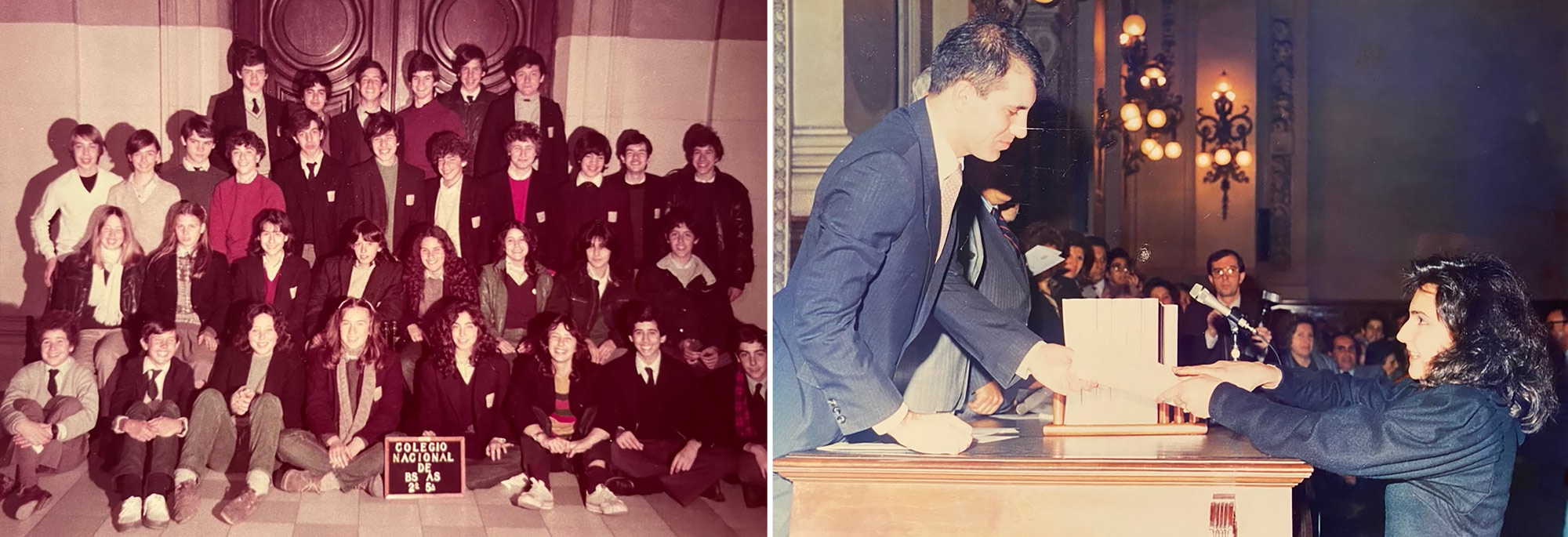

Falleti’s journey to college began on that trip to the Colegio Nacional, when she fell in love with the beautiful building and took an entrance exam that allowed her admittance to the public, but highly selective, high school. Because the school was run by the University of Buenos Aires, students who attended did not have to take additional college exams. Another benefit of the school’s university affiliation was an innovative curriculum and a pride in its long history and prestigious alumni—Nobel prize winners, former presidents, and top scientists had all attended. Along with that pride came a sense of responsibility and commitment to social justice.

As I entered the first year of high school in 1983, Argentina started a transition to democracy from a military dictatorship. We were in this elite and leading public school at a time of political opening and our student union was extremely active in supporting social causes and demonstrations for democracy.

Falleti explains, “As I entered the first year of high school in 1983, Argentina started a transition to democracy from a military dictatorship. We were in this elite and leading public school at a time of political opening and our student union was extremely active in supporting social causes and demonstrations for democracy. We were transitioning to a new political regime, one that was much more open, but where there was a sense that a lot of justice had to be done.”

One of the biggest injustices that needed to be addressed was the plight of the desaparecidos, or, the disappeared. In the 1970s, the military junta that overthrew Isabel Perón as President of Argentina began kidnapping, torturing, and killing people associated with leftist or social justice causes. An estimated 30,000 people were disappeared, and their families’ search for justice continues today.

Even under a democratic regime, the specter of the disappeared hung over Falleti’s activism. As she and her classmates raised awareness, protested against the International Monetary Fund, and tutored disadvantaged students in the area, her family worried about what would happen in the event of another dictatorship.

“Since the 1930s, the history of Argentina had been a succession of military dictatorships followed by weak democratic governments, and then there was another coup and another military dictatorship,” Falleti says. “Because of my activism, my parents were very afraid that if there would be another military dictatorship, we could be disappeared. But of course, you’re a teenager and you do what your parents don’t want you to do.”

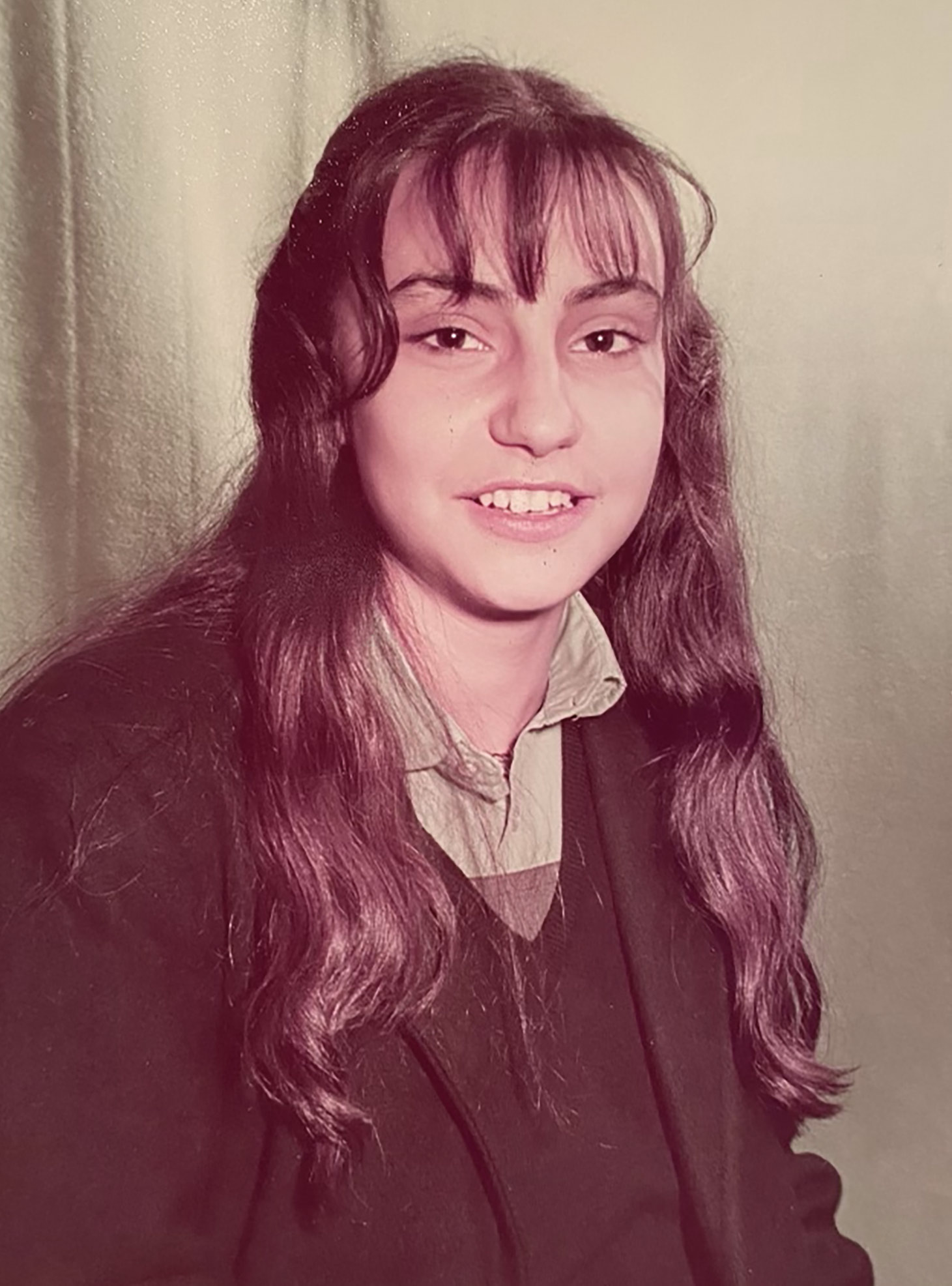

A combination of her teenage rebellion, social commitment, and love of learning motivated Falleti to decide to study sociology at the University of Buenos Aires. There, she learned the building blocks that prepared her to switch fields into political science.

Reflecting on her college days, she says, “I loved biology and at one point I thought I wanted to be a doctor. But in the end, I decided that I would do sociology. It was related to my political activism. I went into sociology just because I was fascinated by what I would be studying, not because I had any idea of what I would do afterwards with my degree.”

By the early 90s, Falleti was teaching at two universities in Buenos Aires and struggling to make ends meet. She’d been studying English since high school and had always been fascinated by American higher education.

“So,” she says, “In 1995, I applied to doctoral programs in the U.S. But of course, you’re in Argentina, there is no internet. I would request brochures and all of my applications were mailed.”

When considering where to apply, she realized that many sociology departments in the U.S. seemed to be focused on topics related to the U.S. But she came across something called comparative politics in political science departments, where people studied political regimes. On discovering the field, she remembers thinking, “It was all I wanted to do.”

She ended up at Northwestern University in Chicago, a city that she had never visited. She chose it largely because of Edward Gibson, a scholar with an Argentine father who had spent part of his childhood in the country. Gibson, until recently a vice dean at Northwestern, studies Latin American politics. At Northwestern, Falleti felt she would have the opportunity to learn about the things she cared about—political regimes, the relationship between states and societies—within the traditions of a new discipline.

“And that’s how I chose political science over sociology,” she recounts. “Then, the rest is history!”

A Distinguished Career/ Una Carrera Distinguida

Falleti finished her Ph.D. at Northwestern in 2003 and was off to a running start.

Early in her career, Falleti prioritized the most prominent, highly regarded journals and publishers in her field. This meant mostly publishing in English and, she admits, a certain naiveté.

“I remember when I was a post-doc at the University of British Columbia, I mailed my article-length manuscript based on the main argument of my dissertation to the American Political Science Review, the flagship journal of my discipline,” she says. “It was like, ‘Oh my gosh, there goes that FedEx envelope with my little baby inside.’ I remember thinking if they rejected it, I would die.”

The journal asked for a revise and resubmit— a response from an academic publisher that requests changes but offers the hope of publication. The journal published her article, “A Sequential Theory of Decentralization: Latin American Cases in Comparative Perspective,” in 2005, and the following year, it was given the Gregory Luebbert Article Award for best article in comparative politics from the American Political Science Association. In 2006, Falleti published a Spanish translation of the article in Desarrollo Económico.

“I was so naïve, sending it to the best journal in the field, with an over 90 percent rejection rate,” Falleti says of her younger self. “I got the R&R. I guess I got lucky. I was committed to doing the things I needed to for my career.”

Falleti has continued publishing since: in collaboration and solo, and in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. She’s known for her expertise in comparative politics, the field that caught her attention as she pondered graduate school, and Indigenous politics, Federalism, and health care systems, among other topics.

The sense of community that was first instilled in her as a student at the Colegio Nacional has influenced her career.

I’m a product of the public education system in Argentina. I know that many students there are not proficient in English. I feel like I have a certain responsibility to give back.

“I’m going every year back to Argentina, and sometimes other countries like Bolivia, Brazil, or Chile. I have a network there of peers,” she says. “And, I’m a product of the public education system in Argentina. I know that many students there are not proficient in English. I feel like I have a certain responsibility to give back.”

Spanish and Portuguese publications—like that first award-winning article—are the result of that feeling. Falleti often retains the rights to translate her own work, so that if she is particularly proud of a piece, she can publish it in a Spanish-language journal, or if an article is about Brazil, she can make it available to speakers of Portuguese.

Dispossessions in the Americas

Falleti’s network in South America and at Penn was on full display in her proposal for the interdisciplinary project recently funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The project, called Dispossessions in the Americas: The Extraction of Bodies, Land, and Heritage from La Conquista to the Present, has two aims. First, to document territorial, embodied, and cultural heritage dispossessions in the Americas, and second, to outline how the restoration of land, embodiments, and cultural values can recover histories and promote restorative justice. It will partner with over 40 institutions and community groups across the Americas and counts among its collaborators faculty, curators, undergraduate and graduate students, and postdoctoral fellows from across Penn and the Americas.

In the aftermath of so much suffering and loss, it’s important to be able to document the ways in which the effects of this pandemic and other crises are mounted on structural, systemic inequalities and dispossessions that you can trace back 500 years.

Falleti coordinated the project in response to Mellon’s Just Futures initiative, which called for proposals from multidisciplinary, university-based teams committed to racial justice and social equality. She recalls reading the call for proposals in summer 2020: “It’s hard to believe that this initiative was not a direct response to everything that was happening in the U.S. during that summer, and the fact that the killing of George Floyd and the pandemic revealed entrenched issues of systemic racism and inequalities like never before. In the aftermath of so much suffering and loss, it’s important to be able to document the ways in which the effects of this pandemic and other crises are mounted on structural, systemic inequalities and dispossessions that you can trace back 500 years.”

Reading about Just Futures allowed Falleti to imagine a large-scale project that could bring oft-neglected stories and communities into the spotlight. But not without a large team and considerable community participation.

Falleti started assembling her team by calling on colleagues in the Department of Africana Studies. Next up, the Native American and Indigenous Studies Program. Before long, she was working with faculty affiliated with the Departments of Anthropology, History, and History of Art, and the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program, Penn Cultural Heritage Center of the Penn Museum, and the Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Informatics in the Perelman School of Medicine.

The proposal was accepted and received a $5 million grant. The funds will allow Falleti and collaborators to create a multilingual website; host conferences; publish journal articles, an art catalog, and two coedited volumes; develop arts and performance events, and participate in the design of cultural heritage museums in Mexico and Belize.

Falleti says, “It’s very important to put forward proposals that could give hope. It’s not only documenting what was lost, but also proposing measures for restorative justice, for healing, that are built from the ground up with communities.”

What exactly restorative justice means, she says, will be defined by the Indigenous and Afro-descended communities the project partners with. What she is certain of is that working toward justice can shape a different future.

“It’s not so much what I think should happen,” Falleti says. “It’s more important what the communities and the legal experts working with these communities imagine as aspirational policies. Perhaps they are not all possible now, but let’s establish an agenda for the future. Some of the Indigenous rights that are rooted in the U.N. Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples are aspirational and not all are implemented in the countries that have ratified the declaration. But this future horizon is very important, and that’s the part of the horizon that we want to contribute to building together.”

A Home at Penn

People often say that dreaming in a new language is a signal of true fluency. Falleti passed that milestone years ago. But English will never be her first language, and speaking Spanish will always conjure a sense of home.

“As an immigrant from Latin America, many times you find yourself at odds with the majority of the population—at odds in the sense that your culture, your history, your language are different,” Falleti says. “You’re most relaxed when you speak your own language, right? You get to the most precise reflection of your thoughts when you’re speaking in your first language.”

The feeling of being at odds is why Falleti’s position as director of the Center for Latin American and Latinx Studies is so important to her. Thinking about why she took on the role, she says, “It was more than just directing an undergraduate curriculum program. It was building a community, or coming together with a community, where I felt in many ways closer to home.”

The center’s history dates back to 1988, when Nancy Farriss, Professor Emerita of History, founded the Latin American Cultures Program, which focused on faculty expertise in the anthropology, archaeology, and ethnohistory of Latin America. The program evolved to include the study of the fluidity and hybridity of transnational cultural and identity construction and the experiences of Latinx people in the United States. After Farriss, Ann Farnsworth-Alvear, Associate Professor of History, and Emilio Parrado, Dorothy Swaine Thomas Professor of Sociology and a fellow University of Buenos Aires graduate, took the helm. Falleti became the director five years ago, and, in the spring of 2021, the program officially became a center.

Through it all, students have always been at the heart of the community, from courses for majors and minors to guest speakers that address pressing issues. Students are leaders in the Penn Model Organization of American States program, a university–community-based program engaging undergraduate and high school students in academic, experiential learning to explore solutions to the most pressing problems facing the Americas.

Students also led the drive for a recent change, Falleti says. “About two years ago, we included Latinx in the program’s name,” she explains. “This was a student-led change; the trans community among our students didn’t feel represented by the “Latino” terminology. We had an academic panel where we discussed the differences between Latino and Latinx and what it meant to people in academia and also to people who are activists or in local politics. Students gave us the push to do this work, and everyone was on board.”

When the program became a center, Falleti called it “the realization of a dream.” The new designation opens up exciting new possibilities, particularly around research. In addition to having more funds to support student and faculty research, the center will host postdoctoral fellows, visiting scholars, and public lectures.

Key to the center’s success is its interdisciplinarity. “The problems we have in Latin America and with Latinx communities are very complex,” she explains. “Our competitive advantage is that we have this amazing interdisciplinary community. Let’s bring problems to the table so that we can tackle them from different disciplines, with grad students and undergrads coming from different departments.”

In the spirit of interdisciplinary research, the center has launched two research clusters. One, focused on Afro-Latin Americans and Afro Latinx epistemologies, is led by Farnsworth-Alvear and Odette Casamayor-Cisneros, Associate Professor of Romance Languages. The other cluster studies environmental justice and is led by Kristina Lyons, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, and Falleti. Graduate and undergraduate students will also participate in research with both groups.

Ultimately, directing the center combines Falleti’s academic expertise with her lifelong commitment to community.

“It is a point of pride to show the rest of the university what Latin America is about and to highlight what do we do when we write in Spanish or in Portuguese and why it’s important,” she says. “To serve our diverse community has been a pleasure, an honor.”