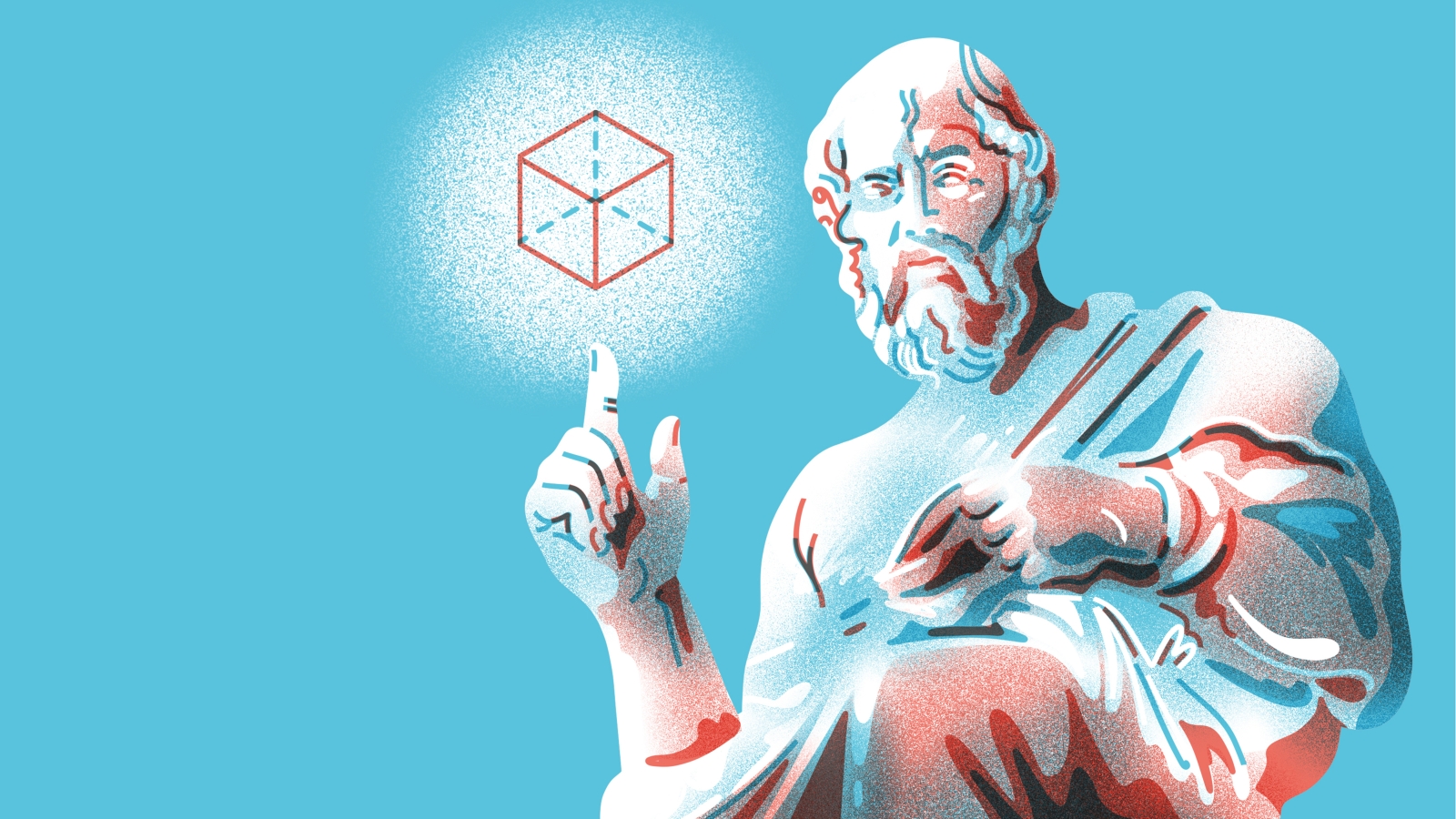

Plato Was Right. Earth Is Made, on Average, of Cubes.

Earth and Environmental Science’s Douglas Jerolmack and colleagues have found that the ancient Greek philosopher was onto something.

Plato, the Greek philosopher who lived in the 5th century B.C.E., believed that the universe was made of five types of matter: earth, air, fire, water, and cosmos. Each was described with a particular geometry, a “platonic shape.” For earth, that shape was the cube.

Science has steadily moved beyond Plato’s conjectures, looking instead to the atom as the building block of the universe. Yet Plato seems to have been onto something, researchers have found.

In a paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Douglas Jerolmack, Professor of Earth and Environmental Science, and colleagues from Budapest University of Technology and Economics and the University of Debrecen in Hungary use math, geology, and physics to demonstrate that the average shape of rocks on Earth is a cube.

The group’s finding began with geometric models developed by mathematician Gábor Domokos of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, whose work predicted that natural rocks would fragment into cubic shapes. Domokos pulled two Hungarian theoretical physicists into the loop: Ferenc Kun, an expert on fragmentation, and János Török, an expert on statistical and computational models. The researchers took their finding to Jerolmack to work together on the geophysical questions; in other words, “How does nature let this happen?”

To test whether their mathematical models held true in nature, the team measured a wide variety of rocks, hundreds that they collected and thousands more from previously collected datasets. No matter whether the rocks had naturally weathered from a large outcropping or been dynamited out by humans, the team found a good fit to the cubic average.

Remarkably, they found that the core mathematical conjecture unites geological processes not only on Earth but around the solar system as well.

“Fragmentation is this ubiquitous process that is grinding down planetary materials,” Jerolmack says. “The solar system is littered with ice and rocks that are ceaselessly smashing apart. This work gives us a signature of that process that we’ve never seen before.”

Part of this understanding is that the components that break out of a formerly solid object must fit together without any gaps, like a dropped dish on the verge of breaking. As it turns out, the only one of the so-called platonic forms—polyhedra with sides of equal length—that fit together without gaps are cubes.

Identifying these patterns in rock may help in predicting phenomenon such as rock fall hazards or the likelihood and location of fluid flows, such as oil or water, in rocks.

Legend has it that the phrase “Let no one ignorant of geometry enter” was engraved at the door to Plato’s Academy. For the researchers, finding what appears to be a fundamental rule of nature emerging from millennia-old insights has been an intense but satisfying experience.

“When you pick up a rock in nature, it’s not a perfect cube, but each one is a kind of statistical shadow of a cube,” adds Jerolmack. “It calls to mind Plato’s allegory of the cave. He posited an idealized form that was essential for understanding the universe, but all we see are distorted shadows of that perfect form.”