Ordinary Lives, Extraordinary Times

A fateful trip to Eastern Europe in 1989 inspired Kristen Ghodsee, Professor and Chair of Russian and East European Studies, to pursue a career studying the impact of the Cold War and its aftermath on the lives of ordinary people.

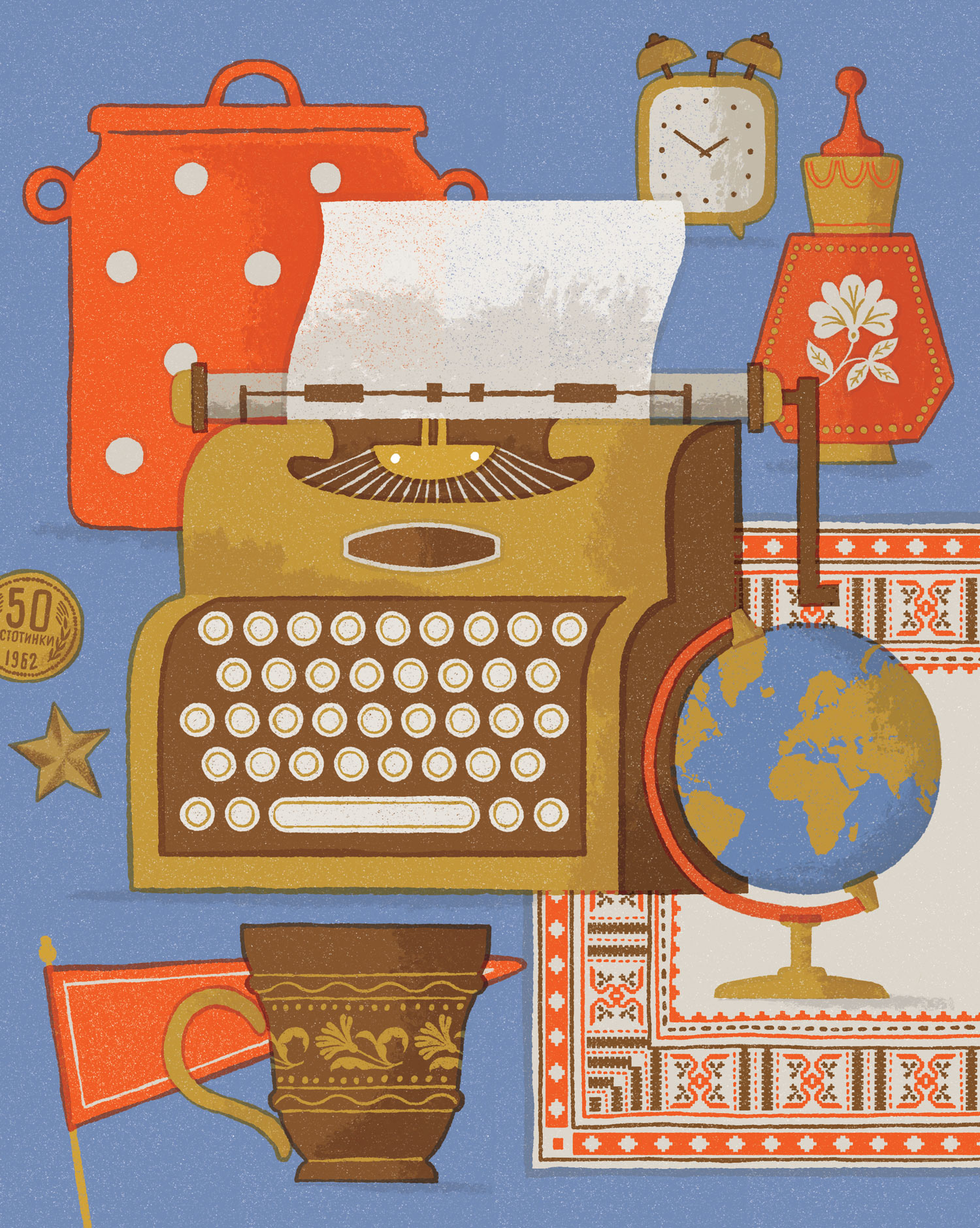

Kristen Ghodsee collects Cold War-era typewriters. Some in her collection are even older, dating back to the 1920s. The majority were manufactured in the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe. Over the summer, while completing a fellowship at the Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies (FRIAS) in Germany, she added three more to her collection.

Kristen Ghodsee, Professor and Chair of Russian and East European Studies

Elena Hmeleva

“Each typewriter tells a unique story,” says Ghodsee, Professor of Russian and East European Studies. In a recent talk titled “Cold War Keys: The Curious Lives of East European Typewriters,” she explained how the machines—once strictly regulated in many parts of the region—shed light on the lived experiences of socialism and post-socialism. A Marista 11 model that she found at a flea market in Sofia, Bulgaria, for instance, invokes bitter memories of the corrupt privatization and liquidation of the country’s once-flourishing typewriter industry.

Ghodsee, who was recently appointed Department Chair of Russian and East European Studies, is a prolific author for both academic and general audiences. She also harnesses other media, like podcasting. Her newest book, Red Valkyries: Feminist Lessons From Five Revolutionary Women, focuses on the lives of five socialist women and their legacy for modern-day feminists, including one from Ukraine—a region which Ghodsee has been reflecting upon of late, given current events.

An award-winning ethnographer, Ghodsee is also interested in the stories that people tell—particularly those of ordinary people living in Eastern Europe during the region’s transition from state socialism to capitalism in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Ghodsee joined Penn in 2017. She was previously a professor at Bowdoin College, where she directed the gender, sexuality, and women’s studies program. Throughout her career, she has sought to understand from Eastern Europeans themselves how the end of the Cold War changed their lives. Much of her research involves fieldwork, specifically in the Balkans and the former German Democratic Republic, where she has lived for months at a time, meeting with locals and learning about the countries’ social, cultural, and political histories. For her first book, The Red Riviera: Gender, Tourism and Postsocialism on the Black Sea, an ethnography of women working in Bulgaria’s popular sea and ski resorts, Ghodsee spent 18 months living in Bulgaria, conducting survey research, and interviewing the women she met, including a waitress, a tour operator, and a travel agent. The book was published in 2005. Ghodsee began this fieldwork as a doctoral candidate in social and cultural studies at UC Berkeley, but the origins of her interest in Eastern Europe date further back—to the summer of 1989.

A Fateful Trip

That year, Ghodsee, who’d just completed her freshman year at UC Santa Cruz, decided to drop out of college. Convinced that the Cold War would eventually escalate to a point that would make any travel impossible, she bought a one-way ticket to Spain.

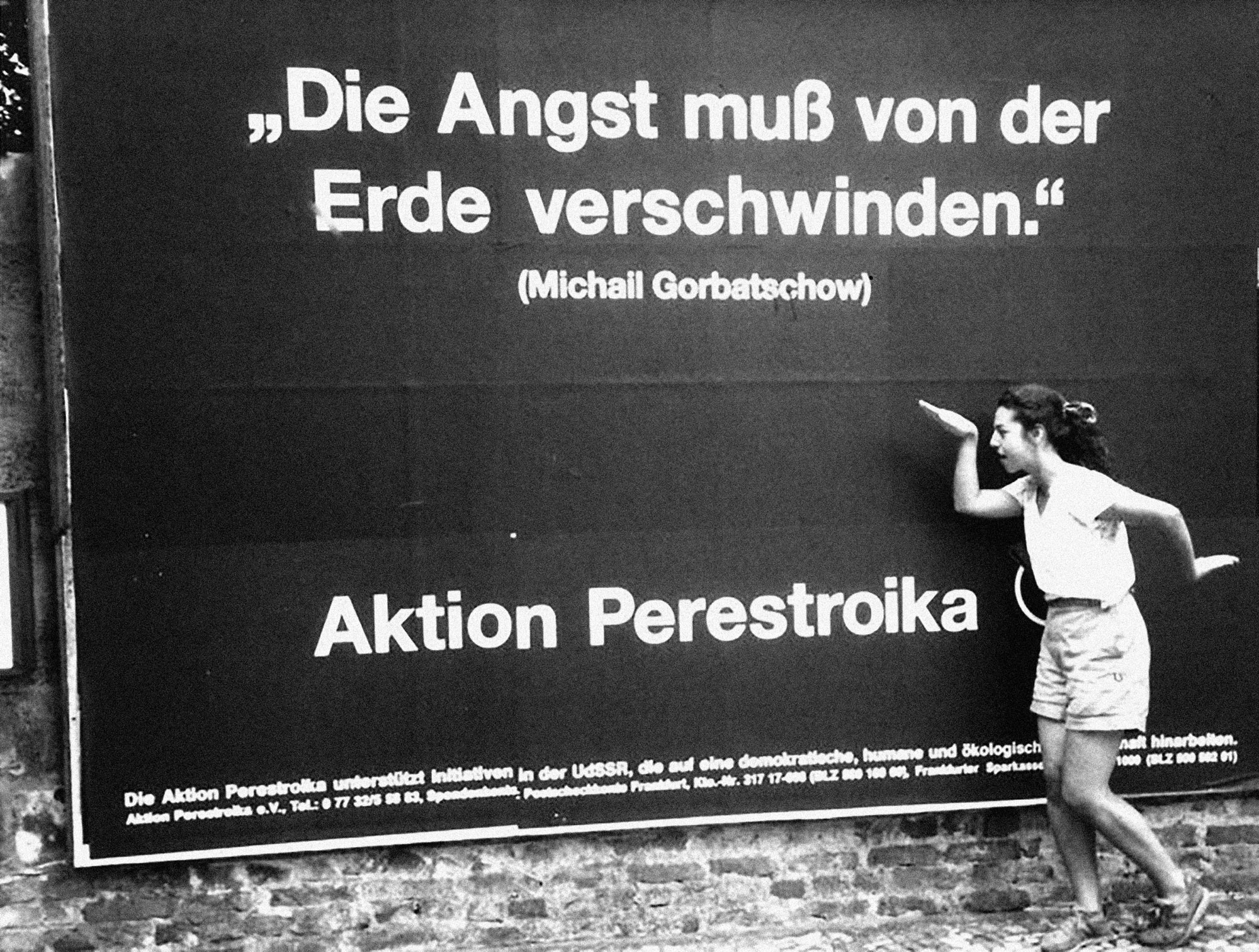

But on November 9, only a few months after she’d arrived in Europe, the Berlin Wall came down, marking the end of the decades-long geopolitical conflict. The timing, Ghodsee says, seemed serendipitous. She began making her way to Germany, eager to witness and take part in the hope and exuberance spreading across the region. Setting off from Turkey, Ghodsee traveled through Bulgaria, former Yugoslavia, Romania, Hungary, and former Czechoslovakia, before finding herself on Alexanderplatz, the plaza in East Berlin where nearly a million people had recently gathered to demonstrate for political reforms. Ghodsee was there with thousands of revelers in the summer of 1990 when East and West Germany unified their currencies.

“It was huge—to be there and to feel the possibility of what the world was going to be like,” Ghodsee remembers, describing the experience as a turning point in her life.

Though she didn’t yet know it at the time, the trip would also go on to shape her career in profound ways. “I did not at all in any way have a traditional path into academia,” Ghodsee says, explaining that, after she returned to UC Santa Cruz the following year, she’d had no clear plans except to pursue opportunities that would allow her to continue engaging with the world. She studied abroad at the University of Legon in Accra, Ghana, during her junior year and spent three years teaching English in Japan after completing her undergraduate studies in creative writing and theater arts. While she’d been interested in political and economic issues since high school, describing herself as “a model United Nations dork,” Ghodsee says that she applied to graduate school on a lark.

A Prolific Career

To date, Ghodsee has held residential research fellowships at several institutions, including FRIAS; the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey; the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University; the Imre Kertész Kolleg at the Friedrich-Schiller-Universität in Jena, Germany; the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, Germany; and the Aleksanteri Institute of the University of Helsinki in Finland. Back in 2012, she won a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship for her work in Anthropology and Cultural Studies, and she was an invited professor at Sciences Po in Paris, France, in 2021.

Ghodsee is the author of 11 books, eight of which are academic explorations of the lives of ordinary people, especially women, in the former Eastern Bloc both under socialism and in the aftermath of the Cold War. Her most recent book, Red Valkyries, which was mentioned in the New York Times Book Review, profiles five socialist women who were prominent activists in the 19th and 20th centuries but whose stories are lesser-known than those of their male compatriots. The book reflects another focus of Ghodsee’s work: the forgotten stories of “people who have these incredible moments of meaning and profundity in their lives and actually end up changing the world.”

Lyudmila Pavlichenko, a Ukrainian-born sniper whose 309 confirmed kills in World War II makes her the most successful female sniper in history, is one of these extraordinary figures. “Ukraine has a long history of women in the army,” says Ghodsee, who writes about Pavlichenko’s resistance of traditional women’s roles in Red Valkyries.

The implications of this history are visible today as the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine continues to disrupt the lives of millions of Ukrainians. “Legislation adopted in 2018 gave Ukrainian women the same legal status as men in the armed forces, and today there are over 50,000 women serving in the armed forces,” in both combatant and non-combatant roles, Ghodsee explains. Since the war began on February 24, 2022, many women have remained in or returned to the country to fight against Russian forces. While in residence at FRIAS this summer, Ghodsee met a psychologist from Ukraine who counseled soldiers at the frontlines of the war via Zoom. “She said that many women are more committed fighters than the young men who were draftees and forced to fight. The women who volunteered are well-trained and deeply committed to the defense of their homeland,” Ghodsee recalls.

The Diversity of Human Experiences

While at UC Berkeley, Ghodsee received a Fulbright grant to conduct fieldwork that would shape the focus of her own interest in Eastern Europe.

“I always knew I wanted to go back—it was just a question of which country,” Ghodsee says. Several factors tipped her in the direction of Bulgaria. At the time, few scholars in the field were focusing their studies on Bulgaria, let alone its tourism industry, the subject of Ghodsee’s dissertation and subsequently her first book, Red Riviera. Because of her own mixed heritage—half Puerto Rican and half Persian—she’d initially considered a transatlantic comparison of Bulgaria’s and Cuba’s tourism industries. But the complications of working around U.S. sanctions against Cuba meant that she would’ve had to shift her research method away from ethnography—the immersive approach to studying a culture or society that would eventually become indispensable to her academic pursuits.

“Ethnography was the motivating thing for me,” Ghodsee remembers. In 2016, she published From Notes to Narrative: Writing Ethnographies that Everyone Can Read, a guide to writing accessible ethnographic texts.

Ghodsee’s first exposure to ethnography came in graduate school, where she learned the importance of fieldwork. In order to fully understand and write about a people’s way of life, “You’ve got to live with those people, speak the language, you have to fully immerse yourself in that culture,” Ghodsee explains. At UC Berkeley, with the fall of the Berlin Wall still fresh in her mind, Ghodsee took a class on the anthropology of Eastern Europe with Alexei Yurchak. “That class, combined with the methods classes I had with these two powerhouse female anthropologists, Carol Stack and Jean Lave, really shifted me in that direction,” she says, explaining her motivations to return to the region in 1998.

In order to fully understand and write about a people’s way of life, you’ve got to live with those people, speak the language, you have to fully immerse yourself in that culture.

For Ghodsee, the greatest draw of ethnography is that it “helps us get in touch with the diversity of human experiences in a way that is deeper and more profound.” Ethnography captures and preserves different peoples’ ways of life, Ghodsee explains, fighting against what anthropologist Wade Davis calls “ethnocide,” or the gradual loss of human cultures and societies. Her second book, Muslim Lives in Eastern Europe: Gender, Ethnicity, and the Transformation of Islam in Postsocialist Bulgaria, which came out in 2010, follows the Pomaks, a group of Slavic Muslims in Southern Bulgaria, and explores how the community’s gender relations shifted in the aftermath of the Cold War. The book won numerous awards, including the 2011 William A. Douglass Prize in Europeanist Anthropology and the 2011 Harvard Davis Center Book Prize in Political and Social Studies. Today, Ghodsee is a member of the Graduate Groups in Anthropology, Comparative Literature, and the Lauder Institute for Management and International Studies, and advises a wide variety of Ph.D. students doing work in or on Eastern Europe.

Extraordinary Lessons

In her fieldwork, Ghodsee’s path has often crossed with those whose untold stories turn out to offer extraordinary lessons. In The Left Side of History: World War II and the Unfulfilled Promise of Communism in Eastern Europe, which was published in 2015, she tells the stories of two people whose socialist ideals inspired them to fight against Bulgaria’s Nazi-allied monarchy during World War II: British officer Frank Thompson, whose story Ghodsee initially heard from the late physicist Freeman Dyson, and 14-year-old Elena Lagadinova, the youngest female member of Bulgaria’s armed anti-fascist resistance.

Ghodsee first met Lagadinova in 2010, while she was in Bulgaria conducting interviews for what would become her eighth book, Second World, Second Sex: Socialist Women’s Activism and Global Solidarity During the Cold War, which also included research with women and archives in Zambia. Lagadinova, who passed away in 2017, is one of the five subjects of Red Valkyries, along with the Ukrainian sniper Pavlichenko; Alexandra Kollontai, the aristocratic Bolshevik whose works Ghodsee discusses in her podcast A.K. 47; Nadezhda Krupskaya, the wife of Vladimir Lenin and an influential figure in her own right; and Inessa Armand, Lenin and Krupskaya’s close comrade and a talented polyglot.

In July, Kristen Ghodsee was appointed Department Chair of Russian and East European Studies. She reflects on the department’s future, particularly in light of the surge in interest in Eastern Europe brought on by the war between Russia and Ukraine: “I am really interested in creating more content that looks at the culture, history, and society of different East European nations, including Ukraine,” she says. “I think there’s a real hunger for knowledge about this part of the world and, as chair, I’m hoping that we can maintain our program but also build in some new components to the major.”

The department is currently in the process of bringing in a Ukrainian Fulbright scholar, as well as three doctoral candidates from Ukraine whose studies have been disrupted by the war. Ghodsee says that she hopes there will be more opportunities, especially in Western media, for scholars from the country to share their own stories.

While working on Second World, Second Sex, Ghodsee also published three other books, including the popular Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence, which originally came out in 2018 and has since appeared in 15 international editions and in 14 languages, including those of several former socialist countries in Eastern Europe. Her 2011 book, Professor Mommy: Finding Work/Family Balance in Academia, which Ghodsee co-authored with Rachel Connelly, her colleague at Bowdoin, was inspired by her own experience of navigating the academic job market as a new mother.

Red Valkyries is also a popular book, ending with nine lessons that contemporary audiences can learn from the lives of the book’s revolutionary subjects. The timing of the book’s publication—shortly after the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade—throws these lessons into even sharper relief. “Roe v. Wade shows very clearly that you can change a law, but if you don’t actually change the underlying cultural context or social context within which women gain those rights, then you can just overturn that law, even after 50 years,” Ghodsee says, explaining that the socialist feminists profiled in Red Valkyries fought for social change that doesn’t merely fold women into the prevailing power structure.

Stepping Outside of the Familiar

Like her interest in Eastern Europe, each of Ghodsee’s books has emerged from a confluence of factors: curiosity about the world, conversations with people, and being in the right place at the right time. For instance, her 2021 book Taking Stock of Shock: Social Consequences of the 1989 Revolutions, co-authored with Mitchell Orenstein, Professor and Graduate Chair of Russian and East European Studies, began as a debate in Williams Hall over a blog post.

“I’m the poster girl for ‘unplanniness,’ if that’s a word,” Ghodsee reflects. “The books—to me, the best ones—they emerge organically.”

But what’s consistently defined both her life and career is her willingness to step out of her familiar surroundings and into the everyday lives of others. “I’m constantly pushing myself out of my comfort zone and constantly challenging myself to see the world through a different set of eyes,” she says.

While Ghodsee returns to the physical classroom this fall for the first time since March 2020, her current research on Cold War-era typewriters—part of a work-in-progress on the material culture of communism—will eventually take her back to Eastern Europe, where she’ll track down more typewriters and more people with stories to tell.