OMNIA Q&A: The 55th Anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

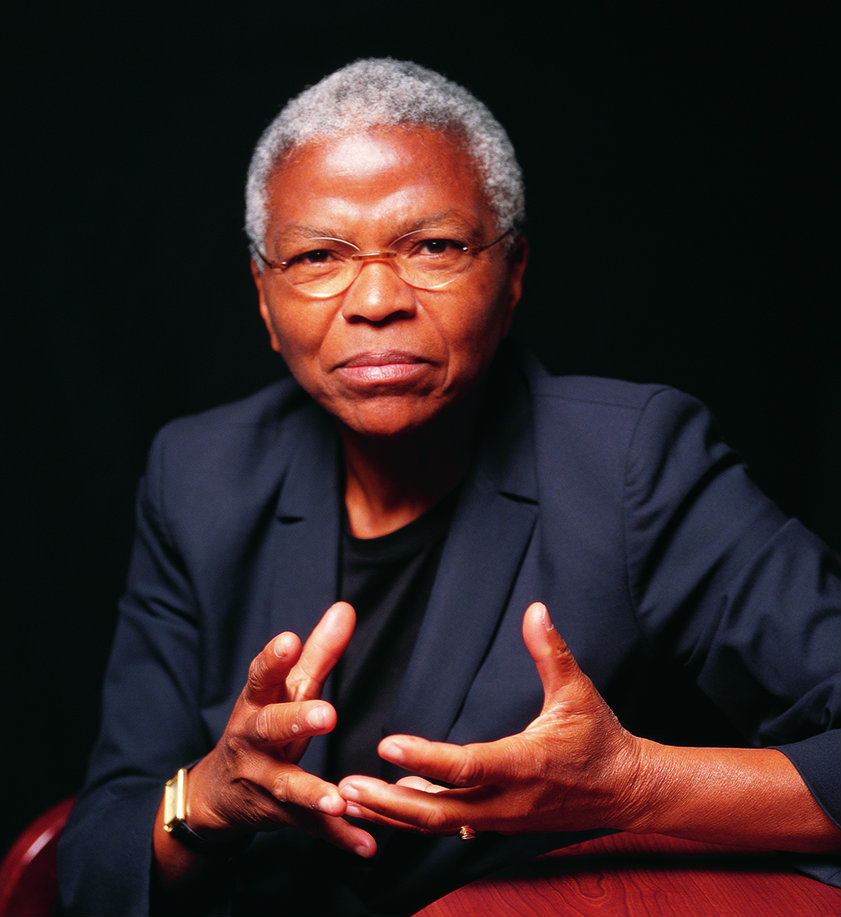

Mary Frances Berry, Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought and a professor of history and Africana studies, discusses the history of civil rights legislation and where 1964’s bill fits in.

What are the earliest examples of civil rights legislation in the U.S.?

After Congress passed the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, it enacted a civil rights act in 1866 that made Blacks citizens and supposedly gave them the rights to make contracts and get married, among other things. It was passed because southerners had immediately started a backlash against emancipation, issuing a series of regulations called Black Codes. This put Blacks back in a position of peonage, and tied them to employers—in many cases the same people as when they were slaves. White folks tried to apprentice ex-slave people's children and pretend there was some agreement to do it, so as to re-enslave them.

A lot of the northerners, the Unionists, were very upset, which is why they passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866. However, there was a huge debate in Congress about whether that law could in fact make Blacks citizens without the Constitution being changed, since the Dred Scott Decision stated that anybody who had come to the U.S. as a slave could never be a citizen; and about whether the act could be repealed if the white Confederates ever took over the national government. So the Unionists moved to enact the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship without regard to previous conditions, servitude, et cetera. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 is still on the books.

The Reconstruction era saw the rise of several different factions. Can you describe the political atmosphere of the time?

Ex-Confederates immediately started trying to overthrow Reconstruction legislation. This is where the Ku Klux Klan and the Knights of the White Camellias and other white supremacist organizations come into play. By 1869, Reconstruction was actually over everywhere except Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana, where it did not end until 1877. Everywhere else, the white supremacists pretty much took over.

In Congress, people like Senator Charles Sumner, from Massachusetts, and Representative Thaddeus Stevens, from Pennsylvania, continued to try to warrant maximum rights for Blacks and to protect them. The Justice Department in Washington tried to enforce punishing the white supremacists, but to no avail. In most cases, even when they arrested somebody or prosecuted them, the judge and jury would not convict them. It's much like today when we see police officers unnecessarily kill Black people and you can't get them prosecuted. Today we can get civil damages in these cases, but at that time, basically nothing would happen.

Sumner had the idea that a Civil Rights Act should be passed that would permit Blacks to use public accommodations. The Act was passed as a tribute to him after he died in 1875 but Congress took out the school provision. In 1883 the Supreme Court declared the Act unconstitutional and segregation in public accommodations continued.

In South Carolina, where there were more Blacks than whites, they were able to elect Blacks to the state legislature in 1868 and send Black members to Congress for the first time. In Mississippi and North Carolina, you also saw some Blacks being elected. And those state legislatures passed laws that changed the state and its public institutions. For example, there had never been public school systems in the South like the comprehensive ones that existed in the North. So these new legislators set up systems to provide universal public education in those states. They also set up institutions for the mentally disabled, and for people who had no ability to support themselves.

Was the 15th Amendment, designed to end voter discrimination, upheld on a societal level?

The 15th Amendment did not actually give people the right to vote—it just said you couldn't interfere with the right to vote for reasons of race and previous condition of servitude. And there was a whole dispute about what the language meant. As far as the 19th Amendment goes, granting women suffrage, there were a lot of Black women who, along with white women, worked to get that amendment. But in most cases, in the areas where white supremacy reigned, all Blacks were punished if they tried to register. White supremacists abused Blacks using all kinds of discriminatory means, including violence.

It was not until the civil rights movement in the 20th century that Congress passed a voting rights act in 1965, that the right to vote was protected by the federal government.

Who were the major players involved in getting the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed?

With all of the protests growing out of the first Montgomery bus boycott, which spread to sit-ins and marches, and then the March on Washington in 1963 with the labor movement, the president was forced to take notice. John F. Kennedy at first did not take the Civil Rights Movement seriously.

I wrote about it in a book called, And Justice for All, which is a history of the Civil Rights Commission. He and Bobby Kennedy thought that Martin Luther King would run out of steam. But by 1964, when people said "civil rights," they usually meant "Martin Luther King." There were people like Aaron Henry, who was the NAACP chairman in Mississippi, who was a stalwart on the issues and in protecting people, but nobody knew any of these people. So it was Martin Luther King whose face was on Time as Man of the Year. It was Martin Luther King who's standing there in the bill passage picture.

They also were worried about the Democratic senators from the South (Democrats controlled the politics in the South at that time, not Republicans as today)—that they would not confirm justices and go along with any plans and programs that President Kennedy had, so they had to be at peace with them.

It took JFK getting assassinated to finally get the bill passed. When Lyndon Johnson became president, he made it a must-pass bill, and in the reaction to the assassination, and the fact that Johnson was a skillful manager of legislation, he was able to get bi-partisan support for it, and got the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed.

How did media affect the civil rights movement in the 1960s?

Everybody across America used to watch the evening news, which gave the public a front-row seat to the violence at events like the Birmingham Campaign, when police dogs chased and bit Black youth protesters. We didn't have social media, but we had newspapers that people read. It wasn't something that somebody could pretend like it didn't happen or argue it away. The Kennedy administration was forced to draw up a bill to address all of the issues that the protesters were complaining about, including segregated public accommodations and voter suppression.

During that time, three civil rights workers, Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman, were killed by white supremacists, and that became a national and international story. And what made this story so powerful was that it crossed racial lines. Lots of Black people had been killed even before this and continue to be killed with not as much of a reaction, but having this done at this time to these people who were obviously innocent outraged people all across the country.

If you were in a southern town, most of which were segregated, the major media would be owned by somebody who supported segregation. There were papers, though, in some of the towns that were owned by people who would be loosely called liberals. The Nashville Tennessean was such a newspaper, and the Greenville Delta Democratic Times in Mississippi, whose editor, Hodding Carter II, won a Pulitzer in 1946 for his coverage.

How effective was the Civil Rights Act of 1964? What is its legacy?

Immediately there were people who went to places to try to eat or stay at a hotel, and were rejected. The Title 6 section in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 says you shall not give federal funds to institutions that discriminate on the basis of race, religion, or national origin. That provision has never really been implemented. There are studies where researchers have followed and monitored the amount of desegregation that exists, and there's very little in the schools in the country. We call segregation racial isolation. And we also know that in higher education, most institutions have not achieved the kind of goals that we hoped for in terms of admitting slave-descendant African Americans who were the target of these laws that were passed.

You also see continuous efforts to keep people from voting because of the way the people who are trying to suppress their vote think they will vote. And we see housing discrimination, even though we have a Fair Housing Act of 1968 passed after Martin Luther King’s assassination.

Many civil rights leaders thought that if we got legislation passed it would lead to equality and freedom and opportunities without discrimination, that the laws would be enforced and everything would be fine, and then people will give up all their old racist attitudes. But the question is: how do you get people to change their minds, and how do you get people to do the right thing? And there has to be some continued pressure in order to get that done.

But there's a hope that attitudes will change. Hope that someday people will understand that we shouldn't have racial segregation in the schools, and someday that people will understand that higher education institutions ought to admit and educate more Black people. But it hasn't happened yet. The laws are important, and we'd be worse off if we didn't have them, because otherwise there'd be no recourse at all for people who are harmed and abused.