Looking to Corporations to Learn About Religion

Jolyon Thomas, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, investigates the interdependent roles of corporations and religion.

In 2018, Jolyon Thomas and a colleague visited the Panasonic Museum in Osaka, Japan. Upon arrival, they were greeted by a larger-than-life statue of the founder of the company, Kōnosuke Matsushita, followed by a Japanese character in enormous font that read “michi,” which translates to “the way.”

“As scholars of religion, that character was really striking because that’s pretty much the primary metaphor that’s used for describing religious practices in English. For the longest time, Buddhism was described as the Buddhist path, and the Japanese tradition called Shinto is literally the ‘Way of the Gods,’” explains Thomas.

Inspired by this moment, Thomas, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, recently co-authored an article in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion titled, “Why Scholars of Religion Must Investigate the Corporate Form.” The authors look to genealogies of Japanese corporations like that of Panasonic, a multinational electronics company with more than 100 years of history, to highlight how these companies generate missions, families, individuals, and publics—similar to religions. Alongside Thomas, the authors are Levi McLaughlin of North Carolina State University, Aike P. Rots of the University of Oslo, and Chika Watanabe of the University of Manchester.

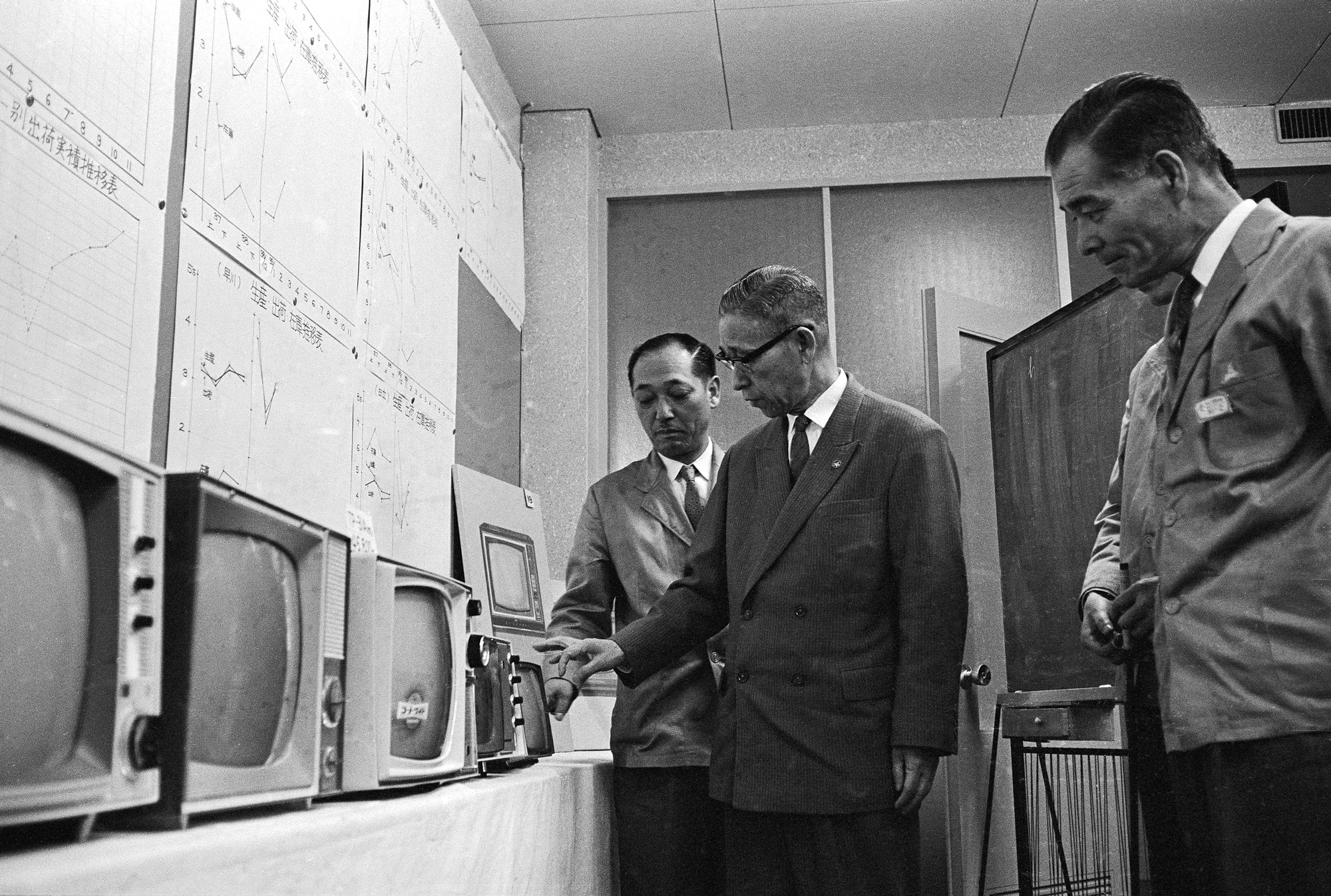

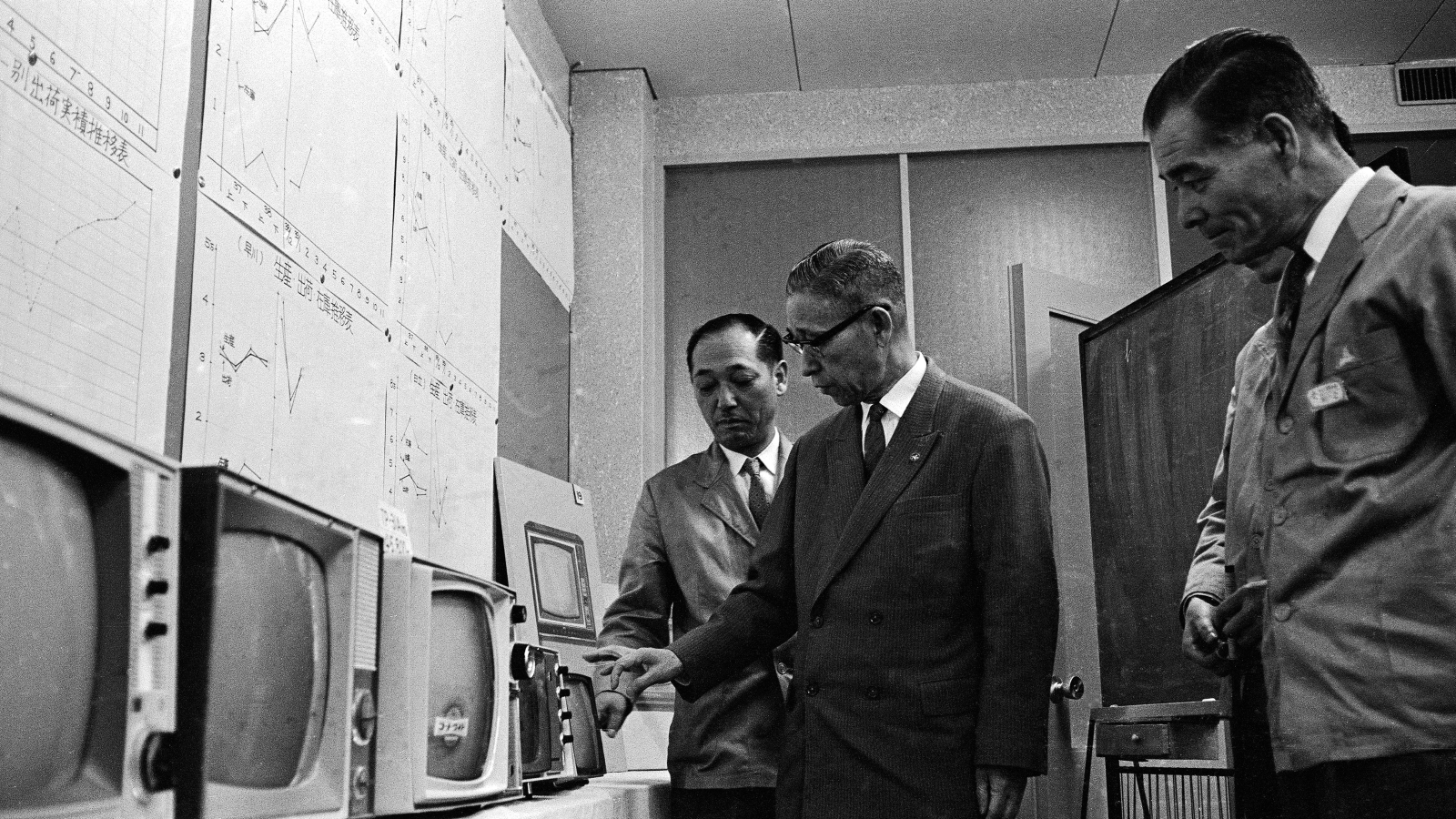

The Panasonic Museum is set up with multiple stations that depict a moment in Matsushita’s life alongside a photo and a small piece of paper for visitors to take with them. In their article, Thomas and co-authors describe the journey through the museum as “a pilgrimage” and the papers as “talismans.”

“The takeaway papers look almost exactly like talismans that you get at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. The papers have an aphorism on them, which is a quote from Matsushita’s writings,” says Thomas. “There is a functional similarity with religion where you’re getting these words of wisdom from this profound figure who is clearly depicted as a leader who utterly changed the world.”

In fact, Matsushita’s guides on how people should engage in business etiquette, train new employees, and so forth have been borrowed and reproduced by other corporations. Thomas adds, “It’s not an overstatement to say that his vision for what corporations do for society has become adopted and understood by Japanese as being normative. Like this is what corporations are supposed to do.”

Like many religions, corporations demand a great deal from human bodies. An extreme example of this in Japanese society is the phenomenon called karoshi, which is death from overwork.

“Any collective enterprise depends on multiple human bodies gathering together in pursuit of a shared agenda. And usually when that happens, the collective ends up superseding the needs of the individuals,” says Thomas, who is working on a book on the topic of religion in public schooling in Japan and the U.S.

Thomas says examples of how the collective is prioritized over the individual include sports teams, where people will exhaust or injure themselves so the team can do well, or armies, where individuals are trained to sacrifice themselves in devotion to abstract ideals, like the nation.

“If you slip up, then the corporation may disavow you,” Thomas adds. He mentions the recent news story of Jerry Falwell, Jr., a leading figure in the evangelical Christian movement, who was asked to resign as head of one of the largest Christian universities in the world due to a personal scandal. “Falwell is expendable from the perspective of the corporation.”