Locked Down and Opening Up

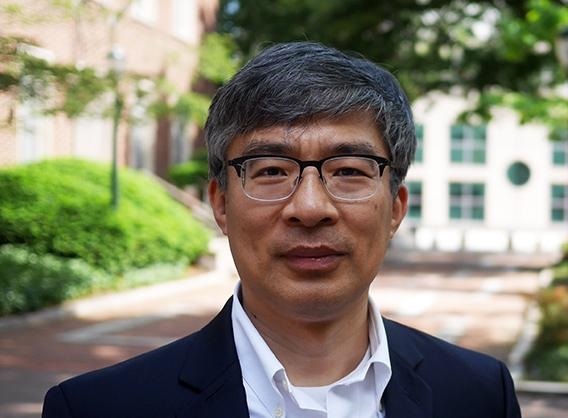

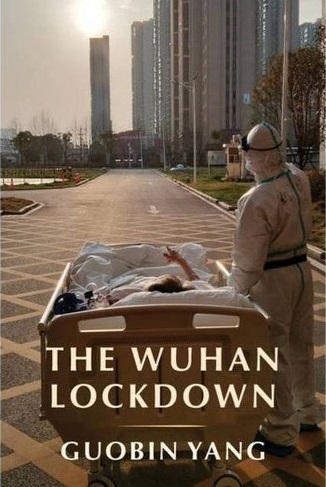

In his new book, Guobin Yang, Grace Lee Boggs Professor of Communication and Sociology, highlights the online diaries shared by Wuhan residents early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keeping track of all the expletives in the “Wuhan swearing woman” recording is no easy feat. In an obscenity-laced, rapid-fire tirade that went viral on the Chinese social media app WeChat in February 2020, an anonymous woman spends two and a half minutes berating the managers of her residential complex and neighborhood supermarket for swindling community members instead of supporting them during an unprecedented crisis.

The ferocity of this audio clip, which was captured a month after the Chinese government completely shuttered Wuhan—the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak—struck a collective nerve among the 11 million weary residents who were demoralized by weeks of forced isolation with no end in sight.

“It had so much power and such cathartic effects for a city in distress, like suddenly all these people who felt so much fear and uncertainty had this outlet for their own emotions,” Guobin Yang, Grace Lee Boggs Professor of Communication and Sociology, says of the speech—one of dozens of social media posts featured in his new book, The Wuhan Lockdown.

Yang uses his book to tell the stories of “ordinary people” as they navigated the world’s first COVID-related lockdown from January 23 to April 8, 2020. A scholar of digital culture and contemporary China, he saw an immediate spike in daily diary-style posts on WeChat and another social media platform, Weibo, at the lockdown’s onset, and recognized them as a rich resource for social science research. Glued to his screen for more than two months, he amassed an archive of 6,000 entries, ultimately choosing 46 diarists from all walks of life to appear in the book.

“It is important to give a voice to ordinary people, particularly for this kind of extraordinary historical event,” says Yang. “All kinds of official histories and narratives will be written about this lockdown, but the people on the ground will not feature very visibly in those, and their stories about resilience, perseverance, sacrifices to protect families and communities, hardships, fears, love, friendship, tragedy, and protest need to be told.” He laments that a March 2020 New York Times piece titled “The Quarantine Diaries” showcased writings from homebound individuals around the world—without including a single word from Wuhan, “the mother of all COVID diaries.”

Like certain social media outbursts did for Wuhan residents, working on this book provided a means of catharsis for Yang, who grew up in China and still has relatives there. Deeming a conventional academic text inadequate for addressing an event that touched him and his loved ones so deeply, he took a “humbler approach” by sharing citizens’ firsthand accounts of their experiences and rounding them out with historical and cultural context. The diarists spotlighted run the gamut from famous—like controversial author Fang Fang and feminist activist Guo Jing—to virtually unknown—like the volunteer driver who delivered donations to frontline healthcare workers and the animal lover who coordinated the rescue of thousands of pets stranded at home without their owners.

Yang continues to follow many Wuhan residents’ social media posts today but says they have decreased in volume and urgency since that initial 76-day deluge, which had an “important but unintentional social effect.”

“The proliferation of all the diarists’ different voices built a sense of national solidarity during the Wuhan lockdown in a way that Twitter or Facebook did not in the United States,” he says. “These diaries brought a sense of togetherness, produced powerful emotional effects, created online discourse, and helped others to release their own feelings. In this way, they are not just records of history. They actually made history.”