Listen on Repeat

Mary Channen Caldwell, Assistant Professor of Music, brings together over 400 devotional Latin refrain songs from the Middle Ages in her new book, the first to explore the medieval refrain in song outside of vernacular contexts.

While working on a directed study on medieval dance in graduate school, Mary Channen Caldwell, Assistant Professor of Music, kept coming across references to Latin songs with refrains. In contemporary music, the refrain refers to a song’s repeated lines, or its chorus—think of the part that you somehow always remember and sing along to.

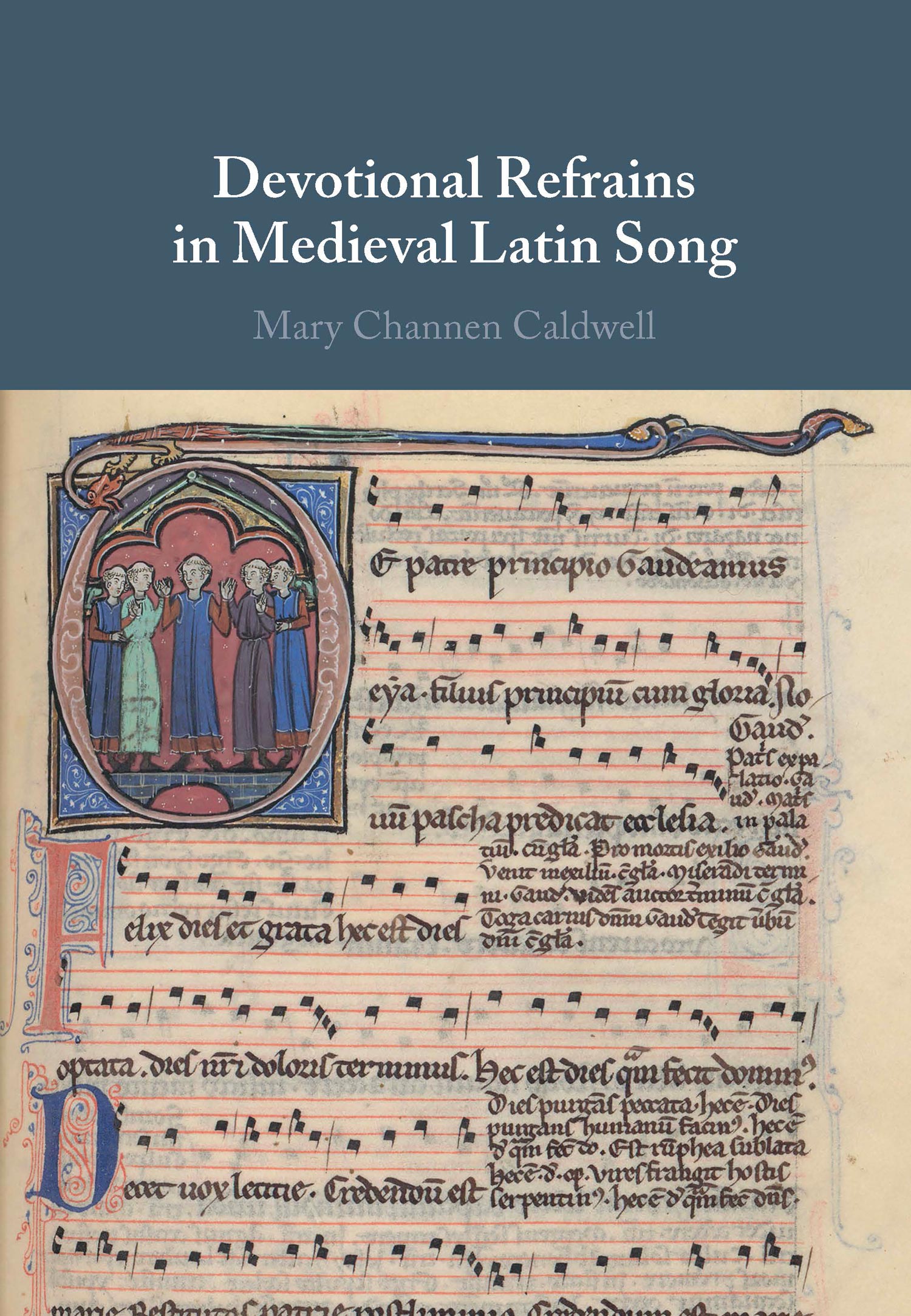

But the refrain in the repertoire that caught Caldwell’s attention is distinctive in a number of ways. “You can have the same refrain in different songs, for example,” Caldwell says, explaining that there is more to the medieval refrain than its association with dance. Her new book, Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song, explores these possibilities, tracing how the Latin refrains and refrain songs were created, transmitted, and performed.

Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song focuses on devotional songs that would have been part of the musical practices of the Latin-literate communities attached to churches, abbeys, and schools across medieval Europe. The book, which includes five chapters, as well as an introduction and conclusion, highlights the versatility of the Latin refrain as a devotional tool in these communities—and as an interpretive framework for modern-day scholars. Each chapter analyzes a specific aspect of the Latin refrain, from its relationship to medieval notions of time to the refrain’s role in the formation of devotional communities. To carry out her study, Caldwell compiled and studied over 400 vocal works from dozens of manuscripts located in archives in France, Italy, Ireland, and elsewhere.

The book considers songs chiefly from the 11th to the 16th century, first examining the relationship between the Latin refrain and perceptions of time in the Middle Ages. “Latin refrain songs and the refrains in them negotiate different poetic and musical temporalities,” Caldwell explains. While medieval Christians understood time through liturgical celebrations like Christmas or Easter, Caldwell says that Latin refrain songs merged the liturgical calendar with the seasonal experience of time—spring, summer, winter, and fall. For instance, one of the earliest associations of the New Year, or annus novus, with January 1 appeared in a collection of Latin refrains that connected “the idea of the new year with ideas of the Feast of the Circumcision, which was the liturgical feast of January 1,” Caldwell says.

Another notable feature of the Latin refrain appears in the manuscripts themselves as inscriptions, rubrics, and marginalia. This is significant for both scholars studying medieval music and those trying to reconstruct medieval cultural traditions. Caldwell says, “One of the hardest things about studying medieval music is that we don’t know how it’s performed. We can make educated guesses—we can study the theoretical treatises and make interesting hypotheses—but at the end of the day, there’s a lot that we just don’t know.”

The annotated manuscripts of many Latin refrain songs shed some light on these unknowns, sometimes indicating who would sing what or even explaining why a collection included a certain song. One of the sources that Caldwell examines—the Moosburger Graduale, a manuscript containing Latin chant and devotional songs from 14th-century Moosburg, Germany—includes a preface written by the dean of the local church’s song school. “He arranged for these songs to be copied into this book and he talks about how they’re for the choristers because otherwise they would sing songs that maybe weren’t so appropriate,” Caldwell says. “Textual introductions to songs are pretty rare, but this gives us insight into the medieval perspective on this repertoire from someone who is actively involved in the musical life of, in this case, choir boys.”

Songs like those in the Moosburger Graduale would have likely been adapted to other contexts. A key finding of Caldwell’s research, then, is that Latin refrains were rarely fixed, despite their repeatability. “From the 12th to the 16th centuries in Europe, you have these refrains that appear across multiple songs and each time they appear in any song, you have the possibility of remembering what it was in the original song and also creating a new context for that same refrain,” Caldwell says, explaining how the Latin refrain moved across time and space while simultaneously creating “networks of memory and allusion.”

“Some of these songs continue to be sung for hundreds of years and a couple of them actually end up getting translated into vernacular and sung as Christmas carols,” Caldwell explains. “These are songs that have had a lifespan of millennia and that’s really unusual. But this speaks to the idea that these little units of text and music were somehow meaningful—they were meaningful enough to continue being part of traditions that in other ways had changed dramatically.”

Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song is the first book to offer such a comprehensive study of Latin refrains, but Caldwell notes that there is still much more to be said about these little units of text and music: the Latin refrain “really deserves a bit more time in the spotlight.”