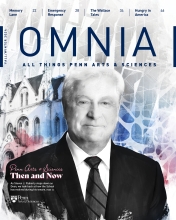

Hungry in America

Penn Arts & Sciences alums are taking on the challenge of food insecurity locally and on a national scale.

America is one of the wealthiest nations in the world, and yet roughly one in seven adults—more than 47 million people—lives with hunger, according to the latest data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Unraveling and ameliorating the problem of insufficient access to food in the United States is complex, frustrating, life-changing work, and it’s an area where Penn Arts & Sciences alums are actively contributing, through their own initiatives or by joining those already tackling the issue.

Lack of available food is not the problem, says Julia Luscombe, C’10, W’10, who heads strategic planning at Feeding America, the largest charity working to end hunger in the U.S., in partnership with a nationwide network. “We have the resources, technology, and knowledge in this country to make hunger a non-issue,” she says, but systemic inequities and inefficiencies have erected obstacles to getting food into the hands of those who most need it.

More than a third of the food produced annually in the U.S. goes unsold or uneaten, so a big part of Feeding America’s work revolves around food “rescue”—collecting and redistributing the surplus. Feeding America expects to collect 7 billion pounds in 2024.

At the local level, too, Penn alums are involved in a range of efforts to combat food insecurity. In San Francisco, Jason Nunan, C’80, pivoted during the pandemic from fine dining to working with a food bank, which he continues today. In Philadelphia, Alex Imbot, C’20, and Eli Moraru, C’21, have partnered with neighbors to reinvent the corner store, to get residents access to fresh, healthy meals using their public benefits.

“It takes a collective effort to reimagine our food system, to work together, to collaborate, to harness the power of our communities,” says Moraru. “By addressing food injustice together, we have the ability to lift up our communities and solve nutrition insecurity.”

The Ideal Corner Store

Distributing USDA food boxes on the corner of 30th and Moore Streets in South Philadelphia during the pandemic, Imbot and Moraru had plenty of time to chat with neighbors about the failures of our current food system and to envision the perfect corner store. This winter, those dreams will turn brick-and-mortar with the opening of The Community Grocer a few miles away in the Cobbs Creek section of West Philadelphia.

Before volunteering together, Imbot and Moraru seemed on different trajectories. Imbot was focused on environmental justice and had spent years working with residents of the city’s Grays Ferry neighborhood, the site of a 2019 oil refinery explosion. Moraru was interested in politics and had been active in voter registration. As they handed out food, both were struck by how this top-down government solution to address hunger failed to understand the nuances of daily life.

Many neighbors, they discovered, were uninterested in free boxes of onions, apples, chicken, cheese, and yogurt. “The raw bulk ingredients didn’t add up to a recipe,” says Imbot. Instead, people would go to the corner store and spend their Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) dollars on what was readily available: ultra-processed foods like chips and soda.

Imbot and Moraru learned that food stamps—or SNAP, as the program is now called—cannot be used to purchase hot prepared food. “You can buy Skittles for breakfast with your food stamps,” says Imbot, “but not scrambled eggs.” The neighbors, Moraru recalls, “kept saying to us, ‘I wish I could use my EBT for a hot, healthy, delicious meal, but I can’t.’ Alex and I just thought that was ridiculous.”

Rules of SNAP, or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, specifically prohibit “you buy, we fry,” says Imbot, meaning that someone cannot go into a store and purchase raw chicken and then have the people in the back cook it, a popular model in many under-resourced neighborhoods. Yet Moraru and Imbot wondered whether “you buy, they fry” might be an option. In other words, Moraru says, “you buy an EBT-eligible meal kit at our store and somewhere else, off-premises, it gets cooked.”

It takes a collective effort to reimagine our food system, to work together, to collaborate, to harness the power of our communities. By addressing food injustice together, we have the ability to lift up our communities and solve nutrition insecurity.

That became the model for The Community Grocer, an idea that in 2022 earned the President’s Sustainability Prize, a transformational $100,000 contribution from Penn. Others jumped on board, including Chef Z (Aziza Young) as culinary director and architect Richard Stokes, who is designing the space. Priced out of South Philadelphia, Imbot and Moraru purchased the Cobbs Creek property and spent four months talking with neighbors, meeting block captains and community organizers, and sharing their vision.

When The Community Grocer opens in early 2025, it will receive, store, sort, chop, and marinate to create raw meal kits. Customers will select a kit from the fridge and pay for it with SNAP or any other kind of payment. They’ll then have the option to walk out the side door and back into a separate part of the building, operated by a separate nonprofit, where they can present the kit and swap it for one that is hot and ready to eat. “Their ingredients go toward the next batch, so effectively the transfer can be done faster than microwaving an entree,” says Imbot. As long as the preparation and cooking entities are separately owned and operated, the model is legal and compliant.

Menu tasting is underway and a team of 45 neighborhood residents will be hired over the next few months. Most importantly, Moraru says, they will be “providing the neighbors with the toolkits, funding, and everything necessary for them to operationalize” a new kind of corner store, one focused on what the community has said it needs.

Community-Led Change at Scale

Julia Luscombe, C’10, W’10, heads strategic planning at Feeding America, the largest charity working to end hunger in the United States.

Courtesy of Julia Luscombe

Julia Luscombe, VP for strategic planning and portfolio management at Feeding America, always envisioned working in an area of social impact. “What is surprising to me, though, is to be working on hunger relief in the U.S.,” says Luscombe, a graduate of the dual-degree Huntsman Program in International Studies and Business administered by Penn Arts & Sciences and Wharton. “If you had told me in college that hunger would be an issue of this magnitude here, I would not have believed you. I would have seen myself doing that work in other countries.”

One factor contributing to this reality, she says, is globalization. “It has impacted what is required to build a more equitable and sustainable food system: thriving, resilient local economies. And so, all these challenges of food security that you hear about globally we face in the U.S. as well, where, ironically, some of the highest rates of food insecurity are in rural areas where food is produced.”

To solve the “huge gaps in food access,” she says, will take deep engagement and support for community partners to build flourishing local food systems. “Without targeted investments that meet the unique needs of communities, we risk letting some people fall more behind,” she says.

A national organization, Feeding America works as a catalyst for local, community-driven solutions, partnering with a network of food banks that distribute regionally to food pantries and community organizations across the U.S. In her role, Luscombe is supporting network members in developing a shared five-year strategy informed by local and regional listening sessions—centering the voices of the people they serve.

The goal, Luscombe says, is “to have everyone in this collective network, with its incredible reach and potential for impact, all rowing in the same direction, with the needs of people facing hunger setting that direction.”

It was like the circus coming to town. We literally would pop up tents, block off two ends of the street, and an 18-wheeler truck with 27,000 pounds of food would roll in. There were cases upon cases of fresh fruit and vegetables, and we would make a production line, assemble 15- to 30-pound bags of food, and hand them out.

For food sourcing, Feeding America partners with national producers and then works to coordinate food rescue locally. “We and the network are being increasingly intentional in how we are sourcing food, for example working with growers led by people of color,” says Luscombe. “When donations aren’t sufficient and food has to be purchased, we’re thinking about how we can support local growers, local companies, to keep the dollars within the community whenever possible.”

Luscombe says she jokes with her friends that she studied international business and is now working in “domestic non-business.” Having spent time abroad, though, working on economic development strategies in Ecuador, she says, “I realized how many challenges there were back home and how I could contribute to helping the U.S. better model the solutions we often try to promote internationally. Now, to be working at a national organization that’s coming up with strategies together with our network, with people facing hunger, and thinking about how we can catalyze community-led change at scale is really exciting.”

A Pandemic Pivot

Jason Nunan, C’80, has spent most of his career working with food. Until four years ago, his focus was squarely on fine dining. As executive director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s restaurants and later, general manager at Michelin-starred restaurants in the Bay Area, Nunan took care of a clientele who willingly paid a premium for white truffles and wagyu rib-eye.

The goal is to have everyone in this collective network, with its incredible reach and potential for impact, all rowing in the same direction, with the needs of people facing hunger setting that direction.

That all changed when, at the beginning of the pandemic, Nunan’s restaurant went into lockdown and the entire staff was furloughed indefinitely. Sitting at home and, as he readily admits, “spending more time on social media than I should,” he noticed that a chef friend was posting pictures of himself distributing food with the San Francisco-Marin Food Bank.

“I thought, ‘Well, I’ve been around food all my life—this is my connection,’” says Nunan. “I’m tired of sitting here watching Tiger King and scrolling through Instagram.” Nunan began volunteering four days a week and “fell in love with it.” The food bank’s 240 pantries in San Francisco and Marin County (which feed 50,000 people a week) had closed due to the pandemic, so pop-up pantries were being organized. Nunan happily jumped into the fray.

“It was like the circus coming to town,” he says. “We literally would pop up tents, block off two ends of the street, and an 18-wheeler truck with 27,000 pounds of food would roll in. There were cases upon cases of fresh fruit and vegetables, and we would make a production line, assemble 15- to 30-pound bags of food, and hand them out. The criteria for eligibility was, ‘Do you live in San Francisco?’ If the answer was yes, then the next question was, ‘Do you need food?’ And if you said yes, we gave you food.”

Jason Nunan, C’80, at a pop-up food pantry, one of many that opened during the pandemic when traditional food banks had to close.

Courtesy of Jason Nunan

When a fulltime community coordinator position came up, Nunan raised his hand. The first year, he remembers, was unusually rainy and he would return home soaked to the bone. “I honestly didn’t care,” he says, “because I felt like I was moving the needle just a little.” Four years on, he still feels that way. “I’m making a fraction of what I used to make, but I truly feel like I’m helping people,” he says. “Rather than selling $300 caviar, I am giving someone who might be living on nothing more than Social Security payments 23 pounds of fresh food. I can’t go back.”

The pop-up pantries, paid for by a pandemic funding spike that has since subsided, will wind down in 2025, and patrons will be encouraged to visit existing local pantries. Nunan’s job will shift to the permanent pantries, too. The need is very much still there. Before the pandemic, according to the food bank’s statistics, one in five people in the area was food insecure. The figure is now closer to one in four.

More than half of the distributed food comes from Farm to Family, a program set up by the food bank through which farmers can donate produce that would not sell in a grocery store—tiny apples, massive cabbages, ugly tomatoes. The USDA also contributes items such as frozen chicken and eggs, and private donors like Trader Joe’s and Safeway regularly give baked goods.

Nunan knows that, with its famously high cost of living, the Bay Area can be a tough place to make ends meet. Still, he has been surprised and moved by his encounters with those experiencing food insecurity. He feels compassion toward anyone who comes for a bag of groceries, “but what touches my heart even more is when someone like a working-age woman in her uniform comes up to get a bag. And you can tell she has run out from work on a break, and her job is not providing her enough money for groceries.”