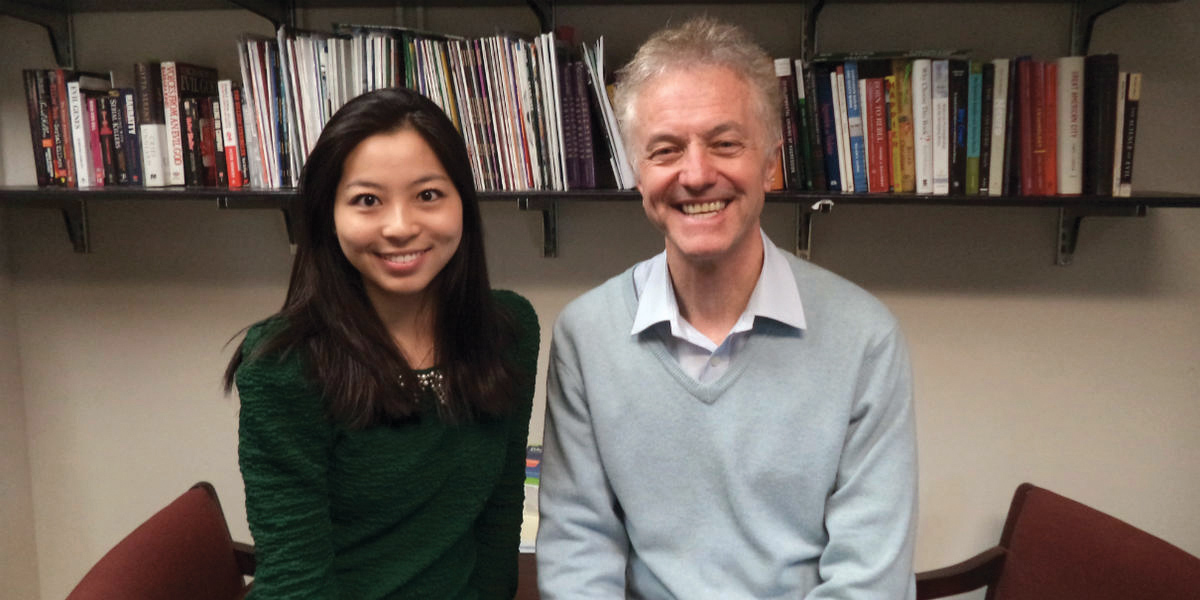

Olivia Choy, an assistant professor of psychology at Nanyang Technological University, led the research study when she was a doctoral student in the lab of Adrian Raine, Richard Perry University Professor of Criminology.

For a long time, some psychologists chalked up the gender gap in criminal offending to differential parenting.

“We give little girls toys and little boys toy guns,” says Raine, who holds appointments in Penn Arts and Sciences and the Perelman School of Medicine. “But this is not the complete answer. Biological variables like heart rate are at play, and the more we begin to pay attention to the biological contributions to crime causation, the more we may understand, and ultimately prevent, the higher crime rates in men.”

Choy’s study, “Explaining the Gender Gap in Crime: The Role of Heart Rate,” goes beyond traditional socialization theories to address the incomplete understanding.

The study examined data obtained from a subsample of 1,795 participants involved in the Mauritius Child Health Project. Children in the project were born between 1969 and 1970. They were recruited into the study from Mauritius, a tropical island in sub-Saharan Africa, when they were 3 years old.

The resting heart rates of 894 children were documented when they were 11 years old and were reviewed 12 years later when the children were 23-year-old adults. The heart rate data was evaluated alongside the study participants’ self-reported criminal activity and their official conviction records for criminal offending, including violent crime and drug-related crime.

The study found that resting heart rate accounted for five to 17 percent of the gender difference in crime.

Prior studies have shown that people with low resting heart rates seek stimulation to raise their arousal level to a more optimal one. This stimulation-seeking theory converges with a fearlessness theory, arguing that those with low heart rate have a low level of fear and may be more likely to engage in antisocial behavior, which requires a degree of fearlessness.

“One way to get that stimulation is by engaging in antisocial behavior,” Choy says. “Obviously, you can engage in prosocial behavior like skydiving, but another major theory connects low levels of arousal to low heart rate, reflecting a low level of fear in individuals. To commit a crime, you do need a level of fearlessness.”

Choy adds that the gender gap in crime is seen across time and across cultures. Differences in heart rates among male and female children are seen as early as 17 months of age: “You see it from 1 to 79 years, and even in newborn males who have lower resting heart rates than females.”

Both Choy and Raine believe that researchers need to look at the biological factors that cause the higher crime rates in men to ultimately prevent them from criminal offending.