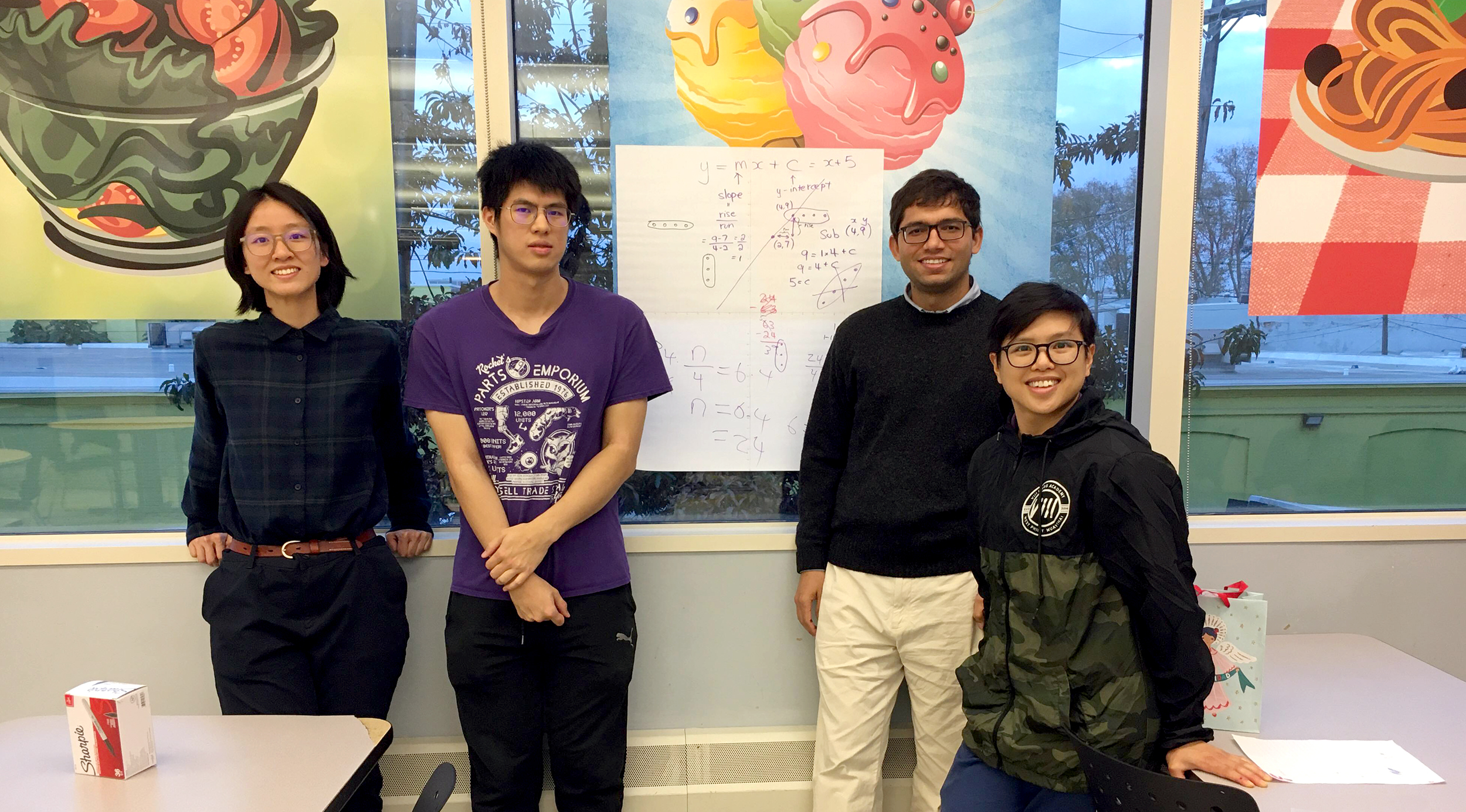

On a recent Thursday, Ph.D. student Marielle Ong took a break from her math research to bring several oversized cardboard Battleship game boards to West Philadelphia High School. She was there to run math circles—interactive, puzzle-based sessions—with a group of eight students, mostly ninth graders. Instead of calling out a letter and number, the students would need to aim at an opponent’s ship by writing an equation for a line that intersected with the ship’s location.

Much to Ong’s relief, the game was a hit. Many of the students even took their boards home to show their parents.

She’d had the idea for the activity after the Netter Center, Penn’s home for civic and community engagement, accepted a proposal for the math circles that she’d submitted in 2022. She’d been interested in finding creative ways to bring her subject to new audiences since the year prior, when she started teaching math to incarcerated people through a program run by Mona Merling, an assistant professor in the Department of Mathematics.

Though Ong knows that not everyone will become a mathematician, she believes everyone can benefit from learning to think like a mathematician: approaching problems creatively, testing out multiple solutions, persevering through struggle. “There’s no such thing as not being a math person,” she says. “I want people to be able to realize their potential in problem solving. With enough time and effort, you can do this.”

The Battleship game that Ong created is one of many innovative science and math communication efforts from Penn Arts & Sciences students and professors, who are drawing comics, creating games, writing articles, and more to move their specialties out of the university and into new communities. The efforts not only make the science more accessible, but they also help ensure that such work gains a life beyond the university classroom or lab, says Julee Farley, director of the School’s Science Outreach Initiative.

“People at the University are really doing important work that can change society, that can make society better,” Farley says. “But only if society actually knows about it.”

Community Connections

PennNeuroKnow (PNK), a blog created and run by students in the Neuroscience Graduate Group, is putting that idea into practice. Aimed at “breaking the brain down for everyone to understand,” the blog features weekly articles written by a rotating group of 17 contributors who choose topics ranging from explaining their own research or neuroscience in the news to debunking popular brain myths. A recent article, for example, refuted the popular idea that video games are inherently bad for children’s brains by discussing a study showing that some games can improve children’s cognition.

The blog editors ensure that anyone at an eighth-grade reading level can understand every piece they write and term they use, says Lindsay Ejoh, a neuroscience Ph.D. student and PNK co-editor. The site’s homepage features engaging images and short summaries to entice readers, and editors often work with writers to create charts and figures to illustrate complex topics. “We really want to make it as accessible as possible for everyone,” says Ejoh, who also shares her neuroscience work to more than 17,000 TikTok followers as @neuro_melody.

The work is about more than just teaching people fun and quirky aspects of the brain. It can have concrete, real-world benefits, too. In July 2019, PNK co-founder Carolyn Keating, GR’20, wrote a story for the site titled “When Your Brain Is on Fire,” which explained a brain disease called anti-NMDAR encephalitis, also known as autoimmune encephalitis, an illness Penn researchers first described in 2007. The post caught the attention of the International Autoimmune Encephalitis Society (IAES), a patient advocacy group for people with the disease.

The IAES asked to share Keating’s post on its website; a few months later, PNK announced an official collaboration with the society. The blog team now writes an article for the IAES website once per month, and IAES shares PNK articles that might be useful for its community. “We get a lot of engagement from that,” says Ph.D. student Catrina Hacker, PNK co-editor. “It’s patients living with this disease and their families just trying to understand the disease and also the brain more generally.”

Mathematical Media

For Merling, the motivation to bring math to the public stemmed, in part, from an experience as an undergraduate math student at Bard College. Just before graduation, she was one of four students from different majors asked to present her senior thesis to an audience of parents.

At the end of the presentation, a parent asked how Merling’s work could ever be useful. Merling recalls feeling perplexed at why the parent directed the question only at her. “We’re all just doing some beautiful scholarly work,” Merling wanted to tell the parent. “This is no different.”

Since then, she has prioritized outreach along with her math research. She found something of a kindred spirit in her fourth-year graduate student Maxine Calle, who has wanted to communicate the beauty of math ever since she discovered it herself as an undergraduate philosophy student.

This past summer, Calle was selected as an American Association for the Advancement of Science Mass Media fellow, a 10-week program that places math, science, and engineering students in a newsroom. Calle worked as an editor at The Conversation, a nonprofit news outlet written entirely by scientists. When her supervisors told her she could write her own piece, she jumped at the opportunity.

Calle’s first article described how she connected insights from two seemingly disparate math branches to solve an age-old theorem. For her second piece, co-authored with Merling, she adapted a comic she had previously illustrated to create colorful graphics and animations that visualize her research in algebraic K-theory, a field that connects to many areas of mathematics.

Merling and Calle also plan to create a video about K-Theory, at the request of mathematician Mura Yakerson, who runs the popular math YouTube channel Math-Life Balance and recently launched a series called “K-Theory Wonderland.” They hope to have the video finished by year’s end.

That kind of advisor support for outreach work is not always guaranteed for students, Calle says.

“Communication is something that I value,” she adds. “But academia doesn’t really train you to do it, and it’s not prioritized very often.”

Telling the Story of Science

Calle believes that strong science communication needs a solid and engaging story, a notion that also motivates Ryan Batkie’s work. Among his other responsibilities, Batkie, an instructor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy and a former high school physics teacher, guides physics graduate students on how to communicate their work to non-experts.

Many grad students have experience with public-facing events that involve explaining or demonstrating a physics concept. But that type of communication relies on what’s known as the information-deficit model: that people who don’t understand something simply need more information.

Batkie instead wants students to work more collaboratively with their audiences and bring them into the scientific process. He’s currently helping his students develop a version of their work that high school students could actually conduct from their classroom. “It’s way more about that story of how we went from not knowing to knowing than it is just packaging a fact,” Batkie says. “Science has value and we know things and it does help us live better.”

Batkie’s approach is an example of what Farley sees as the best kind of science outreach: two-way communication. Outreach efforts should inform a community while simultaneously being informed by what the community needs, she says.

In the past, most research was not shared beyond publication in an academic journal or conversation among experts, Farley adds. But more academics are prioritizing this kind of work now, focusing on the societal impact of what they do and communicating that to society.

“I don’t think it’s acceptable anymore to be that lone researcher who just studies whatever they want,” Farley says. “It’s more expected now that higher-ed researchers will do work that will have some greater impact on the large societal problems that we face as a world.” The mission is a serious one, but as Ong’s math circles show, the right way to tackle it can sometimes include fun and games.