Dorothy Roberts isn’t one to sit still. The George A. Weiss University Professor of Law and Sociology and Raymond Pace and Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander Professor of Civil Rights holds appointments in sociology, law, and Africana studies. Her new undertaking — The Program on Race, Science, and Society — is designed as an interdisciplinary initiative challenging social and life scientists to be more creative in their approaches to integrating race in their research. The program is a natural extension of Roberts’ current research and latest book, Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century, which attacks the notion that race can be categorized biologically. It’s an assertion Roberts says can only be addressed through sharing knowledge between the social sciences and humanities and fields like medicine, genetics, and neuroscience.

Roberts’ recognition as a scholar on race was catapulted after her article, “Punishing Drug Addicts Who Have Babies: Women of Color, Equality, and the Right of Privacy,” was published in Harvard Law Review in 1991. The article eventually evolved into her first—now widely taught—book: Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. But as a new professor, Roberts felt pulled between teaching law and her interdisciplinary approach to advocating for social justice. Penn represented an opportunity to bridge these interests. The Program on Race, Science, and Society, which recently launched with its premiere symposium, The Future of Race: Regression or Revolution?, is a prime example of this synergy. “We want to develop research projects to address concrete issues,” says Roberts. “Like, what is the relevance of race to studying why African Americans have a higher rate of infant mortality? How can we ever hope to solve a problem like this if we just assume the cause is genetic?”

Roberts says the culture of defining race in biological terms is often unexamined, and therefore especially dangerous. “There is a device currently used for measuring lung capacity called a spirometer that actually has a button for race, which is a holdover from the belief that enslaved Africans innately had lower lung capacity,” says Roberts. “So what information should a doctor put in for a patient who identifies as black, but most of whose ancestors come from Europe or Asia?” In addition, new products and services like race-specific pharmaceuticals, ancestry testing, and widely publicized books like A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race, and Human History, by former New York Times journalist Nicholas Wade, only reinforce false concepts of race, says Roberts. “We need to tear down these disciplinary silos and have an honest discussion about humanity. It’s the only way we will ever make any progress in the study of race and racism,” she says.

Roberts’ scholarly pedigree is the result of a life of witnessing tumultuous social change and diverse cultural interactions. Somewhere between her accounts of huddling into the basement of a local church for civil rights meetings as a child and her sojourn across Central America as a college student with nothing but bus money, it becomes clear that the line between her life story and her academic career is non-existent. From her beginnings as a young girl dreaming of becoming an anthropologist, to her decision to join her father in the role of professor, it’s a journey that stretches across the globe and into the lives of those she has encountered along the way. Join us as we follow Dorothy Roberts through time.

BEGINNINGS

Hyde Park. Chicago, Illinois. 1967. An 11-year-old Dorothy Roberts presents a book report on Black Power: The Politics of Liberation. Charles Hamilton, the co-author, is her father’s colleague at Roosevelt University. Soon, U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy launches his anti-Vietnam War presidential campaign against Lyndon B. Johnson. Dorothy goes door to door after school, handing out fliers in support. The city is buzzing. Up and down the streets of Hyde Park, neighbors hold meetings as proponents of civil rights. They sit hunched around TVs that play footage of the ugliness in the South. The wheels are in motion. Things are happening. And she has a front row seat.

A SECRET PLACE

Education was everything in the Roberts house: a huge Victorian with a locked door on the third floor. The room felt extra-mysterious, because it was above where they slept, detached from everyday life. When her parents were occupied she would drag a chair up and get on her tip-toes to reach the old-fashioned key that hung on a nail. Upon entering her father’s study, there was an almost impossibly large wall of books: ethnographies, arranged by continent. She sat for hours, reading through tales about foreign lands. There were many books about India, where her father, ever the adventurous type, had lived as a teenager with his aunt who was a missionary. She learned how to breathe correctly from a book about yoga and wondered how so many people in the States could be doing it wrong.

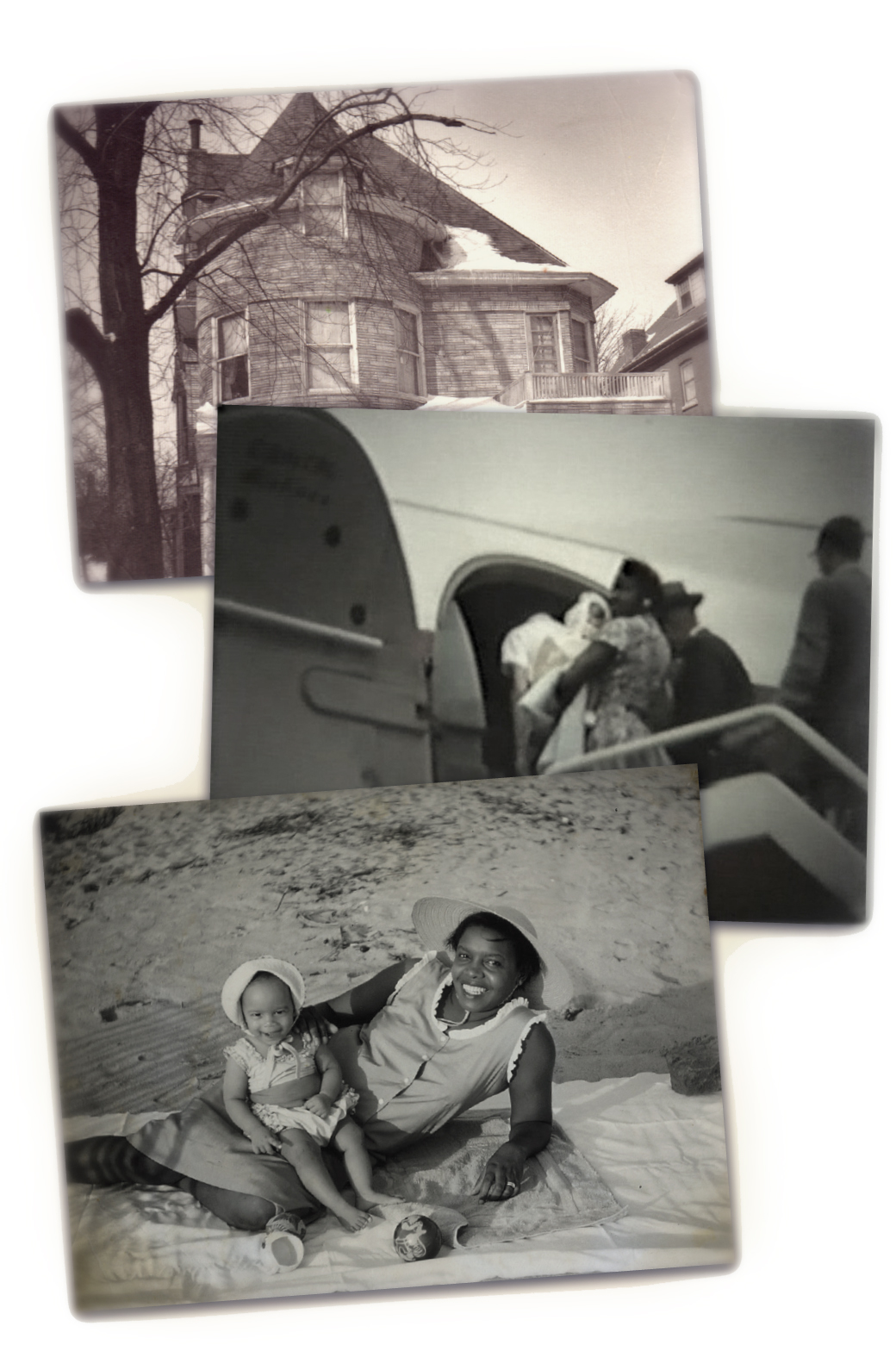

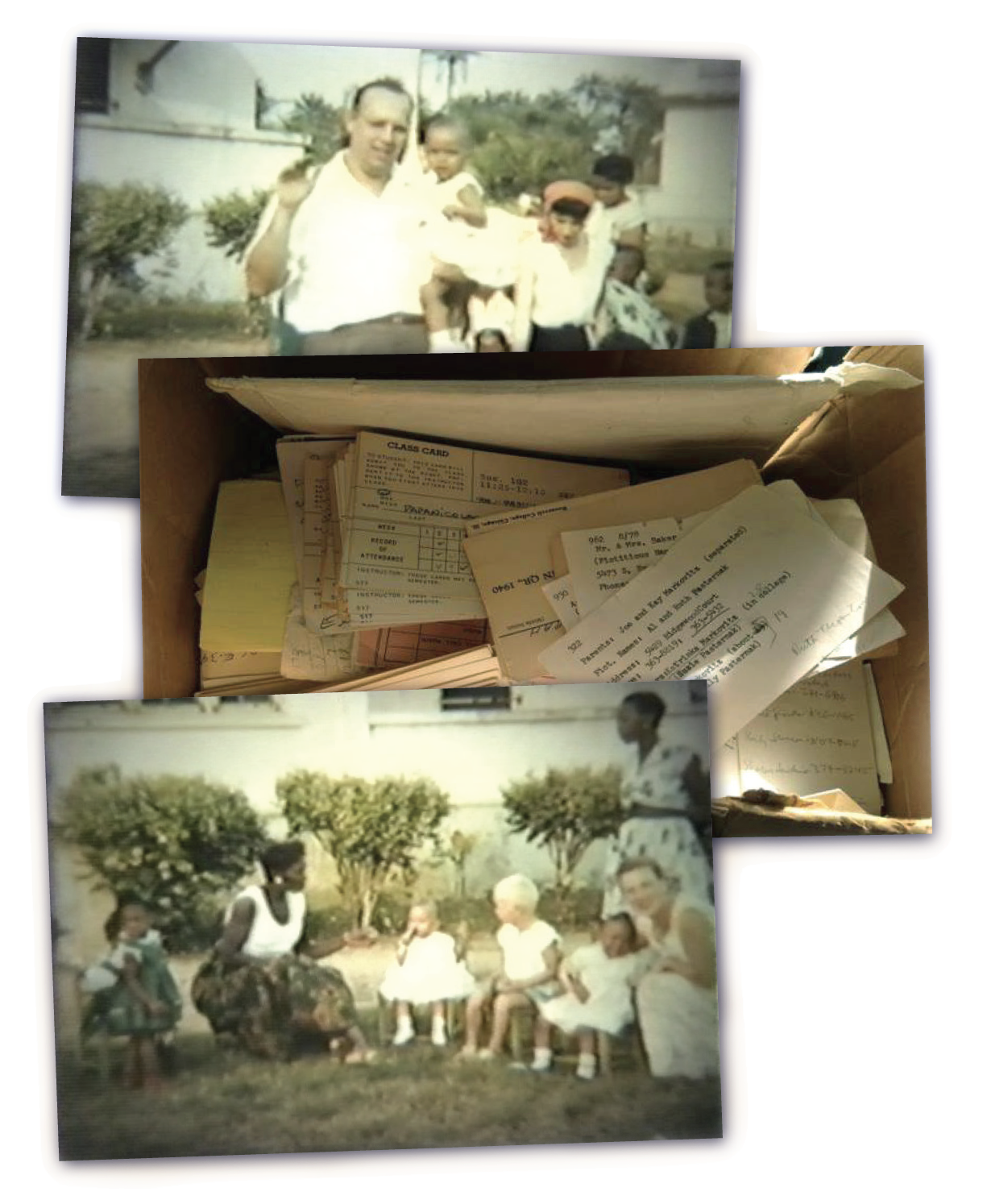

Roberts was no slouch when it came to adventure. When she was only three months old, her family moved to Liberia, where her mother had previously been an educator after first emigrating from Jamaica. After they returned to Chicago, it became their tradition to watch the 16mm family movies from their trip. In one clip, her father attends a trial in a remote village. The verdict: a heated knife to the leg. Whether or not the wound blistered would determine the defendant’s guilt. By the time Roberts was five, she had decided: Like her parents, she would pursue anthropology.

A FATHER'S LEGACY: PART 1

Roberts’ father was a “white boy” from an immigrant community in Chicago. His brother never forgave him for marrying a black woman. In 1937, when he was working on a master’s degree at the University of Chicago, he began what would become a lifelong undertaking of interviewing interracial couples. In his interviews he spoke with couples that had been married as far back as the late 1800s, the better part of a century before the final state bans on interracial marriage were struck down in 1967. The project ran like a thread through Dorothy Roberts’ formative years. The couples came to be involved in every aspect of family life: her babysitters, her piano teacher, the plumber, the carpenter, family friends. Her mother, who met Roberts’ father while working as a research assistant on the project, welcomed guests from all walks of life and parts of the world, exposing a young Roberts to invaluable diverse interactions. The interviews were to become a sprawling book. Several book deals and decades later, that book remains unwritten. It exists in 25 boxes of transcripts and papers piled high in Roberts’ office.

STUDENT OF THE WORLD

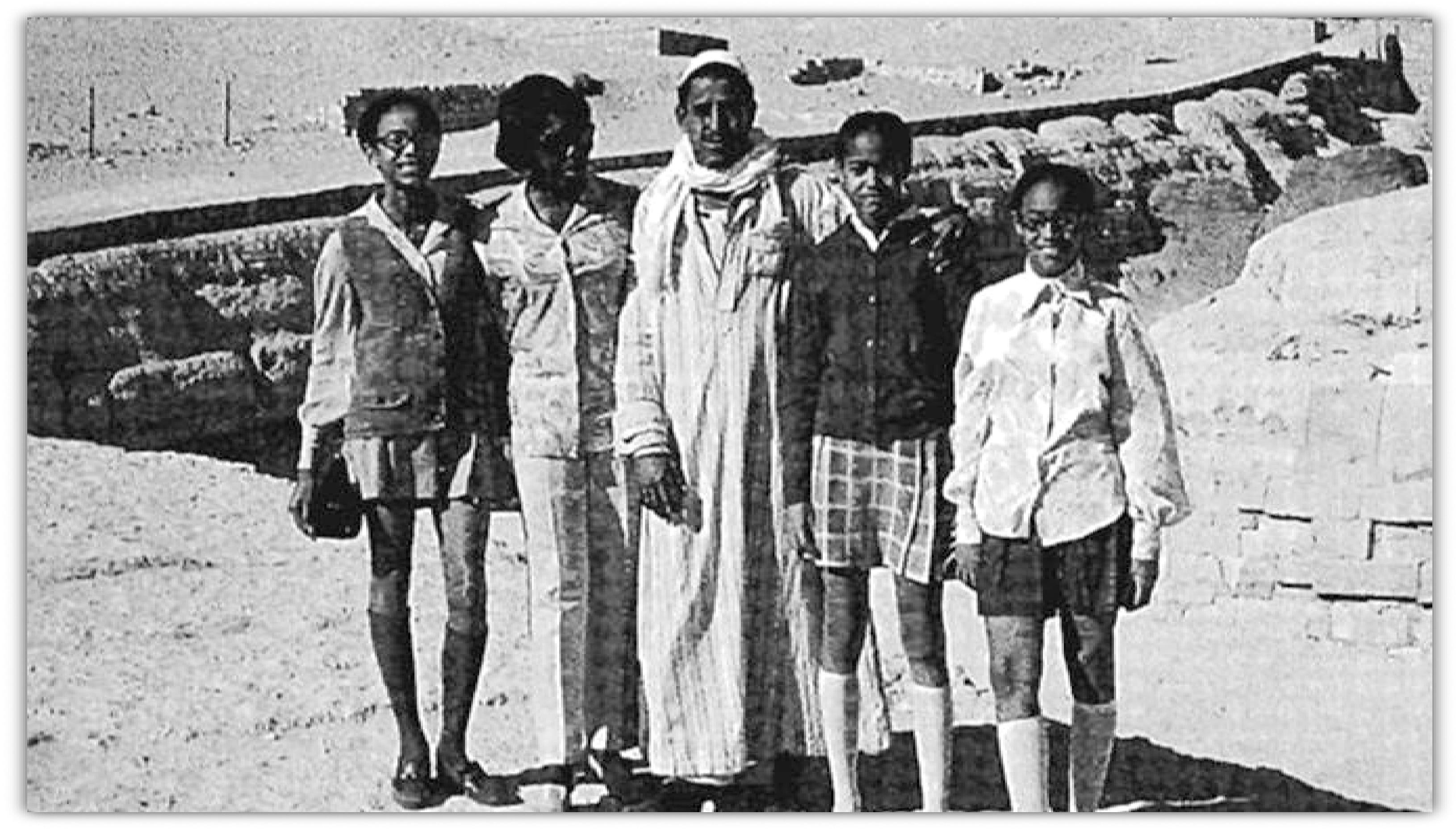

At their house in Maadi, a suburb of Cairo, Egypt, there was a beautiful garden Roberts’ mother tended. She hosted a constant stream of international students that introduced fresh ideas to the household. Roberts’ father had landed a Fulbright Fellowship to teach at the American University in Cairo. Roberts had just begun high school at a private institution that boasted a student body made up of the children of international diplomats and Texas oil executives, among others. Roberts’ best friend was Tunisian. They would learn to speak French, like many Egyptians, her French teacher told them, forbidding English in class. By the time Roberts returned to the States, her high school had to create special advanced French lessons for her.

HOME AWAY FROM HOME

Roberts’ dream to study anthropology had been secured. But after two years at Yale, she yearned for adventure. She spent her junior year at Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. Her host mother, Miriam, was a black-Colombian fortune teller who read cards and told Roberts she had a good soul. Miriam was from the remote region of Chocó, which had a population made up of the descendants of escaped slaves and indigenous people. Her husband was a white, elderly German engineer who worked for a gold mine there. Roberts could relate.

The trip to Chocó was inevitable. “The road disappeared long before you arrived,” Roberts recollects. “The bus jolted you mercilessly, so that the metal seats chafed the skin off your back.” Her hard-earned respite: a cot in a cinderblock house with rooms separated by sheets. She was awakened in the morning by a small boy yelling that someone had stolen his porridge. Mi avena! “There might not have been any running water,” she reflects, “but the people were welcoming and beautiful—I had never felt more at home.”

A PARADIGM SHIFT

There was trouble in paradise. Anthropology, Roberts’ first love, was not creating the kinds of opportunities she hungered for. “I didn’t have any mentors who could tell me how to use a Ph.D. to participate in social justice activism.” She made the decision to get a law degree and go straight to the heart of the policy debates. Soon, she was graduating from Harvard Law and learning litigation skills at a premiere Manhattan firm, but she had traded inaction for frustration. “Haggling over documents with opposing attorneys didn’t exactly allow me to delve deeply into social justice issues the way I wanted.” It became clear: She would follow in her parents’ footsteps; she would be an educator.

TUG-OF-WAR

While researching Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty at Rutgers University, Roberts became acutely aware of the disproportionate number of black children in the child welfare system, the result, she believed, of a fundamentally flawed approach based on applying punitive measures instead of supporting struggling families. Her second book, Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare, was the result. She was close to realizing her full potential as an interdisciplinary scholar and activist.

Roberts accepted a position at Northwestern, the same university where her mother pursued a Ph.D. in anthropology. “There is a photo of my mother shaking hands with the president of Liberia when he visited Northwestern,” she says. “I can’t imagine there were many black women—or many women at all—in Ph.D. programs in the 1950s. Knowing she was working on her doctorate when I was born was very inspiring to me when I was little.” Robert’s new position was a joint appointment as a professor at Northwestern’s law school and a faculty fellow at the Institute for Policy Research. Located on the university’s Evanston campus, the institute allowed Roberts to flex her formidable social science muscles. But she felt like she was being pulled between two worlds: law and the social sciences. Soon a new opportunity in Philadelphia would reveal itself. But was she ready to tear up her roots?

A HOME AT PENN

One campus. No racing across town. Penn seemed like a perfect fit. As a Penn Integrates Knowledge Professor she would have the opportunity to teach the diverse subjects she loved, not to mention join the newly launched Africana studies department. But how could she leave Chicago, the city that had nurtured her as a young girl with dreams of changing the world? “I remember Penn put us up at Rittenhouse Square during my first visit,” Roberts says. “The park was all lit up, and people were at the cafés at 11 p.m. There was a buzz, like Chicago. That was when I knew I could make this work.” With the launch of the Program on Race, Science, and Society, Roberts is looking ahead with the goal of changing the way we look at race forever. “We need to definitively reject the myth that human beings are naturally divided into races and instead affirm our shared humanity by working to end the social injustices preserved by the political system of race.”

A FATHER'S LEGACY: PART 2

The one-year-old birthday girl in the frilly tutu comes into focus, surrounded by black Liberian children and white Dutch neighbors. It’s one of many memories captured on 16mm, a reminder of a childhood defined by a mother and father’s commitment to education, love for travel, and belief in our common humanity. There are 25 boxes in Dorothy Roberts’ office waiting to tell a story. Of the triumphs and tribulations of hundreds of interracial couples over the better part of a century. Of the role of interracial marriage in the social upheavals that took place in that time. Of why a young white man in 1930s Chicago took it upon himself to conduct the interviews. Of what it means to be his daughter, reading them—and writing the book he never completed.

“I have to get it right,” Roberts says, with an almost visible weight on her shoulders. “It’s just too important a history to squander.” She was going through the boxes and found a stray envelope with notes scribbled down in longhand. If you look through her things you’ll find similar envelopes, with similar handwriting, in a similar voice. “I keep coming back to that book on yoga, and reading as a little girl about how we were all breathing wrong. It sounds strange but I think it helped me start to question authority, question the truths handed down to us."