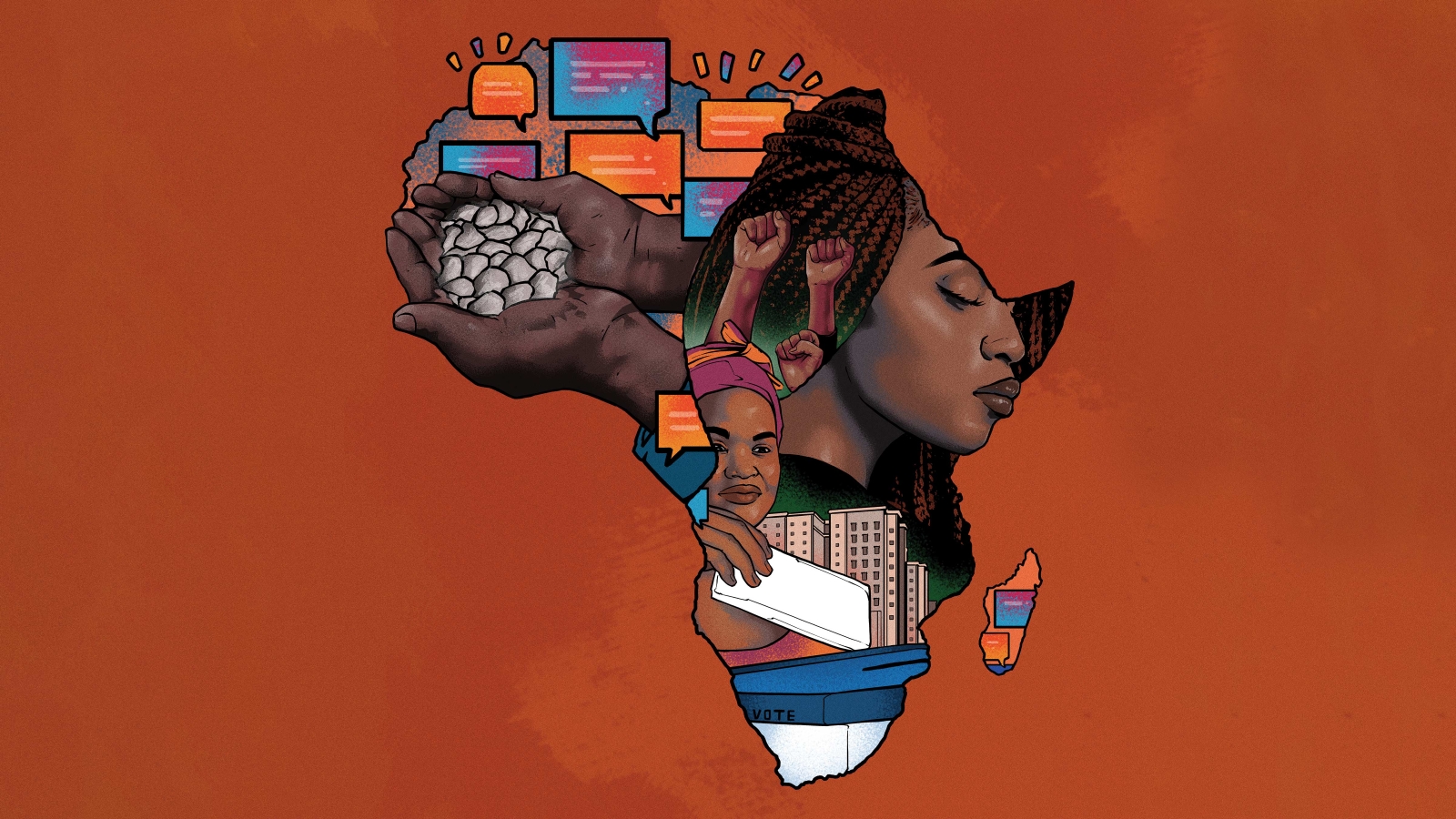

Omnia 101: Democracy in Africa

Wale Adebanwi, Presidential Penn Compact Professor of Africana Studies, discusses the state of democratic reform in Africa.

Omnia 101 offers readers a peek into what faculty do every day in their classrooms and how their research and expertise are inspiring the next generation.

Wale Adebanwi is the Presidential Penn Compact Professor of Africana Studies. His research and teaching focus on the social mobilization of power and interests in Africa. Adebanwi’s undergraduate course, Popular Culture and Youth in Africa, explores how popular culture offers escape and entertainment for young people while also working to transform African societies. We spoke with him about the successes and challenges of democratic reform in post-Cold War Africa.

Is democracy on the rise in Africa?

Yes and no. To the extent that democracy has become a norm, or a formal system of governance, in Africa, that is something to be celebrated. Because up to the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was a contestation about the premise of democratic governance as a way to rule society in Africa. The fact that many African countries have triumphed over that contestation by choosing democratic rule, plural, multiparty democracy, means that that matter was resolved in a significant way.

Wale Adebanwi, Presidential Penn Compact Professor of Africana Studies and Director, Center for Africana Studies

But this was merely a formalistic resolution. Most people accepted that the way to run African polities—and by polities, I mean states—was through democratic rule. Unfortunately, the forces that were arrayed against democratic rule did not give up. They did two things that I think are very interesting. The first was to become part of the democratic process. For example, military autocrats, one-party-state rulers, and anti-democratic forces joined the democratic process to seize power. They changed the means for accessing power, and because these forces became dominant in many democratic polities, it meant that some of the most vital institutions and processes that would otherwise deepen democracy were not, in fact, truly democratic institutions and processes.

The second thing was to sap democratic institutions of their dynamism and energy. For example, in many states, because of the legacy of military rule and one-party rule, antidemocratic forces ensured that the executive arm of government was overdeveloped in relation to the other two arms.

Some scholars have described what we have now as hybrid democracies, because there’s a large number of authoritarian institutions and leaders dominating many polities, and they constitute the core of the ruling elite. One of the implications is there is no guarantee that these states will continue to widen and deepen democratic rule and practices. There are serious structural problems that need to be resolved for democratic practice to become fully entrenched.

What are the challenges?

One problem is determining what kind of political architecture works best in states where different communities—ethnic, ethno-regional, religious, or a mix of the three—are living together. In many countries, this has been left unresolved since the end of colonial rule. Another challenge is the absence of a clear investment by the political elite in the mess, the true mess, of democratic politics. There is an eagerness to have things resolved quickly, which leads to sidestepping of democratic processes. In many of the African states, the executive tramples over the judicial and legislative arms of government because those in the executive arm do not have the patience for the complex work of democratic rule.

Yet, there is a lot to be said for the reality of democracy in Africa. With the new incidence of military rule—in West Africa particularly—the people are reminded that it’s better to maintain democracies—even if in name only—than to return to autocratic rule.

In which countries is the most progress being made?

It’s a complicated answer. Botswana is a good example of a country where democracy is thriving, despite some challenges in the last election. South Africa—institutionally, formally, and constitutionally speaking—is also a good example. The reality of it is far more troubling, but South Africa has perhaps the most robust and truly democratic constitution in the world. Its constitution not only recognizes democratic plurality, but it also honors plurality as much as possible, formally speaking, unlike other constitutions—including the American constitution, which was a paradox from its foundation. Unfortunately, South Africa seems to be going away from those foundational ideals, so, in terms of the practices, it is quite challenging.

Another paradox is Rwanda, a democracy in name that has to some extent an effective and bureaucratically rational government but is run by a democratically elected president who seems to be using elections as a way to perpetuate himself in power.

Western countries should do more to make it clear that they will not recognize any government that comes to power other than through free and fair elections.

What role does the legacy of colonialism play in the push for democratic reform?

As we know, most of these states are largely creations of colonial rule, with the exception of Ethiopia and to a limited extent, Liberia. So, the legacy of colonialism is central to how we understand the challenges. But my question is, how long can we use colonialism as the exclusive explanation for the crisis of the African state? I think that there have been occasions in African histories since the end of colonialism that showed clearly the capacity to triumph over this legacy. Unfortunately, some of those attempts at creating a viable democratic state have been subverted by internal elements as much as by external elements. For instance, we know that, until the end of the Cold War, Western nations, led by the United States, often subverted true democratic aspirations in Africa. But since the end of the Cold War, you can no longer make that excuse for many of these countries.

I think the greater responsibility lies with social forces within African states. There are sufficient organizational and agential materials to build coalitions that would ensure that these countries not only remain democratic, but also deepen participatory democracy. As things stand now, there are critical problems in most of these polities, but there are also emergent patterns that I think hold hope for the possibility of the democratic experiments to survive and even thrive.

Wale Adebanwi in conversation with Wole Soyinka, Nigerian playwright, poet, Nobel Laureate, and pro-democracy activist. Soyinka gave the annual Distinguished Lecture in African Studies at Penn on March 22, 2022. (Image: Eddy Marenco)

What role do economic pressures from other countries play in regard to democracy in Africa?

I think China, for example, will be a negative force in the long term. China’s main interests in Africa are the extraction of resources and the expansion of its global power. In the short term, it can be positive because there is a sense that good African leaders can exploit China’s interests to transform their economies, and not be used as merely instruments of Chinese interests. Unfortunately, I don’t see that in most of these countries. There is almost a reappropriation, so to speak, of the kind of relationship that existed between the West and many African countries and African leaders prior to the emergence of China. The difference now is that, unlike Western countries that paid lip service to democratic rule, human rights, and civil society in the Cold War era, China does not care about those things.

In many cases where you find development projects funded by China, these countries have few other options. China is there to provide loans and build infrastructure, which are urgently needed, but then China imposes a burden of debt, which I think it is leveraging in very methodical ways, and which I suspect many African leaders are not fully aware of—and it will come back to haunt them.

What can the United States and other democratic nations do to foster democracy on the African continent?

Since the end of the Cold War, the United Stateshas, to a large extent, allowed the organic development of democratic practice to thrive in Africa. Rolling back the interventionist attitude of the West has helped to ensure very robust associational life in post-Cold War-era Africa.

Social movements based in the West have also been supportive of this trend, unlike some states that speak powerfully to these ideals but never do anything concrete to support them. So, I think what is most needed is for the United States to support organizational movements that are dedicated to ensuring egalitarian polities and economic formations that support democratic systems.

The United Statesmust continue to show its willingness to support democratic rule, democratic associations, and free and fair elections. Western countries should do more to make it clear that they will not recognize any government that comes to power other than through free and fair elections. Unless it is made clear that global powers will not allow military rule to continue, there will be more military coups across the continent.

Do current events in Europe—Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—have an impact in Africa?

Russia is not a major player in Africa as much as the Western powers and China. Yet, a terrible signal is being sent to African countries when a country invades another for absolutely no reason. It’s also a challenge to America’s moral standing in the world. So, to that extent, it’s not in the interest of global peace, and it shouldn’t be allowed to stand. However, it must be noted that despite its limited influence in Africa since the end of the Cold War, Russia has been making efforts to expand its influence in Africa in recent times. Perhaps this is responsible for the decision of some African countries to abstain from the votes to condemn Russia’s action at the United Nations. Some suspected Russian mercenaries in the Wagner Group—a Russian paramilitary organization—have been involved in conflicts in Africa, including in the Central African Republic and Mali. Therefore, whatever happens at the end of the invasion could have impacts in some African countries.