From College Community to Career Path

Joyce Kim, an advanced doctoral student in sociology and education, wants to know what motivates undergraduates—especially those who are the first in their families to attend college—to choose the career trajectories that they do.

When PhD candidate Joyce Kim, C’15, arrived at Penn as a first-year undergraduate, she found the campus environment liberating. “Having primarily grown up in a homogeneous suburb of Dallas, it was a breath of fresh air to be in a racially diverse, not only campus, but also city,” she says.

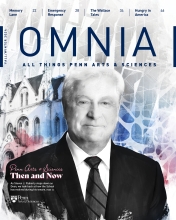

Joyce Kim

Other early impressions were the challenging academics, the intense pressures affecting her Penn classmates and friends, and the fact that so many graduating seniors chose careers in one of three highly lucrative fields: finance, tech, or consulting, “When I first got to Penn I wondered, ‘What in the world is consulting?’ I had no idea,” says Kim, who earned her bachelor’s in political science and, after completing a Fulbright and a master’s degree and working for a time, returned to Penn for a joint PhD in sociology and education.

“When we write our college admissions essays, we often talk about wanting to change the world, which suggests a whole array of career paths,” she says, “but I wondered how it is that students end up getting funneled into these very specific careers.” That question informs Kim’s current research, which examines the college-to-career transition, with a focus on how race and class affect students’ decision-making.

Finding Her Own Path

Kim’s own career path has taken many turns. After graduating from Penn, she won a Fulbright Research Fellowship and lived in Seoul, where she studied how North Korean defectors adapted to civic norms in South Korean society. That work was informed by family history; her father’s parents were refugees from North Korea.

After the Fulbright, Kim worked for an educational nonprofit called Year Up, a workforce development program for underserved young adults that provides skills training, internships, and community college credits. Her next stop was the University of Cambridge for a master’s in education under a Rotary Fellowship, where she briefly continued her work on North Korean defectors before ultimately deciding to return to the U.S. She also spent three years as a researcher at Harvard Business School, where she worked on projects related to how higher education can address intractable social problems.

When she first applied to Penn’s doctoral program, her plan was to study cross-racial student activism on college campuses—an interest that stemmed from her involvement with student minority coalitions when she was in college—but her earlier questions about career choices kept bubbling up. Ultimately, those questions set her on her current path. Her dissertation, which she is just beginning, will examine the different ways inequality can factor into the college-to-career transition.

Objections, Obligations, and “Selling Out”

As a first step for this work, Kim interviewed 62 students at a highly selective college she calls “Eastwood” (a pseudonym) about their career plans. About half the students in the study identified as first-generation and low-income (FGLI) and half as middle class. And, Kim says, because most research on FGLI students has focused on white, Black, and Latinx students, she intentionally sought out Asian students as part of the FGLI group. The study has been recognized with awards from the American Sociological Association and the Society for the Study of Social Problems, and a paper based on the research is forthcoming in the journal Social Problems.

While not all institutions define FGLI in the same way, Kim laid out specific criteria for identifying such students for her study, enrolling only those who were first in their immediate family to attend a four-year university and those whose families met the threshold to receive full financial aid. She acknowledges that some people view the designation as stigmatizing but says the students who participated in this project did not seem bothered by it, viewing it as a way to find community with one another.

Instead, the main theme that quickly emerged was the idea of “selling out.” “It came up repeatedly,” says Kim, “but the flavor and texture this idea took on varied by students’ racial and class backgrounds. Much existing literature focuses on individualistic job values such as finding a ‘good fit,’ pursuing a passion, or work-life balance. I did find evidence for that, but I also found a moral component that was colored by students’ class and racial backgrounds in ways that previous research hadn’t explored.”

She identified, for instance, what she calls “objections based on a value of social good,” such as the desire to avoid working for companies perceived as responsible for some kind of social harm. But she says it was primarily those in her study who identified as Asian and Black FGLI students whose interview responses cited these objections.

For some FGLI students, however, financial considerations took precedence, pitting their social objections against a sense of obligation to family or to their ethnic or racial community. “I found that the Asian and Black students more often cited these familial and ethno-racial obligations as part of why they wanted to pursue certain careers,” Kim says.

“I think the tension that comes with students grappling with the moral aspects of what they want to do and who they want to be is really important.”

She recalls one young woman who went to work for a large online retailer because the job helped her pay her family’s rent, despite her negative feelings about the company. “I remember she kept sighing during our interview,” says Kim. “I think the tension that comes with students grappling with the moral aspects of what they want to do and who they want to be is really important.” Students also reported as points of tension the ratcheting up of on-campus recruitment and competition over club memberships. Club memberships are the topic of a study Kim is working on this summer with Tristan Ly, C’24, a sociology major who graduated in May.

“The Eastwood interviews pointed not only to how students grappled with the moral dimension of their career decisions, but also how at elite private institutions, clubs can impede or facilitate access to resources for the most lucrative, high-paying jobs in finance, consulting, and tech,” she says.

Helping Students Think Critically

Kim’s dissertation fieldwork, beginning this fall, will expand on the Eastwood and club studies to look more deeply into various mechanisms of inequality in the college-to-labor market transition and how they differ by students’ backgrounds—particularly race, class, and gender—and institutional setting. She’ll conduct interviews at one private, highly selective institution and one public, broad-access institution.

“It’s a big umbrella,” she says. “I’ll be looking at what factors either facilitate or impede upward mobility in the college-to-career transition.”

Kim says she hopes her research will have tangible applications. She would like campus staff, faculty, and administrators to be more cognizant of considerations beyond “finding a passion,” such as family needs and other motivations, when advising students. She also hopes that her research can encourage policymakers to take a holistic approach in national conversations about the college-to-career transition.

One of her most formative undergrad experiences was working with the Netter Center, which was a strong draw for her to come back to Penn. She is currently a Provost’s Graduate Academic Engagement Fellow at the Center, and some of the insights from her research will eventually be translated into an Academically Based Community Service class to address the civic purposes of higher education.

As for her own future work aspirations, Kim is looking at the broader picture.

“I’d like to have a career where, through my research and teaching, I can help students and members of the academic community focus on encouraging students to think critically about the purposes of higher education and what it means to them, not only for their careers, but also ultimately as citizens,” she says. “That’s very important to me.”