Bringing it All Together

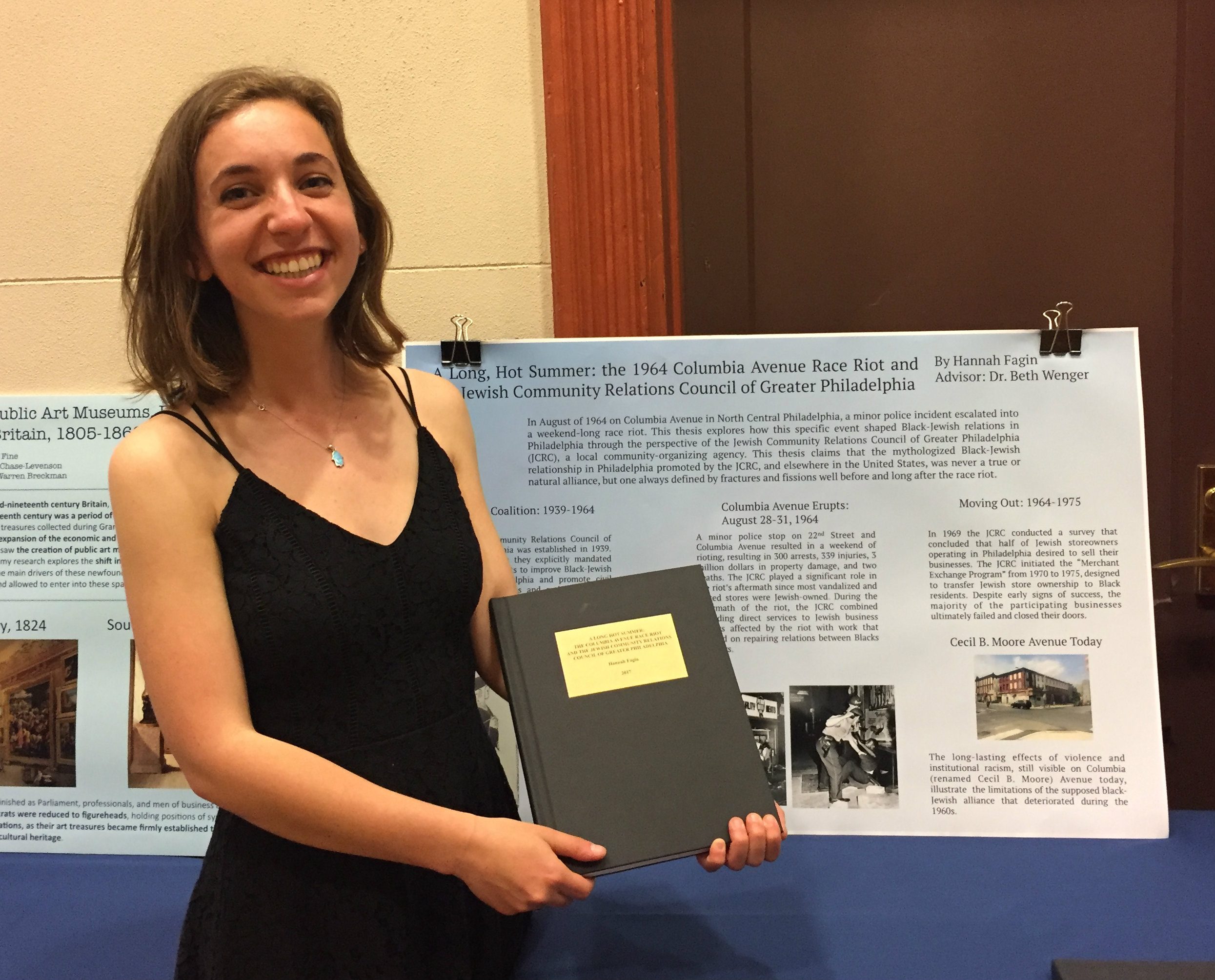

History major Hannah Fagin, C’17, sheds new light on Philadelphia’s Columbia Avenue Race Riot.

“It was like putting together the pieces of a puzzle.” That’s how history major Hannah Fagin, C’17, describes researching, organizing, and writing her senior Honors thesis, A Long, Hot Summer: The 1964 Columbia Avenue Race Riot and the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Philadelphia. Recently awarded the History Department’s Thomas C. Cochran Prize for the best Honors thesis in American history, her richly detailed work offers new insight into the complicated relationship between Blacks and Jews in Civil Rights-era Philadelphia. It also gave Fagin the opportunity to draw on a range of existing academic and personal interests and to open the door to new ones. Here, we speak to Hannah about the many pieces that came together in her thesis project.

How did you discover your thesis topic?

I knew I wanted to explore Black/Jewish relations in the context of the Civil Rights Movement. My thesis advisor, Beth Wenger [Professor and Chair of the Department of History] suggested that I visit the Urban Archives at Temple University and look at its collection of documents from the Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC) of Greater Philadelphia, a local Jewish group founded in 1939 and committed to reaching across religious and racial divides. As I went through its papers, newspaper clippings, and photos, I began to see that the organization was increasingly focused on North Philadelphia and the growing tensions between Blacks and Jews who lived and worked there in the 1950s. When I read about the Columbia Avenue Race Riot that broke out in August of 1964, I knew I had found a pivotal moment in this story and one I could focus on.

Can you give an overview of the riot?

In August 1964, two Philadelphia police officers confronted a Black couple in their car at the corner of 22nd Street and Columbia Avenue, now known as Cecil B. Moore Avenue. This was a neighborhood that was once heavily Jewish, but by 1960 was predominantly African American, though Jews continued to operate businesses there. What started as a minor traffic dispute quickly escalated into three days of protest and destruction as residents looted local shops. Almost all white-owned businesses in the neighborhood, most held by Jews, were destroyed.

How does the Columbia Avenue Riot fit into broader Civil Rights-era history?

It was one of many riots that occurred in U.S. cities during the mid- to late 1960s. As in other cities, among the root causes were persistent racial inequality, joblessness, and poor housing. But unlike other cities, the Columbia Avenue Riot produced comparatively less physical injury and property damage. As a result, it hasn’t been studied as much as the other riots of the period, and it hasn’t been examined in-depth from a Jewish perspective. Those who have looked at it talk about the riot as an abrupt collapse of the storied alliance between Jews and Blacks forged at the outset of the Civil Rights Movement. In my paper I argue that the riot should be reframed as a culmination of tensions long-present in the Black/Jewish relationship.

Among those you thank at the beginning of your thesis are your grandmother and cousin. What role did they play in your project?

One of the things we learned in our thesis seminar was to begin with a personal connection to your subject. My family is from Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn. They owned a hardware store from the 1940s to the late 1970s and were there for the 1964 Bedford-Stuyvesant riot. Their experience parallels much of what I saw in my research. When you’re in the archives, sifting through so much detailed, often irrelevant, information, it’s hard to stay focused; that personal connection helps you to stay on track and have faith that things will fit together.

How does your thesis connect to your course work?

In my sophomore year, I took America in the 1960s, which gave me a context for what was happening in the country and the world at that time, as well as a strong interest in the period. The final paper for the class required us to do an oral history, and I interviewed a family member. In addition to learning how to take an oral history, I learned how to integrate memories with primary and secondary sources. For my thesis, I conducted several oral histories.

What resources helped you through the thesis process?

The History Department’s thesis seminar brings together all history students writing a thesis. It honed our research skills, and once we began writing, we reviewed each other’s work weekly. Professor Wenger, my advisor and seminar leader, was very hands-on in terms of research, writing, and editing. When you are doing original research, one of the biggest challenges is how to organize all of your information into a bigger picture, and she was enormously helpful with that. Writing my second chapter was really difficult. I was trying to put together a chronology of the riot and make my argument at the same time, and it wasn’t working. Professor Wenger helped me to distinguish and separate those two strands, and she pushed me to rewrite and rewrite. It’s now, in my mind, my strongest chapter. In terms of financial support, the Department of History and CURF were great. Most of us used the summer after junior year to do our research and they provided the funding to make that happen.

In addition to your history major, you also were a double minor in art history and French and have held internships at organizations such as the National Museum of American Jewish History, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and, this summer, at the Public Art Fund in New York City. Do all of these interests complement each other?

This fall, I’m starting my Master’s degree in art history at University College London, and that brings together many of my academic interests. Issues I touched on in my thesis intersect with so much that continues to interest me. Right now, for example, I’m thinking about public art and how we all experience art differently. There are strong parallels to my thesis research, which showed me that in cities people can share the same space but have very different experiences within it.