Bringing History to the Surface

Mantha Zarmakoupi, Morris Russell and Josephine Chidsey Williams Assistant Professor in Roman Architecture, conducts underwater surveys to map ancient travel and political intrigue.

For Mantha Zarmakoupi, an archaeological survey isn't just about the artifacts—it's about reliving the human experience.

“We were cleaning debris from a building that had fallen off a cliff on the island of Kythnos, and I saw this piece of clay with the imprint of a finger,” says Zarmakoupi, the Morris Russell and Josephine Chidsey Williams Assistant Professor in Roman Architecture in the Department of History of Art. “It was actually a seal from the Hellenistic period and on the other side was the representation of somebody in profile. But I remember the human touch of this object, the memory of the person who probably put the clay in that mold, rather than what we value in archeology—the seal.”

Zarmakoupi’s research focuses on the broader social, economic, and cultural conditions underpinning the production of ancient art, architecture, and urbanism, and the ways in which the cultural interaction between Greeks and Romans informed their artistic production and built environment. Her publications include Designing for Luxury on the Bay of Naples (c. 100 BCE – 79 CE): Villas and Landscapes and “Balancing Acts Between Ancient and Modern Cities.” She co-leads the Delos Network, a collaborative project that investigates the history and legacy of the Delos symposia, which were organized in the context of 1960s and 1970s discussions about the future of urban planning.

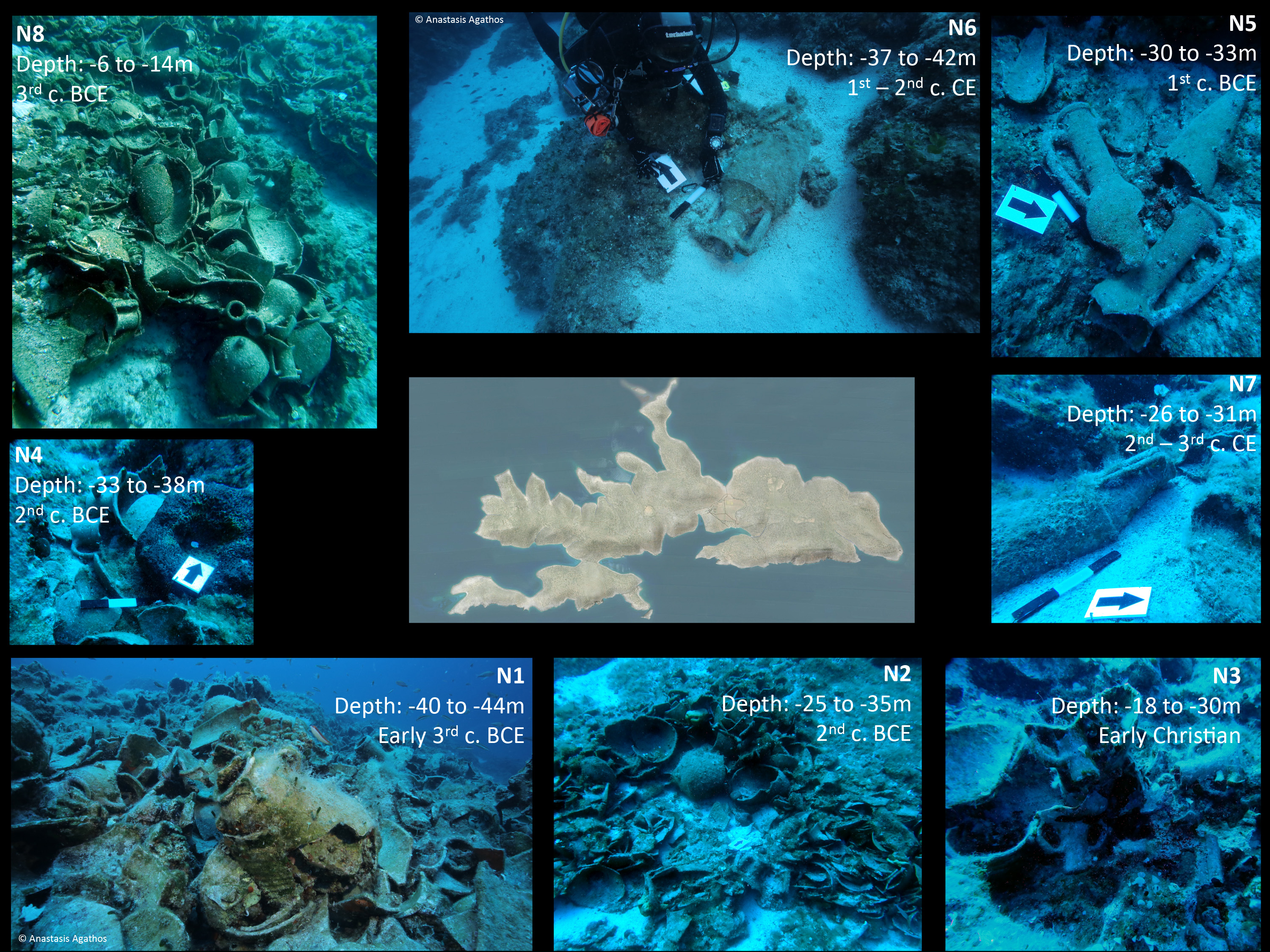

Zarmakoupi's investigative work isn't limited to land. She first initiated the underwater survey around Delos (2014-), which was the home of the sanctuary of Apollo since the archaic period and became an important trading point in the late Hellenistic period. An accomplished diver, her newest project sees her venturing into the depths off the shores of small Greek islands whose mysterious histories could reveal the intricacies of ancient Greek maritime networks and political intrigue. Working alongside her co-director George Koutsouflakis, who is Head of the Department of Underwater Archaeological Sites, Monuments and Research in the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities in the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports in Greece, Zarmakoupi started surveying Mediterranean shipwrecks around the islands of Levitha, Kinaros, and Maura in 2019.

“These are stepping points that led to the connection between Asia Minor and Greece,” Zarmakoupi says. “But an island like Levitha is completely unknown in the sources except as a marker for navigation. Nobody has investigated it because there is not a village or anything there.”

Levitha, located in the east of the Aegean Sea, isn’t completely uninhabited. For over 150 years, a family has farmed and tended goats, and runs a small taverna restaurant, which, for the surveyors, became a place for respite and discussion of findings, among the researchers and with the family. Developing this relationship was crucial to both their research—the family was the team's first stop for anecdotal evidence of shipwrecks—and to build trust.

“The people that live on the islands are afraid that if the archeologists come they will take this land away from them,” Zarmakoupi says. “They want the history to have some attention, but they are a bit suspicious of any authority coming on the island. That's the micropolitics of archeology.”

The survey dive team was comprised of people from the Ephoria, the institution that supervises underwater archeological work in Greece; students from the University of Athens; and William Pedrick, GR’19. Underwater surveying is especially time-consuming and taxing, requiring both detailed planning and equipment preparation. There are also potential health complications from being at depth. Zarmakoupi suffered an ear infection which followed her for a month and a half.

“It's generally better to avoid putting yourself at the limit because being in the water is very tiring,” she says. “In underwater archeology, you have to do everything to make sure that your one hour in the water is well spent.”

Zarmakoupi says another crucial factor with underwater surveying is the buddy system. “Because the thing with the water is, you're very confined and your reactions are slowed down, so it forces you to be dependent on others.”

Zarmakoupi’s team’s first lead came from George Koumbas who had done a leisurely dive. The team also depends on local knowledge. The Kamposos family, who live on the island, helped to map out each of the harbors around Levitha. The team then began navigating the coastline at a depth of 10 to 40 meters.

Knowing common pitfalls about the ancient sailing routes helps to provide context for the surveys. “Usually it's the South wind that is difficult for sailors,” Zarmakoupi says. “They want to avoid the North wind, which is the most relentless, but in an effort to do that, they get caught in other local currents and they cannot control the ship.”

“I believe this is a part of our mission in archeology. The more you speak about the finds and communicate why they're important to the community, the more they are informed.”

In Levitha, the team ended up charting a series of shipwrecks that date from the Hellenistic to the Byzantine period. Zarmakoupi says that the shipwrecks they discovered, coupled with acropolis and watchtower ruins found on the island, suggest competing powers in the Aegean in the Hellenistic period. This fits with historical sources that cite similar narratives regarding other nearby islands, like Delos.

“After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, Hellenistic monarchies that rose were competing with one another for power,” Zarmakoupi says. “Delos is a case in point, where there was a competitive display between these monarchs. And so, the fact that we have this fortification found on Levitha in the Hellenistic period fits well within the narrative of the political dynamics of the period.”

The team brought up a number of amphorae—a type of container—from each site, to clean and draw and then date. To the family that had fed them each day and lent them local lore, the survey team temporarily left a larger-than-life relic: an ancient anchor stock. The family will safeguard it before transporting it to Athens.

“I believe this is a part of our mission in archeology,” Zarmakoupi says. “The more you speak about the finds and communicate why they're important to the community, the more they are informed. This creates less tension and avoids opportunistic excavations.”

The survey project has two years remaining, with plans for the team to return to the islands sometime in 2021.