Beyond the Policy Paper

PDRI-DevLab, only two years old, is on the ground in developing nations to generate better evidence that can influence real-world decisions.

(Image courtesy of Heather Huntington)

Two years ago, during one of Guy Grossman’s frequent trips to Uganda, he had some downtime between his lectures for the Penn Global class he was there teaching. So, he arranged a meeting with the top official in the Ugandan office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). During that meeting, Grossman posed a question: What keeps you up at night?

At the time, budget tightening in Uganda, which hosts more refugees than any other country in Africa, had cut support for 85 percent of those refugees, though the 15 percent of neediest refugee households would still receive the same level of provisions. UNHCR was worried about the implications of the aid cuts for this marginalized population but wasn’t sure how to assess the impact of this dramatic policy shift. Grossman had an idea: The Penn Development Research Initiative (PDRI), which he’d created in 2020 to address the challenges facing developing nations, could survey households just above and just below the 15 percent need threshold. His team would collect data for a year to show the effect of the aid cuts on refugee well-being.

The project had potential because Grossman, David M. Knott Professor of Global Politics and International Relations, had relationships in Uganda and the backing of Penn’s resources. The proposed study had a robust design, and because it would happen in partnership with UNHCR and the Ugandan prime minister’s office, it would have funding and access to the refugee population. Grossman could recruit Penn undergrads to help undertake the in-country research.

Most importantly, Grossman says, “it was going to generate hard evidence.”

The study would also potentially provide UNHCR a useful tool, says Erik Wibbels, Presidential Penn Compact Professor of Political Science and founder of DevLab@Penn, which assists social scientists at the University with research designs. “They could take it to international audiences and say, ‘Listen, you don’t give us the money that you say you will every year, and the result is that there are refugee kids in Uganda who are starving.’”

We’re in the room with the policy people and they will change their programming based on what’s being studied. That’s pretty powerful.

It was just the kind of project Grossman and Wibbels envisioned for PDRI-DevLab. The initiative, which brings together dozens of Penn faculty and students from across seven schools, focuses on three flagship themes—migration and forced displacement, environmental and land policies, and big-data analytics—and has projects in 27 countries so far.

It’s more than publishing ideas in policy papers. It is a quest to investigate social, political, and economic issues seen in developing countries and to find actionable data for policymakers.

A shared goal across different disciplines has taken the group on unexpected paths. Wibbels created Machine Learning for Peace, a big-data initiative to improve the timeliness of actionable data on developing countries’ day-to-day politics and to forecast democratic backsliding, conflict, or other potential crises. Then, through PDRI-DevLab, he met Irina Marinov, an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Science who studies oceans.

“I don’t know the world where Irina and I would have come up with something” to collaborate on, Wibbels says. “But because of this attempt to build bridges across disciplines, we started thinking.”

It is not difficult to find rainfall levels for the past week from anywhere across the world, but Wibbels knows policymakers don’t care about the measured rainfall; they want evidence to understand the human implications. “We know when catastrophes happen,” Wibbels says, “but we have very little data at the level of villages in northern Nigeria that are facing climate change, which is bringing herder communities into their villages and causing all sorts of conflict. That’s the beginning of something really big.”

Wibbels wrote a proposal with Marinov to create something that would generate better data. They won a $1.6 million grant in August 2024 from the U.S. Department of Defense’s Minerva Research Initiative. “I don’t know anything about climate science,” Wibbels says. But Marinov does—and that’s the beauty and promise of PDRI-DevLab. At its core, it is trying to institutionalize the quest for better data that can then inform policymakers. It is why Grossman could ask a Ugandan official a straightforward question two years ago. He knew he could propose a solution to whatever complicated answer followed.

“OK,” Grossman said that day, “let’s find the evidence.”

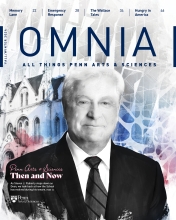

Grossman took a shorter trip to North Carolina four years ago. He wanted to meet Wibbels, who, along with Heather Huntington, an associate professor of practice in political science, had started DevLab at Duke. There was no hub for this type of research at Penn. Other universities are better known for their work in developing countries, but Grossman wanted something more than a lab and something smaller than a large-scale center. Something that would not grow stale over time, a way for Penn to leverage its strengths.

By 2022, Grossman had helped recruit Wibbels and Huntington to Penn. They created PDRI-DevLab.

“To be able to push for high-quality, impactful work within your institution, you need to bring people together, right?” Grossman says. “You need to create an intellectual community, and that intellectual community should span more than one discipline. If you think about some of the big challenges of our time—cross-border migration, climate change, and democratic erosion—it’s rare that one perspective can capture them in totality. You might need someone who knows more about society and more about economics and more about how political systems work.”

All of them are working on a multifaceted problem. There’s a migration part, an agriculture part, a climate part, a human trafficking part. All of this comes together in a way that exemplifies what we’re trying to do.

Until recently, PDRI-DevLab had just one full-time employee. It has grown enough to hire two research managers, an administrative assistant, three data scientists, several PhD-level researchers, and a small army of undergraduate fellows. Huntington, PDRI-DevLab’s executive director, has a background in policy. Those connections have helped the initiative secure a strong donor base and are part of her pitch to faculty and students thinking about collaboration.

“We’re in the room with the policy people,” Huntington says, “and they will change their programming based on what’s being studied. That’s pretty powerful.”

Huntington had a project in Zambia to promote organic quinoa growing among subsistence farmers. But when she and fellow researchers went into the field, they realized farmers would be required to cut down trees to qualify for an organic farming program. They flagged it with the policymakers and implementation partners, and the project shifted to agricultural interventions that would not motivate extensive land clearing.

For his part, in addition to work in Uganda, Grossman is heading a $7.9 million project with the nonprofit Winrock International to study the relationship between climate change and human trafficking vulnerabilities. The research team, whose main objective is to analyze the effects of better agricultural practices for Bangladeshi farmers, includes an international relations PhD student who specializes in gender issues, a postdoc with expertise in public policy, and a behavioral economist from Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine.

The point is to build a bigger engine to change the way the policy world works so that lives on the ground can improve and policy dollars are spent more intelligently. And to really do that at scale, we need a lot of people.

“All of them are working on a multifaceted problem,” Grossman says. “There’s a migration part, an agriculture part, a climate part, a human trafficking part. All of this comes together in a way that exemplifies what we’re trying to do.” The project is supported by the U.S. State Department, the field’s biggest funder. Grossman and his team have periodic calls with those officials to explain their methodology and provide updates on the project’s progress.

It’s a fundamental shift in the way research gets conducted to help millions across the world in need, Wibbels says. “Those efforts have historically been very poorly informed by evidence. We need better evidence to improve policy. To improve real human outcomes. And there’s been a growing taste in the policy world for improving the quality of evidence.”

The point, he adds, is to “build a bigger engine to change the way the policy world works so that lives on the ground can improve and policy dollars are spent more intelligently. And to really do that at scale, we need a lot of people. Guy and I and 10 others like us can’t do it alone, so that’s where education comes in.”

PDRI-DevLab has postdoctoral fellows and an expanding internship program that included 22 full-time undergraduate fellows this past summer. The team reimagined an undergraduate minor in international development to make it much more data-centric. In fall 2023, PDRI-DevLab launched a fellowship program that offered a semester-in-residence for social scientists from sub-Saharan Africa.

There’s also a pre-doctoral fellow program that brings students from low- and middle-income countries to Penn, the aim of which is to make participants more competitive in gaining admission to PhD programs. One student who came from the West African country of Benin was recently offered a spot at a social science PhD program at Princeton, the first Beninese person to accomplish such a feat there. PDRI-DevLab has also recruited students from Turkey, Malawi, Morocco, and elsewhere.

“With the help of the School of Arts & Sciences,” Grossman says, “we created something that didn’t exist.”

Two years in, PDRI-DevLab is making real headway. And it will continue to work toward gaining an audience with foreign policymakers, wielding data-driven ideas that meet them where they are, responding to real-world questions and creating new partnerships along the way. “It makes you feel good,” Huntington says, “that the work you’re doing is informing these sorts of activities.”