When David Grazian began to make weekend visits to the Philadelphia Zoo with his young son, he didn’t imagine that he would one day find himself on the other side of the exhibits mucking out cages, presenting boa constrictors and lizards to zoo visitors, and preparing meals of beef soaked in cow’s blood for wildcats.

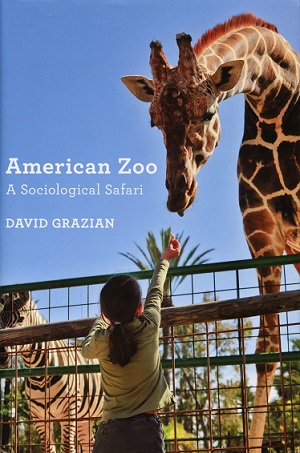

But Grazian, an associate professor of sociology, became fascinated by the cultural world of the American zoo. And so the social scientist traded in his professorial tweed for khakis and work boots and spent four years as a zoo volunteer. The result is his recently published book American Zoo: A Sociological Safari.

According to Grazian, the boundary between nature and human civilization is an artificial one, and nowhere is this idea more starkly illustrated than at the zoo. He writes, “With its carefully curated animal collections, audiovisual entertainment media, educational and conservation programming, and staged encounters with wildlife, the zoo provides a fitting model for how humans distill the chaos of the outdoors into legible representations of collective meaning and sentiment that project our prejudices and desires, past and present.”

Grazian’s fieldwork took him to 26 zoos, aquariums, and marine-mammal parks across the country to study animals and exhibits; the zoo-going public; and the communities of zookeepers, educators, designers, marketers, and volunteers who make the contemporary zoo experience possible.

Today’s zoos have moved away from the stark animal cages of the past and have embraced naturalistic models of presentation that mimic animal habitats, yet the book explores the many ways in which they present a highly mediated view of nature. Most obviously, major zoos have invested heavily in special attractions like interactive tours, 3-D movies, animal rides, birthday parties, Easter egg hunts, and hot-air balloons.

But since their beginnings in the 19th century, American zoos have also carried the mantle of conservation, both through long-established captive-breeding programs for endangered species and, more recently, through field-based conservation efforts. It is in this area, Grazian argues, that zoos can and should play a vital role in educating people about threats to both animal life and human societies, especially global warming.

“Doing the research for this book helped open my eyes to a wide range of environmental issues that sociologists have been slow to study,” says Grazian, whose current research focuses on the cultural consequences of climate change. “I’m interested in how we as humans experience and invest meaning in changes that have already begun to occur as a result of human-induced global warming.”

Grazian proposes three crucial roles that zoos can play: They should continue to function as animal sanctuaries, though he argues for a scaled-down form that concentrates resources on a smaller number of species using the highest standards of care. He also urges zoos to take the lead in educating the public about climate change by functioning as schools of environmental education. Finally, Grazian argues, zoos can be urban showcases for green infrastructure such as sustainable energy systems, green roofs, and water recycling systems—infrastructure that he says cities will need to adopt to survive in a warming world.

“Zoos attract people from all walks of life,” says Grazian, “and so in a way zoos offer us perhaps an ideal place for communicating with the largest possible mass audience about the dangers of the current environmental crisis, the importance of biodiversity, and the threats to the continued existence of life on earth.”