Countering the Assumption of the ‘Intact Mind’

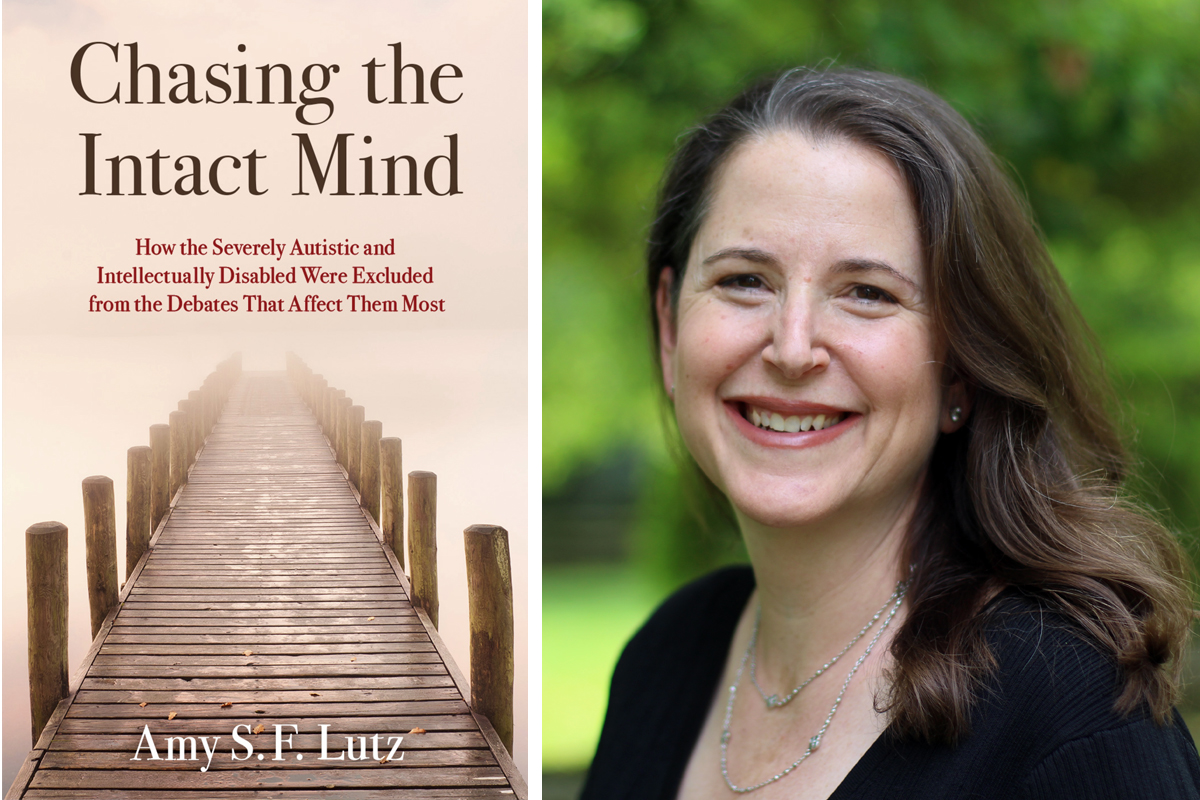

Amy Lutz, a senior lecturer in History and Sociology of Science, discusses her new book about autism, intellectual disability, and her beliefs about the need to provide services for the most severely impaired.

Amy Lutz found the corner of academia she currently inhabits late in life. “My first graduate degrees were in English literature and fiction writing,” says Lutz, now a senior lecturer in the Department of History and Sociology of Science.

When her oldest child Jonah was diagnosed with autism as a young boy, however, Lutz shifted her focus away from fiction and toward learning what she could about severe autism. “I decided to go back to school because I was really curious how we got to this place. It’s a fractured community,” she says. “The major fault line is primarily between parents of those who are severely autistic on one side and on the other, people who are much more mildly neurodiverse and can advocate for themselves.”

In 2020, Lutz published We Walk: Life with Severe Autism, a series of essays about subjects like religion, use of medications, and family life through what she describes as the “lens of severe autism.” Her third book, Chasing the Intact Mind: How the Severely Autistic and Intellectually Disabled Were Excluded from the Debates that Affect Them Most, comes out in October.

OMNIA spoke with Lutz about her latest work and what she hopes it will accomplish.

You have an intensely personal connection to this work. Can you start by telling us a little about Jonah?

He is 24 years old. He has some language but no abstract concepts. He’s significantly intellectually disabled, epileptic, and has a history of dangerous behaviors, including aggression, self-injury, and elopement. He’s going to require around-the-clock supervision for the rest of his life. There’s a not-insignificant population like my son who can’t self-advocate because their cognitive impairments preclude that—researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently reported that almost 30% of autistic children fit this profile.

There is this rosy narrative about disability, specifically about autism, because autism in the public sphere has come to be associated more with the quirky genius than with the kind of severe impairments that restrict opportunities. So, the purpose of my work is to shine a light on that end of the spectrum and to make sure it’s central in disability service provision. If we design supports based exclusively on the articulated needs of neurodiversity advocates, we really fail the actual consumers of those services, who are, on the whole, more severely impaired.

Your new book is called Chasing the Intact Mind. What do you mean by “the intact mind”?

It’s the idea that inside someone who looks severely autistic is a genius intellect just waiting to be accessed. This idea is very common in autism discourse, and it’s pretty unique to autism; you don’t hear this assumption in conversations about other intellectual disabilities. You can find it in the very first autism parent memoir, The Siege by Clara Claiborne Park, which was published in 1967. In it, she writes of trying to break down the walls of autism to reach her daughter.

How was autism viewed at the time of Park’s book, and how has it changed?

Autism was originally considered a psychiatric disorder very similar to, or even indistinguishable from, childhood schizophrenia. Psychoanalysts believed that it was caused by bad mothering and could be reversed with proper psychiatric care. Then in the 1970s and ’80s, medical thinking around autism really changed; researchers abandoned psychoanalysis and adopted a much more biological approach to autism, seeing it as something people were born with, something for which there was no cure.

You would think that parents would feel acquitted—the doctors were now on their side. But this biological model of autism foreclosed the possibility of the intact mind, and so was rejected by many parents in the memoirs published even after that shift. And I totally understand the need to preserve that hope of recovering the intact mind—so much of what we consider the good life is predicated on “typical” intelligence: college, a meaningful career, reciprocal and intimate relationships. Jonah will never have any of these, and it took me a long time to come to terms with that.

In the book’s second half, you offer three case studies to highlight how you believe this “intact mind” assumption undergirds policy and practice today. Can you talk us through them?

The first is about the increasingly successful fight to eliminate 14(c) vocational programs, traditionally known as sheltered workshops. These are authorized by the Department of Labor to pay a subminimum wage to some disabled people based on their productivity. These programs have been under attack for a long time and many states have phased them out because there’s this thought that if people weren’t stuck in the sheltered workshops, they could work competitive, minimum-wage jobs. But the reverse is actually true, and the program is extraordinarily popular with participants and their families.

The second case study is about the erosion of guardianship as a model of decision-making. This is largely driven by the United Nations, which simply declared in the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities that all people could make their own decisions, even though people like my son or patients with dementia or traumatic brain injuries obviously require this legal supervision to keep them safe.

The final case study is about the resurgence of facilitated communication (FC), which is a kind of intervention in which a non-disabled facilitator helps a disabled user communicate or spell out messages on a keyboard or letterboard. Dozens of controlled studies have shown overwhelmingly that the output of FC is unconsciously controlled by the facilitator, not the user, similar to a Ouija board. You’d think, okay, the debate over whether to use this is settled. But FC is roaring back, and it’s more popular than ever. I definitely didn’t see this coming.

What do you hope this book will accomplish?

The book closes with a plea: Pretending away the impaired mind by insisting on this universal intact mind does tremendous harm to people like my son. So again, my goal with this book is really the same reason behind everything I write, to shine a light on the impaired mind. Severe intellectual disability is not shameful, but it does demand and deserve a great deal of support. We need to foreground the impaired mind in any conversation about disability and the types of services offered to this community.