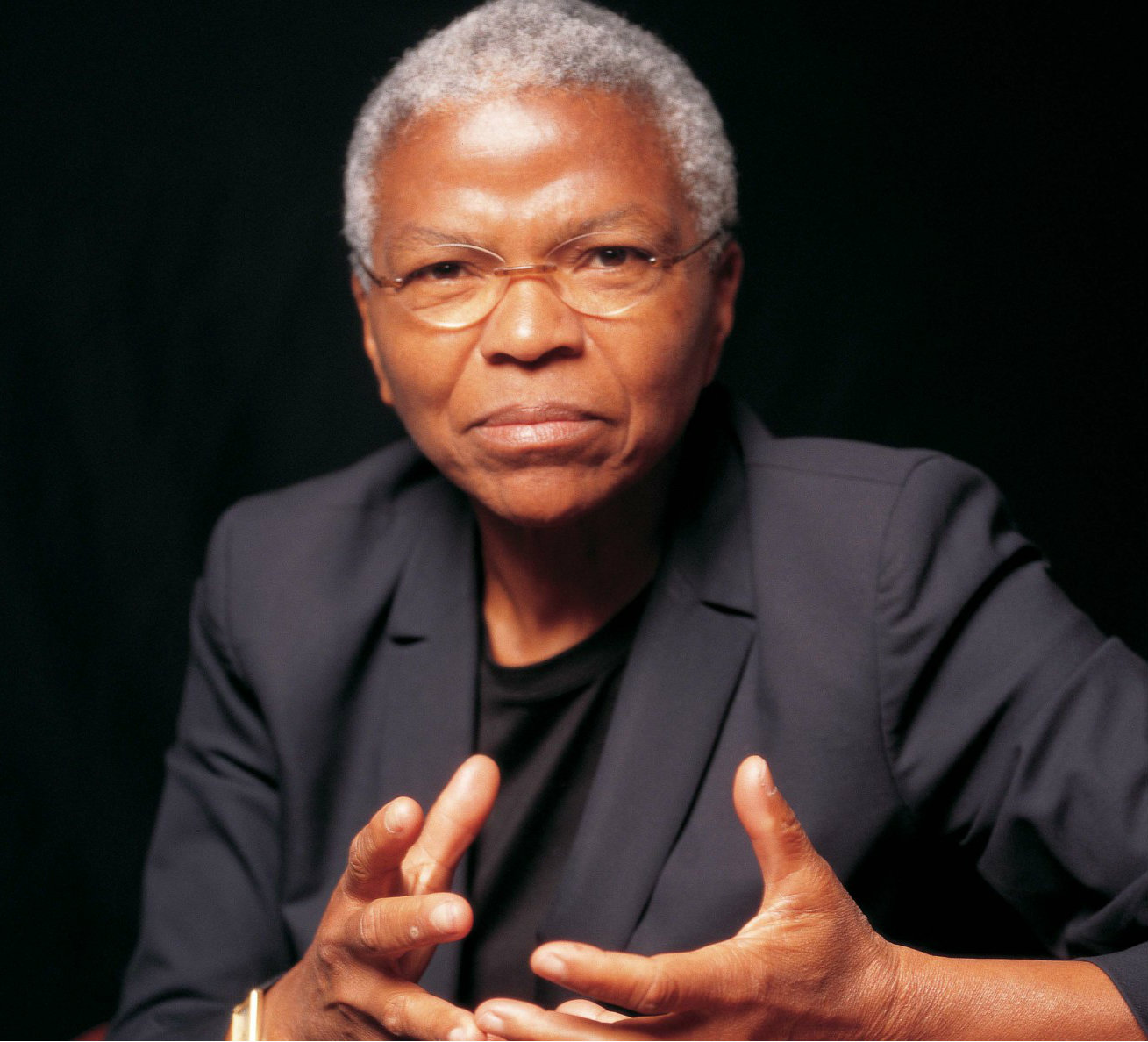

Mary Frances Berry, Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought and a professor of history and Africana studies

Thursday, September 7, 2017

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first civil rights legislation passed by Congress since the Reconstruction Acts following the Civil War. It created the Commission on Civil Rights and a dedicated Civil Rights Division in the Justice Department, and presaged later acts in the ‘60s.

We spoke to Mary Frances Berry, Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought and a professor of history and Africana studies, about this milestone act, where we are six decades later, and her thoughts on the white nationalist violence in Charlottesville, Va. Berry served for 24 years on the Commission on Civil Rights, the last 11 as its Chair. She has authored 12 books, most recently Five Dollars and a Pork Chop Sandwich: Vote Buying and the Corruption of Democracy.

How did the 1957 Civil Rights Act come about?

Mary Frances Berry: Newspapers were writing about lynching and other violations, and the Justice Department and the Attorney General would get letters from important people—important being wealthy—who wondered why the government wasn't doing anything. Newly independent African and Asian nations were also raising questions about the race policy of the United States. Their diplomats would stop to eat on the highway in Maryland driving between United Nations meetings in New York and Washington D.C., and sometimes they would be denied service. With the dispute between the U.S. and the Soviet Union for the minds and hearts of people in those new countries, the question arose as to what the great democracy really was.

What changes did the ’57 Act bring?

Before a formal Civil Rights Division was created in the Justice Department, when people wanted to complain to the federal government that some of their rights were violated, they would simply send something to the Justice Department or to Washington. I’ve seen letters addressed to “White House, Washington, D.C.” The letters would end up over at the Justice Department. Usually they would be turned down and the people would be told, “Go talk to your local sheriff.” Sometimes the local sheriff was the person who was violating their rights.

The Civil Rights Commission managed to carry out its responsibilities and held hearings, made recommendations. People who had credibility were put on it, like Father Ted Hesburgh, who was President of Notre Dame and widely respected. The Commission recommended the details of every piece of Civil Rights legislation that was passed all the way through the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The greatest challenge to the Commission came when Ronald Reagan decided to replace members even though he didn't have the authority. I was on the commission then and sued him successfully, but compromise was arrived at that keeps the Commission in jeopardy. Since that time, it's been very difficult for the Commission to play the role it's supposed to play. We spent years at a crisis point again, when administrations tried to appoint people to the commission who were hostile to Civil Rights. Now, because of the appointment cycle under the compromise, a temporary progressive majority of Commissioners are on board.

Where do we stand now in regard to Civil Rights?

We are in bad shape. On the one hand, we can all point to successful people of color and women and others. There's no doubt that things have improved, but there are some indicators that everyone should be aware of. The New York Times had a front-page story recently about how affirmative action has not benefited Blacks and Hispanics getting into the most prestigious universities. The gap in admissions is the same as it was 35 years ago.

The Times also ran an editorial last week about Black unemployment being twice as high as white unemployment. Then you have the issue of immigration, where the policy seems to have no rhyme or reason.

Episodes and incidents like Charlottesville happen that capture everyone's attention for a time and we see the disparities and how they affect people who are marginalized. The Charlottesville incident caused most thinking people to react in horror. Then they see that there are anti-fascists, they call themselves, on the left who engage in violence too. This seems to be undermining the non-violence of the protestors against racism and white supremacy, which has reared its head again. People say they’re surprised, but it has been there all the time.

What should we do to fight racism?

When Dylann Roof killed those worshippers in Mother Emmanuel Church in Charleston, I wrote an op-ed piece for the Washington Post which said it's okay to say take down the Confederate flag but that's a distraction if you don't do anything else, and too often we don't do anything else.

Now we have people talking about tearing down the Confederate monuments. I travel to New Orleans a lot. They just tore down all the monuments there. But in New Orleans you have a major crisis of Black youth unemployment and crime which politicians have not made remedying a priority. There is a major problem with education and the racial achievement gap in public schools remains.

I think on Confederate monuments, yes, you can take them down. However, I would prefer adding a statement to the monument describing the racist and sometimes treasonous behavior of the individual in question. Robert E. Lee, for, example, was a traitor to the United State. The statement should be inscribed in letters large enough not to be missed. I also would like monuments installed in the relevant states for slaves who were heroes and heroines—for example, Harriet Tubman and Gabriel Prosser and Denmark Vesey.

I am not persuaded by pious comments like: “I'm with you all the way. Yes, let's tear down that monument," when at the same time no improvement is made. We know what to do. One of my undergraduates asked me, "They keep saying they want to help poor kids—why don't they do what they do at the school I went to?" I asked the students if they knew why. After considerable discussion, they concluded it’s money. Those pious people are not willing to spend it. Instead they blame teachers or the students themselves or the parents or some elusive force.

If we were to pass a Civil Rights Act today, what should it include?

Most of what we need to do is to enforce the Civil Rights laws; that’s number one. Number two: We need to change Supreme Court justices so that we can get a different interpretation of the law. For example, the major problem with higher education is that when Bakke case was decided in 1978, the Court adopted something called diversity, which is what we all talk about all the time. We believe in diversity.

Diversity was the worst thing that ever happened to African Americans and, to a lesser extent, Latinos in higher education. Since that rule was announced, we have the numbers that the New York Times story reported. The gap has not decreased and that's because diversity has benefited a whole bunch of other people. To be sure it has benefited too few slave-descendant African Americans.

Affirmative Action, when it was first started by Martin Luther King and others, was a remedy for African American subordination and neglect. Diversity, while it appears to be a great thing for the few people who can get some of it, has not caused the kind of increase in admissions to the best places for African Americans.