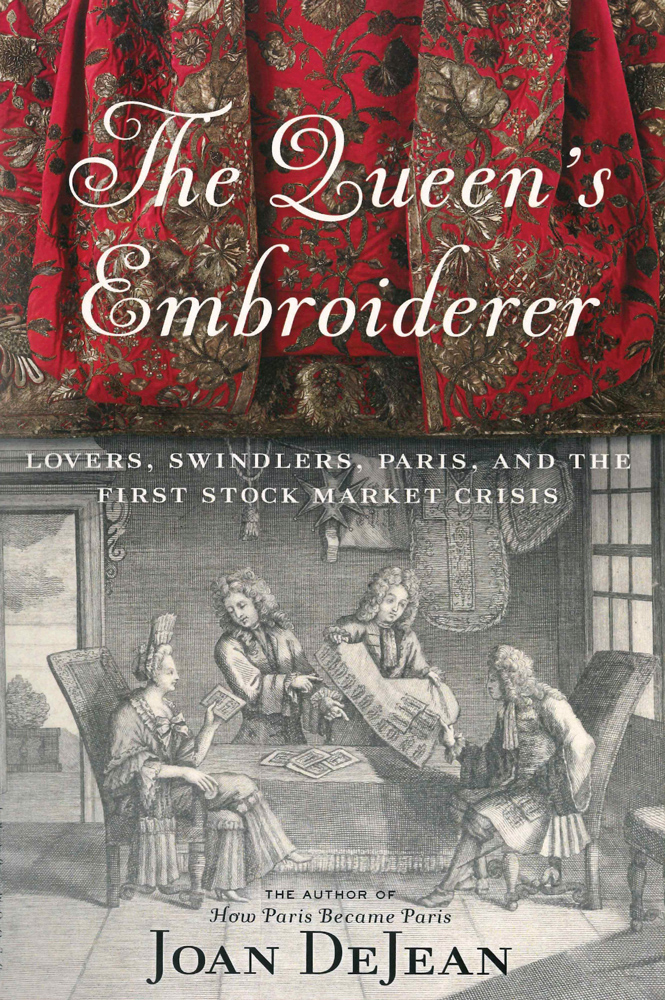

The Queen’s Embroiderer: Lovers, Swindlers, Paris, and the First Stock Market Crisis, the forthcoming book by Joan DeJean, Trustee Professor of French, has it all: star-crossed lovers, sumptuous artistry, scoundrels and family betrayal, greed and financial ruin.

It all started with an unexpected find. DeJean, who specializes in 17th- and 18th-century French literature and cultural history, was researching in France’s National Archives in Paris when she came across a document that left her stunned: a 1719 announcement that Jean Magoulet, officially known as embroiderer to Queen Marie-Thérèse, wife of Louis XIV, had accused his daughter Louise of prostitution. The announcement stated that she faced deportation to New Orleans.

“If you had seen the story of a father declaring his own daughter a prostitute in order to have her shipped off, you would have a hard time walking away, too, I think,” says DeJean. “I knew enough about Jean Magoulet to know that he wasn’t just an ordinary man. He was one of the city’s elite artisans.”

Magoulet was also a reckless spendthrift who was deeply in debt and eager to rid himself of his daughter, whose planned marriage would have enabled her to claim a percentage of her deceased mother’s estate.

Louise Magoulet’s predicament was tied to a madness gripping France known as the “Mississippi Bubble.” Decades of war under Louis XIV had left France nearly bankrupt. The monarchy turned to the economic theories of Scottish financier John Law. He proposed paying the national debt with revenues derived from opening up the Louisiana Territory to development. As head of the Indies Company, Law pushed the sale of company shares and advertised Louisiana and its newly founded city, New Orleans, as a paradise.

Under pressure to populate Louisiana with laborers, Law’s company offered free passage and land, as well as enticements for unmarried women to become “Louisiana brides.” To ensure enough white women, Law turned to strong-arm tactics, arranging to ship 150 female prisoners from Paris’s infamous Salpêtrière Prison to New Orleans. Unlike Louise Magoulet, these were mostly indigent women, immigrants, or others accused of prostitution or petty crimes. Jean Magoulet saw a chance to add his 17-year-old daughter to the ship’s manifest.

“This had never happened before,” says DeJean. “There was not a possibility of having your daughter sent away before. In this climate of huge risk-taking and huge gains, this becomes a phenomenon. Then, when the boom is over, the phenomenon of sending women away is over.”

The value of Law’s stock and the paper money he circulated as head of France’s Royal Bank inevitably fell, plunging the country into an economic crisis. DeJean’s research revealed the surprising effects of the boom and bust on ordinary citizens. “I had never thought about what it was like on the ground for individuals, for example, that the behavior of parents would be so closely tied to the fluctuations in the stock market,” she says.

Another surprise for DeJean was discovering that embroiderers were extremely well paid and enjoyed high status in the world of art. The Queen’s Embroiderer follows other fascinating threads and offers important takeaways for the present moment. The Magoulet story shows what can happen when people suddenly find themselves so driven by greed that they lose their moral compass.

“For me, that was a striking parallel,” says DeJean. Another has to do with the fate of the women marked for exile. “When you have no value for society, what chance do you have?” DeJean asks. “I think there’s a lesson for us about that, too.”