Preethi Kumaran, C’21

Wednesday, March 13, 2019

By James Prell

In the deep Pacific, intense heat combines with crushing pressures to create some of the most extreme conditions on the planet. Hidden from the light of the sun, life thrives here in the form of microorganisms that sustain themselves on a complex cocktail of chemicals exhaled by super-heated hydrothermal vents. Taken from these conditions without proper care, however, anaerobic microorganisms at these sites will die on contact with oxygen. Due to the extreme effort required for researchers to collect them—let alone isolate them in a lab—less than one percent of microorganisms found in these conditions have been described.

Preethi Kumaran, C’21, spent her summer break in a geomicrobiology Lab at Penn doing just that—and she just may have discovered something new.

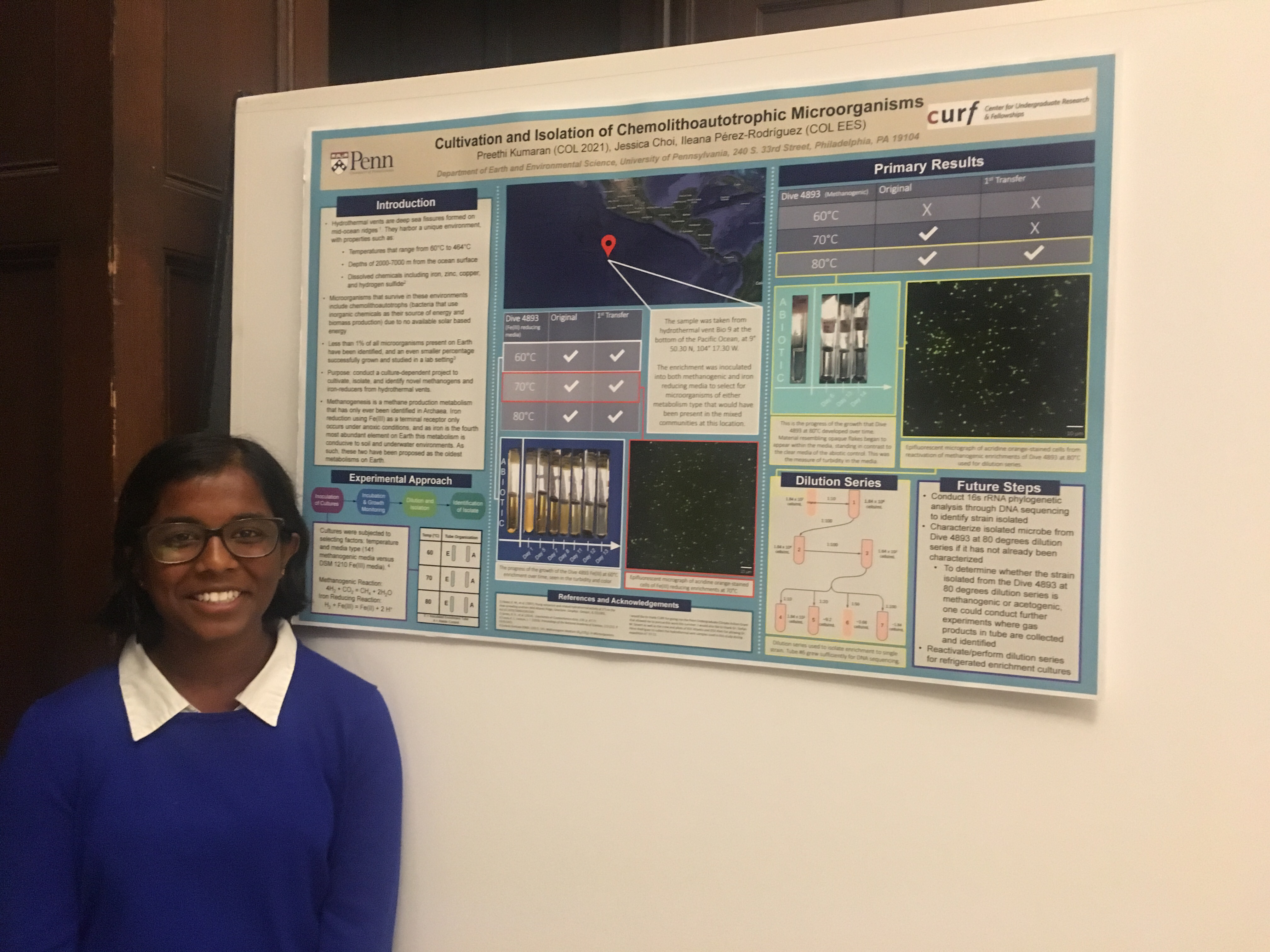

Kumaran was awarded the Penn Undergraduate Climate Action Grant by the Center for Undergraduate Research and Fellowships (CURF) to fund her work as a research assistant in Assistant Professor of Earth and Environmental Science Ileana Pérez-Rodríguez’s lab. Kumaran spent her days tucked away in the basement lab, staring at screens and monitoring gardens of test tubes.

The tubes contained samples that Pérez-Rodríguez, an Elliman Faculty Fellow, collected during deep-sea dives in the Pacific. Their goal? To identify microbes in these samples, add to the existing knowledge base—that one percent—-and, in some cases, identify further potential applications. Iron-reducing microorganisms, for example, could be used to decrease the toxicity of asbestos.

Day-to-day, Kumaran’s primary aim was to keep her test tubes of delicate microorganisms alive. “I was [testing them] under different reduction-oxidation and temperature conditions, trying to see if I could isolate microorganisms that we already have in the database or try to find something new,” says Kumaran. “It’s a really big world out there and there’s not a big chance that everyone has samples from the exact same spot, so there’s a likelihood of finding something new every time.”

Kumaran soon developed an eye for spotting compromised samples (a faint pinkish hue inside the test tubes signifies oxygen exposure, for example) and a deft hand with a syringe--hand-eye coordination is one of the “unexpected skills” that she developed in the lab, she jokes.

“There were so many trials. Months of trying different things at different conditions and finally one of them grew.”

After Kumaran successfully cultivated and isolated a sample that could be analyzed, the lab sent its DNA to be sequenced. According to their analysis, Kumaran’s sample from was a potentially novel deep-branching bacterial species.

Kumaran is cautiously optimistic, pointing out that “it’s possible that we found something new, but more work needs to be done to confirm it.”

Currently, others in Pérez-Rodríguez’s lab are working to see if they can recreate the results. Kumaran says it was a good opportunity to experience how the scientific process is carried out.