Senior Emily Belfer was casting about for a meaty topic for her honors thesis in history. She had completed the sequence of honors courses in junior year that prepares students to research and write a substantial, original paper. The subject matter should be something she cared about, she was told—something she would be eager to spend lots of time on.

“I played around with a lot of ideas,” recalls Belfer, a history major and English minor. The checklist of things she connected with included modern European history, pop culture and her Jewish upbringing. All of her grandparents had managed to survive the Holocaust. Two lived in Poland as non-Jews under false papers, one fled to Switzerland and then Italy, and the other survived the concentration camps. All of them lost grandparents, parents, siblings and most of their extended families. “My family has had a complicated cultural relationship to Germany that has lasted to the present,” she explains.

Drawing on her love of history, literature and popular culture—and the undercurrents of her family legacy—Belfer settled on a study of how Germans were seen through English eyes on the mainstream London stage during and between the two world wars: “Fighting Huns, the Enemy, and Jerry On-Stage: The Portrayal of Germans in the London Theater, 1914-1945.”

“During the First World War, there are a number of evil German-spy characters who are constantly trying to blow up the navy or slaughter a bunch of innocent people. They’re very caricatured.” – Emily Belfer

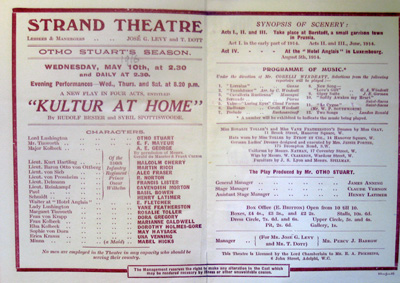

With guidance from Van Pelt Library’s reference staff, she first tracked down J. P. Wearing’s The London Stage, a catalog of performances on West End London stages between 1890 and 1959. She devised a metric to pick out the most popular plays of the period, which she then read, marking down references to Germans and the wars or noting how German characters were represented. “During the First World War, there are a number of evil German-spy characters who are constantly trying to blow up the navy or slaughter a bunch of innocent people,” she says. “They’re very caricatured.”

Belfer also culled through critical reviews of performances in The Times of London as well as more scholarly sources. “There were a few plays that were extremely popular in their day that seemed to be available only in London,” she says. So, with a Millstein Family College Alumni Society Undergraduate Research Grant, the young scholar traveled to London last summer. She found the hard-to-get plays at the British Library, but she also visited the Imperial War Museum and the Blythe House theater archive at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The plays she studied were commercially successful but largely B-level works, Belfer observes. “It’s crazy because some of them were performed for six years straight, but no one talks about these plays anymore.” Even the period works she examined by famous playwrights like J. B. Priestly are not taken as seriously as his other plays, she notes. “A lot of it is wartime propaganda or lighthearted entertainment.”

In her research, Belfer traces an arc of change in how Germans are seen by the English from cartoon villains during the First World War to a still negative but less prominent threat during the Second World War. In the interwar period, plays about the First World War dealt more with the struggle and pain of English soldiers in the trenches. Germans were notable more by their absence. “Even within the context of the World War II plays,” Belfer argues, “English problems at home are much more serious and much more worrisome than the German enemy.”

She attributes the shift to England’s decline as an imperial power during this period and the nation’s change of focus from the arrogance of colonial rule to anxiety over diminishing power and status as well as a preoccupation with the trauma of war. The world had changed as had England’s place in it, and the old rules no longer applied. Belfer characterizes English thinking in that period as, “What’s the point of harping on the past when the present is so much scarier?”

The research and writing “didn’t really feel like work,” Belfer confides. She particularly enjoyed doing history by studying popular plays rather than reading diplomatic notes and military reports surrounding important events. By studying popular culture—what she refers to as “how a population feels”—Belfer outlined “a bigger picture” than historical narrative typically captures in chronologies of dramatic events. “Even getting a snapshot of that,” she says, “is, to me, a lot more real and makes it much more relatable than studying decisions made by a small number of people.”