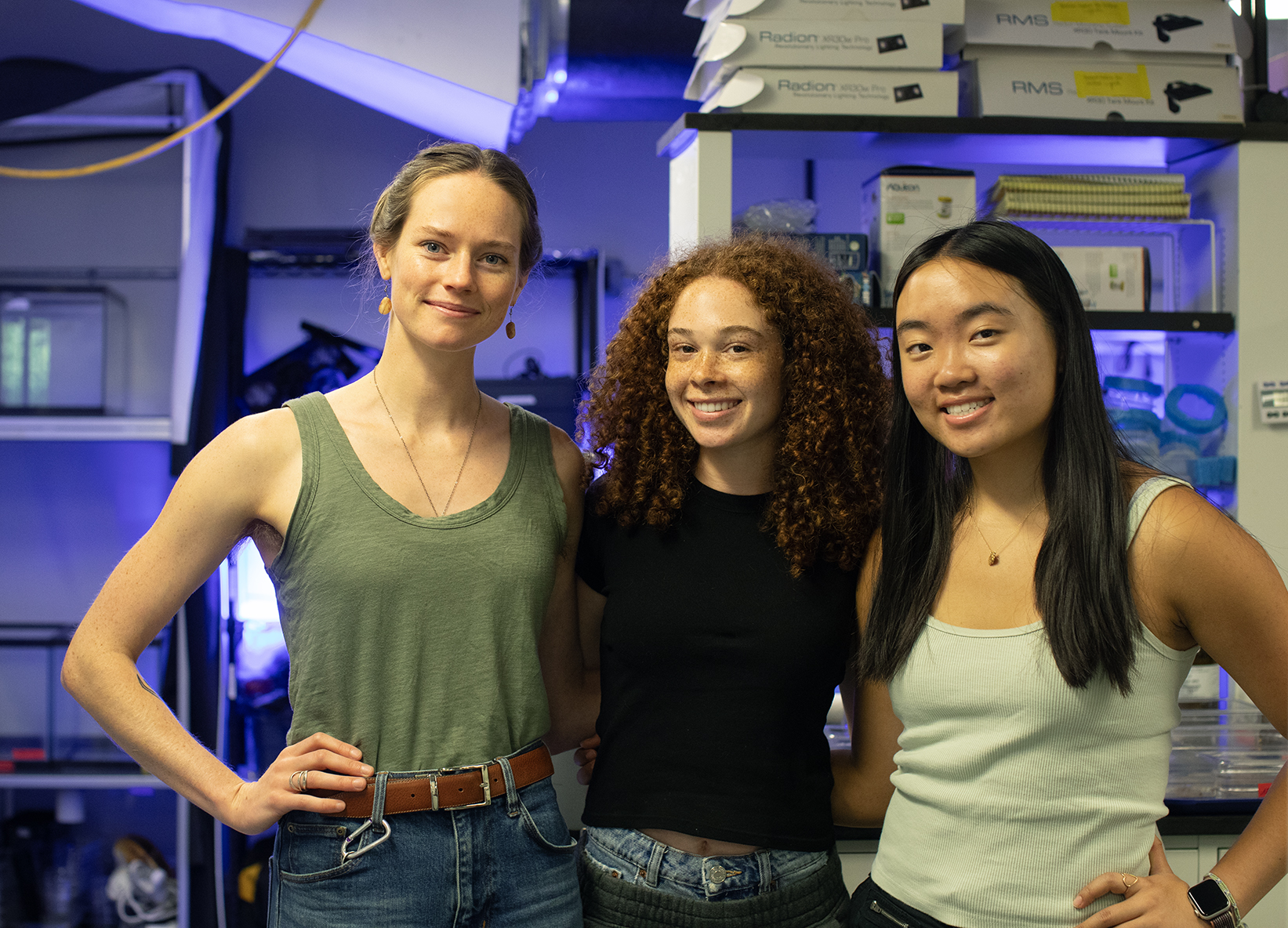

This summer, Luella Allen-Waller (left), a 6th-year Biology graduate student, has mentored Alex Piven (center) and Angela Ye during their time working in the Barott lab.

Tuesday, August 22, 2023

By Matt Gelb

Photos by Brooke Sietinsons

Alex Piven pulled a tiny vial from a bucket of ice and held it to a ceiling light on the third floor of Leidy Laboratories. Weeks earlier, specimens of a coral called Astrangia had been exposed to high-stress, warm temperatures, and now Piven was observing them on a regular basis. The process—tediously decalcifying the coral skeletons—is one way to analyze the effects of hotter temperatures on the coral’s tissue.

“You can actually see the little polyps,” Piven says. “This one still has some skeleton.” She grabbed a different coral sample and rotated it. “This one’s almost done. There’s no white. It’s mostly just the tissue.”

Seeing the changes was gratifying to Piven, a rising sophomore who knew she wanted to study biology but wasn’t sure what specifically interested her. She applied to Penn because of the abundant research opportunities. As she scanned the biology offerings from the Penn Undergraduate Research Mentoring (PURM) program offered by the Center for Undergraduate Research and Fellowships, the lab of Assistant Professor Katie Barott caught her attention. Barott’s research focuses on how climate change has distressed corals and reefs—across biological scales, from cells to whole organisms.

“I thought it was a really novel way to see how we can combat the effects of climate change,” Piven says.

That’s more pressing now than ever: July was the hottest month on record across the globe, according to the European Union climate monitor, and ocean temperatures reached new highs. About half of the Earth’s living corals have been lost, Barott says, a fact that threatens important ecosystems and coastal communities that need the reefs as a source of food and shoreline protection.

Piven and Angela Ye, another rising sophomore, have spent the summer conducting experiments to explore how resilient coral are when facing this kind of extreme environment change. Piven has been analyzing the cellular structure of a coral local to the Eastern seaboard, comparing corals with and without a history of heat stress. For her work, Ye turned to a model sea anemone used in this kind of coral research; she has been exposing the larvae to various high temperatures, then studying how this affects growth and development over early life stages.

Barott values having undergraduates—specifically recruiting first- and second-years—in her lab. She thinks it’s important to keep the next generation optimistic about the natural world. “With all the doom and gloom out there, people often shut down and lose hope,” Barott says. “But there’s still a lot of life left to save. There are many amazing reefs and habitats, both on land and in the ocean, to save. So, I like getting young people engaged in science and caring about the positive change we can still make in the world. Not all hope is lost. It’s dire. You can’t lie about that. But it’s important to have a sense of hope.”

For the two undergrads, this summer has represented a gateway into those studies. Piven had done research for a summer in high school and Ye never had before; through PURM, they had a chance to learn about themselves and the ways Penn biologists are thinking about the future.

“I found myself getting really frustrated with people just talking about climate change and not doing anything about it,” Ye says. “I want to contribute ultimately in a way where I can actually take action on the issue. So however small my work is, it gives me a lot of purpose. It opens up my eyes to the things we can do.”

Back in the basement lab at Leidy, Ye tends to tiny sea anemone larvae exposed to various high-stress temperatures for about an hour soon after they were born. This specific anemone, Nematostella, is a model organism closely related to corals. As Ye feeds them shrimp particles, she can already see differences in the larvae exposed to the most heat. One group, subjected to 39 degrees Celsius (102 degrees Fahrenheit), is significantly smaller than the others. But even though they had lower heat tolerance, those larvae expressed more of a certain heat shock protein. They were adapting, Ye says.

“Most corals spawn in the summer months,” Barott says. “So one question that we’re interested in is if these new coral larvae—the babies that are the next generation of adults on the reef—if they see hot temperatures when they’re really young, could that actually prime them to perform better under heat stress in higher temperatures as adults? Is there some benefit to having that high-temperature exposure early in life? It could reprogram some of their development and gene expression patterns that might carry through and hopefully boost their performance in the future.”

Ye and Piven lived on the same floor during their first year at Penn, but they were not friends. The experience of spending many hours together in Barott’s lab this summer has drawn them closer. “I’m grateful that Penn has the opportunity for us to do that,” Piven says. “It’s even more unusual to get placed in a lab in a research university and to be paid as an undergrad—especially coming out of freshman year.”

Barott says what separates her lab’s work is a specific concentration on the cell biology and symbiosis inside the coral. Her team does research in Hawai’i that includes following individual corals for almost a decade, seeking to understand what makes some individuals resilient and others sensitive to the repeated heatwaves these corals have undergone. The summer experiments that Ye and Piven conducted are on a much smaller scale, but Luella Allen-Waller, a sixth-year graduate student in Barott’s lab, sees great benefits to having the undergraduates there for the summer, for the students and the lab.

Both students were detail-oriented and asked probing questions, “which is an especially useful tool for those of us who have been sitting in these ideas for years,” Allen-Waller says. “It’s a beautiful and unique biological system, but you can still sort of get used to it. You can take for granted the things that we assume about our organisms.”

Having curious new minds in the lab forces everyone to think about the questions in a different way, she adds. “[We] sort of go back to the root and ask, ‘Are we really asking the right things? Is this what matters the most?’ Even just something as granular as why we do an experiment a certain way. Having that fresh perspective is priceless.”

And it’s helped both students narrow their focus.

“I definitely want to take a marine bio course now,” Ye says.

“Yeah, me too,” Piven agrees. “I was open to it going either way: Maybe this experience will show me I’m not interested, but I’m glad it led me in the direction that I am.”

Allen-Waller nods. “Which,” she says, “is a massive victory for us.” And for the coral the lab is working to protect, too.