Every culture has its own origin story—its texts, its heroes and its beliefs. But in a relatively new country like America, how does any one culture stake their claim to an "American" history? It's a question that fascinates Professor of History Beth Wenger, as it pertains to Jewish Americans.

Over the course of her career, Wenger has made an effort to examine periods of American Jewish history that have received less attention. Her first book, New York Jews and the Great Depression: Uncertain Promise, chronicles the Jewish experience during a period of doubt.

"When people hear that I wrote a book about the Great Depression, they always think I am an economic historian," she laughs. "But I was primarily interested in this particular historical moment. The 1930s marked the first time since mass migration that the American Jewish population became primarily American-born. The Depression struck just as American Jews were making the transition between an immigrant culture and the well-integrated, highly acculturated Jewish community that emerged after World War II."

Most immigrant Jews had come to the United States hoping for better, more secure lives for themselves and their children, and by the close of the 1920s, those expectations seemed within reach. But the economic crisis, the insolvency of communal institutions and synagogues—coupled with the rise of anti-Semitism at home and abroad—shook the confidence of American Jews.

"The stories that Jews told date back to Columbus. One popular Jewish history textbook chronicled the often repeated story about the Jewish interpreter who sailed with Columbus, claiming that he was actually the first one off the boat, so that a Jew was the first to set foot in the New World." – Beth Wenger

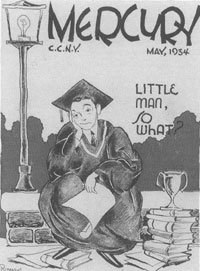

"There's a great cartoon from a City College humor magazine in 1934 that shows a college graduate dressed in his cap and gown, holding his diploma, with his head in his hands and the caption reads, 'Little man, so what?' The image perfectly captures the mood of young Jews in the Depression. It's this moment in American Jewish history when Jews harbored grave doubts about their future in America that really interested me."

For the most part though, Wenger explains, the United States has been a place that Jews regarded as "home." To this end, Professor Wenger has taken on projects that deal heavily in primary sources. One notable example of this is her work on The Jewish Americans, a critically acclaimed six-hour PBS documentary for which she served as an expert advisor. She also authored an award-winning companion guide to the series, titled The Jewish Americans: Three Centuries of Jewish Voices in America, that introduces readers to primary sources in a highly readable and accessible fashion.

"The guide includes a letter that one woman wrote in the 1790s to her parents in Germany. She's living in a small town in Virginia. She claims she can't lead a real Jewish life there because of the lack of synagogues and the absence of any semblance of a Jewish community," Wenger says. "Another account belongs to a Jewish Civil War soldier. He details how he and his fellow Jewish troops managed to celebrate Passover at the front by finding creative substitutes for the ritual foods traditionally required for a Seder. There's even an account from the founders of Macy's that traces their roots as peddlers and petty traders. I really tried to capture a kaleidoscope of Jewish voices and experiences, from the well-known to unknown, from politicians, actors and activists, to peddlers and sweatshop workers."

Wenger's interest in public history has continued. She is one of a team of four historians who helped to craft the exhibition at the newly opened National Museum of American Jewish History on Independence Mall.

Her work in public history helped prepare Wenger for her latest book, History Lessons: The Creation of American Jewish Heritage, which explores the ways that American Jews invented a history of their own on American soil.

No legitimately professional field of American Jewish history existed until after World War II, so Jews, like other immigrants in America, crafted a history and heritage of their own. To uncover this history, Wenger mined all sorts of unusual sources, from national holiday celebrations, to public commemorations, to monument projects, to the retelling of American Jewish history in children's literature and textbooks.

"The stories that Jews told date back to Columbus. One popular Jewish history textbook chronicled the often repeated story about the Jewish interpreter who sailed with Columbus, claiming that he was actually the first one off the boat, so that a Jew was the first to set foot in the New World, and that this same interpreter in fact named the turkey, calling it tukki, which is the Hebrew term for peacock. If you pick up texts produced by other ethnic groups in America, you'll find the same sort of thing, as all minority groups worked to create an American history of their own."

American Jews also actively promoted their own heroes, such as Haym Salomon. Salomon was a revolutionary patriot, known also as the "financier of the revolution." He was a broker who helped secure loans that supported the troops in the revolutionary army, Wenger says. But while he did perform valuable services for the nation, his exploits were also exaggerated in many accounts. There were fierce battles within the Jewish community during the 1920s and 1930s about building a monument to him in New York and the effort ultimately failed, but there are statues of him erected in Chicago and Los Angeles.

In addition to her published works, Wenger co-curated Holy Land: Place, Past, and Future in American Jewish Culture, an exhibit that gathered texts and images of Palestine in the century before statehood and highlighted how both Jews and non-Jews grew closer to this place through tourism, consumerism and the popularization of archeology.

Wenger is interested in dealing with issues of Jewish masculinity in the future. She is considering work on a book that would explore the transformations of Jewish manhood in the United States, a subject that has been examined in European Jewish history but much less frequently in an American context.