Religious texts are often deemed timeless, but as the King James Bible celebrates its 400th anniversary this year, we are reminded that they are products of history as well. In 1604, James I approved a proposal by Puritans to authorize this translation of the Bible, declaring that he "could never yet see a Bible well translated in English." One of the English versions in use at the time was the Bishops' Bible, authorized by James I's predecessor, Elizabeth, and—posits senior Valeria Tsygankova—itself a political calculation by the Elizabethan state.

Funded by grants from Penn's Center for Undergraduate Research and Fellowships, the Benjamin Franklin Scholars program and the Penn Humanities Forum, Tsygankova is writing her senior thesis on what the paratexts of the Bishops' Bible—its title pages, reader guides, ornaments, marginal annotations and initials that surround the biblical text—reveal about the relationship between religion and the state in Elizabethan England. The English major first became motivated to examine books as physical objects during her sophomore year in a course she took on the history of the book taught by Peter Stallybrass, Walter H. and Leonore C. Annenberg Professor in the Humanities and Professor of English and of Comparative Literature and Literary Theory.

"Instead of looking at texts as just an abstract container for an idea," Tsygankova says, "I became fascinated by the idea that you can also look at them as physical artifacts. You can explore their form and history to learn the meaning behind the text and the culture that produced it."

Tsygankova's interest in material texts was further fueled by her work developing online exhibits and finding aids for materials in Penn's Rare Book and Manuscript Library, as well as the book-making classes she has taken in the Department of Fine Arts in Penn's School of Design. In one, she wrote and constructed a book-length poem, choosing its binding, paper and structure. "This exercise really allowed me to play around with the idea of how the body of the book might contribute to how a reader interacts with it and takes meaning away from it," Tsygankova says.

"Instead of looking at texts as just an abstract container for an idea, I became fascinated by the idea that you can also look at them as physical artifacts. You can explore their form and history to learn the meaning behind the text and the culture that produced it."

– Valeria Tsygankova

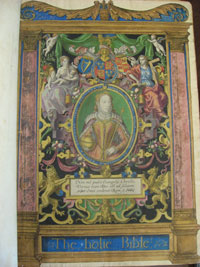

She discovered the Bishops' Bible in Stallybrass' class and was struck by its title page, in which an ornate, engraved portrait of Queen Elizabeth occupies the space where the title and publisher information usually would have been. Only at the base of the portico framing this image can one read, "the holie Bible." Inside, more portraits of the aristocracy can be found—engravings of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, preceding the Book of Joshua and of William Cecil at the start of the Psalter—and throughout are markers of those involved in creating the translation, such as the initials of Archbishop Matthew Parker. In places where the book gives information about itself, Tsygankova explains, the paratext content is not biblical, but rather "stages the presence of a 'godly monarchy.' "

Tsygankova argues that the overwhelming prominence of the state in the Bishops' Bible's paratext points to the state's attempt to balance accessibility and authority in matters of religion. The first printed English translation of the Bible had appeared only a few decades earlier, and it was considered so radical that its creator, William Tyndale, was executed at the hands of the Catholic Church. But by the time Parker's bishops began work on the Bishops' Bible, one authorized version, the Great Bible, had already been produced under Henry VIII, and the unauthorized Geneva Bible was popular in many homes. The latter, a small and simple publication, was radically Calvinist with an anti-authoritarian bent.

The Bishops' Bible, Tsygankova explains, had the goal of replacing both the Great Bible and the Geneva Bible with a book that would stand for Elizabeth's fledgling reign. Although it was heavily influenced by Tyndale's work, it bound his revolutionary translation with paratext that strongly evoked the authoritative presence of the church and of the monarchy.

"The costly engraved portraits and the fact that it was printed in very large versions meant that it could only be displayed in church settings and in the homes of bishops and priests who could afford it," Tsygankova says. "It was in the vernacular, but people were only supposed to look at the text in controlled spaces dominated by hierarchies."

Tsygankova credits her education at Penn for pushing her to "examine the texts of the canon to look at where they came from, how they came together, and how they became part of the canon." As a 2011 Thouron Award recipient (a graduate exchange program between British universities and Penn), she will continue this work post-graduation in a master's program in the history of the book at the University of London's Institute of English Studies. Tsygankova is also the recipient of a Beinecke Scholarship, which she is planning to apply toward pursuing a Ph.D. in subjects that bridge her interests in material texts and contemporary poetry.