The term “bureaucracy” has become synonymous with an overadherence to rules and structure—red tape. But, over time, John DiIulio Jr. says, America’s aversion to a well-trained, governmental workforce has come back to bite it. In his new book, Bring Back the Bureaucrats: Why More Federal Workers Will Lead to Better (and Smaller!) Government, he seeks to expose a federal government too dependent on proxy-administration. DiIulio, the director of Penn’s Robert A. Fox Leadership Program and the Program for Research on Religion and Urban Civil Society (PRRUCS), also served as the first director of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. He has received many prestigious honors, including the 2010 Ira Abrams Memorial Award and the 2010 Lindback Award for Distinguished Teaching.

Below, the Frederic Fox Leadership Professor of Politics, Religion, and Civil Society, provides his diagnosis of the American government, and discusses steps to recovery.

How did the book come about?

What really motivated me was I wanted to have an answer for my students when they asked me, “What do you really think about these issues?” I’ve been teaching Introduction to American Politics and Government for most of my 34 years as a professor, and what I've found with this next generation of students is that it's really the time after lectures that is most important. I used to be famous for hosting these Talking Turkey lunches, where I'd sit in Philly Diner for 10 hours and anybody could come in. And what happened over the years was that instead of asking me questions about course material, what the students really wanted to know is, what do you think about it? You know: you worked in the White House, you were at the Brookings Institution, and you take all these different positions on different issues, so tell us your opinion. And this book was the perfect opportunity.

In the book you use the term “Leviathan by proxy" to describe the current state of governing. What do you mean by that?

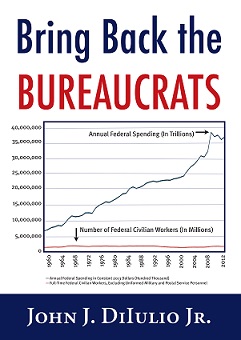

It boils down to two simple things: the American government is debt-financed, and it is proxy-administered. If you know those two facts, you know more than someone who knows everything else about the current American government. The federal workforce hasn’t increased since the 1960s, while the budget has only grown, which means the government is paying other people to administer its own services. And the enemy is, in effect, us—the American public. We have elected incumbents to Congress for 50 years, in both parties, who have given us—We the People—what we demand, which is essentially that we want government benefits, but prefer not to pay for them with higher taxes, and we prefer not to have big bureaucracies.

And so what we have is essentially a way for Congress to use any instrumentality it can get its hands on to administer federal policies without having to count them on the federal payroll. It’s fundamentally dishonest. It’s the antithesis of democratic accountability, and it’s an institutionalized form of pandering. The military has 800,000 defense employees, but 700,000 for-profit contractors. These are companies that have had violation after violation, nonperformance after nonperformance, and continue to get contracts.

In addition to the federal by proxy system, you cite two other offenders: state by proxy and nonprofit by proxy. How do these figure in?

At the same time that the federal workforce has remained flat, the state and local government workforce has more than tripled. And a lot of those people who’ve been hired at the state and local level have been hired with federal funds, and function as de facto federal government employees. The lobbying is obvious when it’s a defense contractor, but when you take bodies like the National Governors Association, the U.S. Conference of Mayors, the National Association of Chiefs of Police, all of which essentially function as lobbies, what they want is always going to be more money with fewer strings. So it’s not that it’s an inherently bad thing…. [M]y wife, who’s a former assistant director of Medicaid for New Jersey for several years, was a de facto federal employee. I like my wife. I think she did a good job [laughing]. It's simply a corruption. It's a system that basically has people who are in a position to keep programs going, whether they’re successful or effective or not.

And then, last but not least, you have the nonprofit folks. My mother was in St. Francis Nursing Home. It’s a nonprofit Catholic nursing home, but it’s really a Medicaid administration facility, as are virtually all the nursing homes in America. Once again, you’ve put people in a position where the administrative apparatus also functions as a lobby. Now, there’s nothing inherently wrong with lobby and interest groups, but no one’s asking the question, what’s in the public interest? Is this a good program? Everybody has a little bit too much of a tangible stake.

You cite FEMA's problems during Hurricane Katrina as an example of how this “by proxy” system has negatively affected governmental departments. What are some other examples?

FEMA is only one example. It was starved for staff. It wasn’t allowed to hire and staff up full-time federal employees. And by the time Katrina hit, it was down to its lowest staff level in more than a decade. It couldn’t have responded effectively if it was well led, which it was not. So you could blame Mr. [Michael D.] Brown, but he was not the problem. Mr. Brown was just maybe a symptom of another problem, which is using political appointees to run government agencies in a way that doesn't make any sense. … And you have other conflicts of interest, like when the Affordable Care Act health exchanges were launched. A lot of the groups that ended up getting contracts were groups that, if you follow the money and follow the breadcrumbs, were lobbying [for] the bill.

Some argue that federal government doesn't have the expertise to run some of these programs but there are a lot of examples of federal government that works. People don’t think of bodies like the U.S. Forest Service. This is a department that has got several millions miles of roads to deal with. People don't like the IRS because of corruption over the years. But the fact of the matter is you don’t have enough agents to look after a nonprofit sector that has tripled in size over the last 25 years. The bureaucracy is always easy to scapegoat, but often, if they had the additional resources or even just training, these could be successful programs.

Can a balance be struck? What needs to change moving forward?

We must decrease our reliance on proxies and increase the federal workforce. I say in the book that eliminating the entire full-time federal workforce would save less than the government spends on Medicare, less than they spend on defense contractors. Something is wrong there. Does that mean we should have no contracting? Of course not. Does it mean we shouldn’t rely on some degree of outsourcing? Of course we should. But we should do it in a way that asks the fundamental question, how do we make government work better and cost less? And what kinds of public, private, and other partnerships and contracts and grants, monitored how, measured how, would be most efficacious and most in the public interest? And what size, what composition of a government full-time workforce do we need to make that work better and cost less? The answer’s got to be north of what we have now, both in terms of the number and in terms of the character and quality of the training.