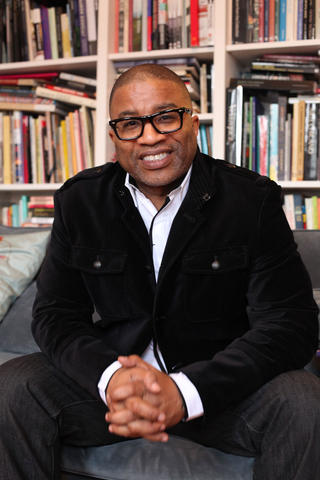

Music biopic Straight Outta Compton, the story of pioneering hip-hop group N.W.A’s genesis in Los Angeles, opened to critical acclaim this past August, nabbing the number one spot at the box office its first weekend. It has gone on to become the highest grossing music biopic of all time. We sat down with the Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Music Guthrie Ramsey, Jr., musician, author, and editor of the Musiqology.com blog, to examine the film’s cultural significance.

Blake Cole: How significant is N.W.A to the hip-hop genre and to music in general?

Guthrie Ramsey: They are representative of a generation of young musicians who grew up with a different music-making model available to them, one that differed radically from their parents’ generation. I don’t know whether any generation of people in the 20th century can claim that—that the musical world that they inherited was radically different in such fundamental ways than the music-making of their parents’ generation. So I just saw them as being emblematic of what could be achieved during the hip-hop era of music-making.

BC: The group had multiple disputes with its music label. What did it mean for the industry for burgeoning stars like Dr. Dre to break off and form independent ventures?

GR: Well, I think it was radical. Of course there were precedents like Ray Charles and James Brown in rhythm-and-blues, who kind of made the rules up for themselves as they went along. But with N.W.A members, they were not beholden to the same rules, in terms of the musician’s relationship to the music industry and the business entities that previous musicians were. So it just seemed like kind of from the late ‘80s on it became kind of a Wild Wild West. And then when the digital revolution really took hold it really became like the preamble, and now it’s sort of all bets are off—you’re in business for yourself.

BC: Do you think members Ice Cube and Dr. Dre helped to pave the way for the current generation of musician-entrepreneurs?

GR: Yeah. But, you know, look at Elvis Presley. He started out as a rock-and-roller, and then five years later he’s playing roles in movies that were meant for general consumption. And then he wound up in Las Vegas. So I think that is the paradigm of the rock-and-roll and hip hop artist, to move from the margins to the center, and then become power from within the industry.

BC: N.W.A is famous for its raw lyricism that often tackles subjects like police violence against minorities. What kind of impact has the group had on free speech, censorship, and social reform?

GR: I think context has a lot to do with how powerfully we experienced it. It wasn’t made in a vacuum. It was all part of a larger kind of sense of unrest in the sociopolitical lives of Americans brought on by Reaganomics and other larger instances of inequality. So if you start making songs like that at a particular moment, it’s going to have a kind of resonance. And as we see now, people are still claiming that for themselves. What I find most interesting, however, is that this idea of questioning or speaking back to authority is only one of the ways that everybody gets their underwear in a bunch about things in hip-hop, because sex has been as equally provocative in this case. So you have questioning political authority, and then you have the themes and topics of sex in songs, which is also kind of forbidden territory. It was only one of the ways hip-hop began to be a subversive wing of pop music culture like rock n roll.

BC: What about detractors who say N.W.A’s lyrics encourage violence?

GR: I think the violence that was both reported and supposedly reported in hip-hop lyrics, is a very complicated matter because, if you go to Hollywood films, there’s a certain amount of violence that one is accustomed to and in fact expects from these films. And no one accuses Tom Cruise or 007, as fictional protagonists, of creating violence or encouraging violence. There’s something about the protagonist in popular songs, particularly when young black people are performing them, that real life experience and artistic invention get collapsed and seem more dangerous than it would be, say, in a horror film or whatever.

So, I think that’s specific to pop songs and popular culture in general. For instance, no one goes to a soap opera actress and believes that they’re breaking up marriages in their real life. And also the perception of the larger culture is that these people are violent anyway, so they must be singing about who they believe they are in the world. So it’s very complicated. You almost have to go song by song, artist by artist, to get to the bottom of what’s going on, what culture transaction is going on between the musical object and the listening audience.

BC: The film comes at a particularly poignant time given that police-community relations are tumultuous in many cities across the U.S. due to incidents of violence. Do you think the film provides an opportunity for new discourse?

GR: I think there are two historical things going on. Number one, you have a group of black men talking about how they experience their lives in relationship to a militarized police force in their neighborhood. And what they did in fact for their listening audience is to open up how they experienced life in ways that people no longer are paying attention to. It’s sort of like what happened with the earliest generation of civil rights photojournalism and the idea that, when television cameras were trained on these cops with water hoses against protestors, it showed the world what was really going on. And in a way, that is the same thing that N.W.A did, to a certain extent, with some of the things that they were experiencing.

Now, you move forward, to the invention of the cell phone camera. We’re at another historical moment where people are actually being able to witness what people claim has been going on forever. So now you have documented evidence of it. And it’s being greeted as news by the larger American public, but the people who have been subjected to that, they’ve known about it all along. I look at those three historical moments as linked: the photojournalism of the ‘60s; the moment where hip-hop artists began to document through their art what they were experiencing; and then this new moment of visual and recorded evidence of what people are experiencing. Straight Outta Compton is doing similar cultural work that the film Selma did last summer. And that is to bring attention to an historical moment, and then we get to see how congruent it is with what’s going on in the present.

BC: The film’s accuracy has been criticized by some, particularly the omission of purported acts of violence committed by group members—especially given that some of them are producers. Do you think it’s problematic for musicians to take such a prominent role in their own biopic?

GR: Truth be told, if we get to tell our own story, we want to look a certain way. That’s what memoir is—it’s a sketch. So in order for it to actually be accurate, if that’s ever even possible, you would need other perspectives. But I don’t think anybody should be surprised that the way they wanted everybody to understand their lives was as extremely creative and extremely randy young men.

We’re in a moment now where violence against women is being spoken out about in more public ways than it ever has. But why would anyone jeopardize their box office by including the truth of these women? It doesn’t make good business sense. And if anything, we know that these guys are really great businessmen. And so Hollywood films in general never promise us truth, they promise us entertainment.

BC: Compton boasts a new generation of hip-hop superstars and critical darlings like Kendrick Lamar, who cite N.W.A as their biggest influence. Has the dynamic changed in how artists today communicate with their fans?

GR: People keep building on art forms, and they learn from previous generations, and they try to advance it. If anything, I think that with someone like a Kendrick Lamar is that he seems to have rejected this burden of didacticism that some rappers embrace. But he can actually do more abstract, more indirect addressing of issues through his art than they did in the young art form that NWA was participating in the late ‘80s. In fact, we would be bored if people kept reproducing the same thing. So it’s really a lot of pressure for young artists to keep pushing it ahead.

“Straight Outta Compton”: Documenting Through Song

Guthrie Ramsey, Jr., Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Music, discusses music biopic "Straight Outta Compton."

Monday, September 21, 2015

By Blake Cole